Trump in Chains It is well posed, one must give the devil credit: defiance shouts, frozen in fury, at the top of grievance, as petulant as it is silent; the furious eye, triumphant in mockery, disdains the camera and, through its harsh lens, you. But there is no gratification. A dull ache, sequela from a blow, taken long ago, swells in the soul of even the most opposed when faced with this humiliation. No: no gratification, only sorrow at this portrait of the folly of mankind at war with itself, nature, and the gods, taken in the bowels of a southern jail. There, but for the grace of the devil, go I. Christopher Bernard's collection The Socialist's Garden of Verses won a PEN Oakland Josephine Miles Award and was named one of the "Top 100 Indie Books of 2021" by Kirkus Reviews. His two books "for children and their adults," If You Ride a Crooked Trolley . . . and The Judgment of Biestia, the first in the series Otherwise - will be published in November 2023.

Category Archives: BERNARD

Poetry from Christopher Bernard

Whose Body It’s half past July. The trunk of the backyard tree lies beneath your hand. A smell of moss crosses the yellow wood. It was the wind broke it, the wind in the night. See the ladybug. She works her way up the bare stump like a tiny VW, anxious for her children in the burning house. A worm pokes a blind head above the cracked ground. The ferns pretend to be asleep. Beyond the fence, the willows are grave in stillness. The sun blinds the eastern arc of the sky. It holds its breath. Even the stone beneath your knee. Then it crosses the silence on great wings toward the future. _____ Christopher Bernard is a novelist, poet, critic and essayist. His poetry collection The Socialist’s Garden of Verses won a PEN Oakland Josephine Miles Award in 2021. He is also a founder and co-editor of the webzine Caveat Lector. His children’s books If You Ride a Crooked Trolley . . . and The Judgment of Biestia will be published this fall and featured in Kirkus Reviews in November.

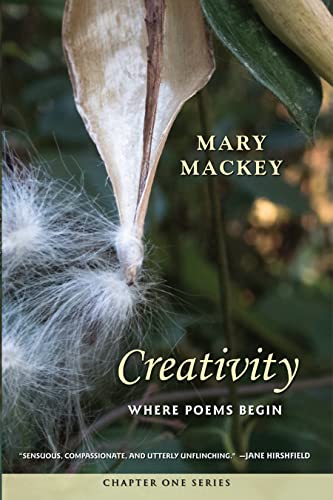

Christopher Bernard reviews Mary Mackey’s book Creativity: Where Poems Begin

The Search for the Source

Creativity:

Where Poems Begin

By Mary Mackey

Marsh Hawk Press

The greatly talented Mary Mackey’s slim but profound and beautifully written book has a slightly disingenuous title. If you are expecting a scholarly exploration of the creative mind such as you will find in Arthur Koestler’s classic work The Act of Creation or Silvano Arieti’s Creativity: The Magic Synthesis, you may be disappointed. Or if you expect something like those works but focused on literary creativity, you may also be.

But what you will get is just as worthwhile. I can see why Mackey did not call her book “My Creativity: Where My Poems Begin,” because, though no sufferer from imposter syndrome, she is too courteous toward her reader to thrust her ego unapologetically into the foreground. Even the most brilliant writer realizes that the world does not revolve entirely around her. But the revised title is an exact description of what we find in these pages.

That Mary Mackey is not better known is a bit of a scandal, because we are in need of her eloquence and originality. But I have long given up on the taste of the public and many of its would-be literary critics – eloquence and originality have been replaced by vulgarity and imitativeness (and aesthetics has long been replaced by politics) as the keys to success in contemporary America, may the gods and the Muses forgive all of us.

Unhappily, even posterity cannot be entirely depended on to have taste, intelligence or judgment. If Darwin rules, we can hardly expect natural selection to be wiser or kinder than we have been. And contemporary culture is beginning to look more and more Darwinian with each passing season. In the meantime, a few lucky readers will benefit from her books. And this is one of the gems among them, and is likely to ignite interest in her other books.

What, after all, is this nebulous thing we call “creativity”? Every time we speak we are engaging in a creative act, as the linguist Noam Chomsky regularly points out. We invent an original response to every event that happens to us – every moment is fresh, novel, unrepeatable, however boringly familiar it might seem to our half-asleep minds and benumbed senses. Every night, every dreamer creates a new universe.

But there is a hierarchy in creativity: though there is clearly a relationship between them, there is also a qualitative difference between this kind of creativity, shared by all sentient beings, and the creative leaps that result in the discovery of relativity, the painting of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, writing Ulysses, or composing Bob Dylan’s anthems from the ‘60s.

Or writing a book like Mary Mackey’s prize-winning poetry collection The Jaguars That Prowl Our Dreams or her other collections (which include Skin Deep, Sugar Zone, and Travelers With No Ticket Home) and her densely poetic novels such as Immersion, A Grand Passion, and The Valley of Bones.

There is another difference: most successful artists, grateful for their creativity, or merely taking it for granted (and perhaps afraid to look too searchingly into a gift horse’s mouth for fear the horse will bolt at reason’s first cool poke), they revel in its fruits but don’t make a quest to discover its sources. Mackey is not satisfied merely to enjoy her gift; she has decided to try to find out where it comes from, what causes it, how she has become to be so graced.

And the result is this memoir of her creativity.

It has often been said that the most valuable gifts often come in small packages, and many a short book holds more substance than a far weightier tome. The saying surely applies here.

To say that Mackey has found the ultimate source of her phenomenal gift – the source of the Nile, the Higgs boson that transforms chaos into resplendent form – might be going too far, but to say she has come as close as it might be possible to go is, I think, not claiming too much.

Her book is divided into thirteen short chapters, most of them concentrating on moments in her life when she became most aware of the assertively creative currents within her as they broke into consciousness. These include experiences of intoxicating fantasy during the extreme fevers Mackey has had since she was an infant; experiences that drove her mind into visions and ecstasies that became key to how she engages layers of the mind (“preverbal” as she calls them) where the imagination is allowed to dominate consciousness before the mind is caught, and frozen, in a pragmatic net of language and concepts that are required if we are going to successfully negotiate and survive in the world.

The experiences she recounts include the writing of her first poem (in, of all places, geometry class), and the opening lines of her first novel in the austere silence of the Swedish stacks of a university library; her experiences over several years in her twenties of living in the jungles of Central America where she found a place in the physical world that embodied the imaginative exaltations of her fevers; the long creative drought when she was turning herself into a professional scholar and university teacher; her creative breakthrough later on during a period of deep misery; and her exploration of ways to contact the most powerful emotional sources of her creativity that escaped the self-destructive strategies of many poets and artists of the past.

There is a poetry of exaltation and a poetry of serenity – in the past often called “romantic” and “classic”; in the modern world, “modernist/postmodernist” and “conservative,” “authentic” and

“bourgeois.” Mackey, for good reasons, wanted the exaltation of the romantic without paying a price for it in derangement and self-destruction. And her book ends by describing the success with which she found her way to the Holy Grail of poetry: a means of contacting the demons and gods of poetic creation without letting them tear her to pieces. And the result has been the discoveries she has made in the secret places of her mind and graced her readers with over the years.

And yet the final secret remains. We all have dreams, and yet not all our dreams are beautiful, meaningful, or powerful. Indeed most of them are rather banal reconnoiters of the less-interesting corners of our everyday minds. Whereas Mackey’s explorations have yielded, through a combination of courage, determination, relentless work, searching intelligence, and demanding and shaping taste, along with her deep dives into the wordless, conceptless, formless seas of her subconscious – the ocean of childhood from which we all emerged – poetry of a dazzling beauty and rare profundity. And for this we must always be grateful, though still mystified.

Este è um poema criando-se

this is a poem creating itself em um idioma

in a language you don’t understand

think of it as a dancer

whose face is hidden behind a beaded veil

uma bebida prieta a black drink that

lets you hear jaguars speak

a city seen from 20,000 feet

um barhulo/ a noise that wakes you à meia-noite

tropeçando tropeçando stumbling through the

darkness knocking at your door

— “This Is a Poem Creating Itself,” from Sugar Zone

Mary Mackey’s Creativity: Where Poems Begin can be ordered here or from your local bookstore.

_____

Christopher Bernard is a novelist, poet and essayist as well as critic. His books include the novels A Spy in the Ruins, Voyage to a Phantom City, and Meditations on Love and Catastrophe at The Liars’ Café, and the poetry collections Chien Lunatique, The Rose Shipwreck, and the award-winning The Socialist’s Garden of Verses, as well as collections of short fiction In the American Night and Dangerous Stories for Boys. He is also a co-editor and founder of the semiannual webzine Caveat Lector. His children’s stories If You Ride a Crooked Trolley . . . and The Judgment of Biestia, the opening stories of the Otherwise series, will be published in the fall of 2023.

Christopher Bernard reviews Cal Performances’ production of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower in Zellerbach Hall

A Seed on Rich Soil

Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower

Cal Performances

Berkeley

Exactly thirty years ago, a novel appeared, with little fanfare or publicity, that would have disappeared under the ocean of similar books that die on the day they are born if it hadn’t been for the kind of chance that has saved more than one book from oblivion.

It found a handful of readers – just the right, lucky handful – who passed the word along to other readers, who did the same for others, until it created a union of enthusiasts who found its disturbing vision compelling and entirely too plausible, yet strangely beautiful. The author continued to work in obscurity for many years, and was just attaining recognition as a significant voice in American literature when she died, at 59, in 2006.

The book in question is Parable of the Sower, the author Octavia E. Butler. And the vision that commands it, and its sequel Parable of the Talents, is the basis of the gospel plus rockabilly opera written and composed by Toshi Reagon and Bernice Johnson Reagon and performed at UC Berkeley’s Zellerbach Hall that I saw on this year’s Cinco de Mayo.

The 1993 novel is set in Los Angeles in 2024, its sequel a few years later. And its vision, at the time it quietly entered the world, must have seemed at the margins of plausibility, a Mad Max version of California fed with cocaine, speedballs, and the rest of the paranoid arcana of the drug culture. Seeing the story play out in 2023 – after the bedlam of covid, the compulsive self-harming of San Francisco, capital of the worldwide technological empire that is shredding society while spewing billionaires like an army of combines across a field of ripe wheat, the descent of America into a cold civil war between the impossibly wealthy and the politically disenfranchised, culturally despised, and economically impoverished – makes one believe the notion of the oracular power of art may not be entirely a professor’s dream and a teenager’s nightmare, but mere palpable reality.

The opera the story has spawned, through the brilliant talents of the Reagons (a mother-and-daughter team of writers and composers – excuse me, but isn’t that the most inspiring and heart-warming thing ever?) and a much-talented ensemble of instrumentalists, singers and dancers (the two last often the same), created a thoroughly inspiring evening for a packed and extremely diverse audience in the heart of the UC Berkeley campus.

The opera plays without intermission for a little over two hours; a probably wise decision, since a lengthy break between the two parts may well have weakened the tension built up so skillfully in the first hour. Though the performance is called an “opera,” it feels more like an oratorio, since there is less emphasis on an involved plot and dramatized action than on a series of musical and dance numbers presenting states of mind, moments of crisis, experiences of trauma and loss, and brave attempts to make sense of them and take away, in the teeth of destruction and chaos, some shred of moral and spiritual guidance, some basis for faith and hope.

The plot insofar as there is one revolves around a young woman of color, named Lauren Oya Olamina (a luminous Marie Tatti Aqeel), who lives with her family in a poor community walled away from a collapsing outside world and trying to find meaning in an old-time religion under the leadership of the girl’s reverend father. Between musical numbers that fluctuate between the young girl’s fears and longings and the anguish (alleviated by a strenuous but sometimes forced optimism) of her community, she retreats to a notebook where she gathers her thoughts in search of a meaning her father’s faith has failed to give her.

The tensions within the community, exacerbated by having no escape to the outside world, explode at last, destroying the wall that has been both protection and prison, and scattering a group of destitute survivors, among them Lauren, wandering across a landscape devastated by the forces of the postmodern world, toward a nameless destination “to the north.”

When the wall falls, Lauren loses her family and, joining in destitution and poverty in her march across a California wilderness while hiding her vulnerable youthfulness and femininity behind a masculine cloak, she leads her group – a “chosen family” of the homeless, despairing and forlorn – with a new faith, a new religion that she calls “Earthseed,” with a text written by herself: “The Books of the Living,” and a central doctrine exalting “change” as the essence of the divine.

But there is desperation in her new faith. Indeed, it is a tragic doctrine, one that Lauren herself does not seem willing to face. Because to worship change for its own sake is to worship death. Those who exalt “change” seem to think that “all things change (but I’ll still be here).” But that is not so: if all things change, it is precisely you who will not be here.

The resemblances between the 2020s imagined in the mid-90s and their actualities today are often uncanny. And Butler’s vision, conveyed with both passion and enchantment by the Reagons and their ensemble, gripped this viewer with a persuasiveness, long after the last chord, that is rarely sustained for so long. Here indeed (to use Keats’s famously controversial phrase) beauty was truth, truth beauty.

The performance, despite the grimness of the story, ended on a note of hope that avoided both bromides and fraudulent optimism (a curse of much serious art with popular pretensions). It concluded with a rousing musical version of the biblical parable that gives the work its title. For those who don’t recall it, it amounts to the basic truth that, though many seeds of the sower fall on barren ground, on rocks and among thorns, some few fall on rich soil and fertile land, and these take root and thrive and grow to flower and fruit “a hundredfold.”

Toshi Reagon served as both introducer and guide into Butler’s world; she was also lead guitar and commenting “folk singer” bringing Butler’s vision up to date in a way the author would no doubt have enthusiastically approved. Toshi was aided by a strong singing duo, Abby Dobson and Shelley Nicole, and a backup band that sounded far larger than its five members.

After the show, there was a wide-ranging discussion with five of the performers. Toshi left us with much wisdom to savor, not the least of which was this: “There are those who believe what they know, and those who deny what they know. Whatever you do, believe what you know.”

Amen to that.

_____

Christopher Bernard is a co-editor and founder of Caveat Lector. He is also a novelist, poet and critic as well as essayist. His books include the novels A Spy in the Ruins, Voyage to a Phantom City, and Meditations on Love and Catastrophe at The Liars’ Café, and the poetry collections Chien Lunatique, The Rose Shipwreck, and the award-winning The Socialist’s Garden of Verses, as well as collections of short fiction In the American Night and Dangerous Stories for Boys. His children’s stories If You Ride a Crooked Trolley . . . and The Judgment of Biestia, the opening stories of the Otherwise series, will be published later in 2023.

Christopher Bernard reviews Cal Performances’ Blank Out, an opera by Michel van der Aa

The Trauma of Memory

Blank Out

Cal Performances

Berkeley

How many of us have ever been caught in a lie? Or caught others in a lie? Or caught ourselves in a lie – to ourselves?

It’s likely few can say, to any of these questions, “Not me. No. Not ever.”

Though when it comes to a trauma – an accident, a crime, a moment of misjudgment with catastrophic consequences – there may be many who adamantly assert, “No! Not me! Not ever!”

Blank Out, a compelling chamber opera by the Dutch composer Michel van der Aa, who conceived, directed and developed its libretto, probed these and related matters in a violently imaginative way – enigmatic at first, sometimes mystifying, but in the end deeply moving – at a performance I saw at UC Berkeley’s Zellerbach Hall on a recent April evening.

A work that addresses the psyche’s dialectics of reality and denial in the aftermath of loss, it bracingly incorporates film, music and live action to examine the darker corners of authenticity. In the opening act of what amounts to a three-act drama played without pause, a beautiful young woman (played by Sweden’s celebrated Mozart soprano Miah Persson) takes the stage to sing, in fragments of sometimes surreal verse, of an event long ago at her seaside home – an event she must relive over and again, without end or resolution, in which her young son disobeyed her orders not to go out further in the water than “up to his belly button,” and drowned.

A screen projects at first one, then two images of her as she sings in duet, then in trio with herself. She unwinds a bit of narrow cloth from a spool. She walks to a table at the edge of the stage and manipulates a dollhouse-sized cottage and a fragment of its neighborhood in front of a camera. The image abruptly appears onscreen and she walks and sings before it, creating a curiously uncanny sensation, seeing her blur and blend in with the toy home; memory, fantasy, childhood dream and present-day illusion, enwrapped in a single embodiment.

But there is something off; this is not just an elegy for a lost child, though at one point the woman stops singing and speaks directly to the audience. The lovingly infatuated young mother describes the special joys and oddities of her boy – his games, his little dramas and comedies, his pretending his beach blanket was a flying carpet held to earth by little piles of stones at its corners – with a transparent pleasure that seems to preclude mourning or lament. The lack of tears is both moving and strange. She describes their last evening together, when the television set caught fire and while it was being repaired, they drove in their VW beetle to a nearby eatery for a pizza (his very first).

The screen begins fluctuating between images of the dollhouse cottage and of the real home it is based on, isolated at the far edge of a field and toward which the camera moves as on an angel’s-eye drone. The woman becomes increasingly abstract as images of the boy are seen distantly, just visible turning a corner of the house, when the camera cuts to a close up and the “boy” suddenly dominates the screen – no boy now but a middle-aged man.

The screen projection changes with equal drama: the 3D goggles I was given in the lobby now prove their worth as the film goes three-dimensional, and a dialectical drama between stage and screen – the screen seeming to become an extension of the stage, the stage an extension of the screen – incorporates the drama we are seeing: two fantasies become two realities, two realities two wishful dreams.

The boy’s dream is of what might have been against the overwhelming guilt of reality on that day decades ago: it was not the boy who drowned, but his mother who drowned saving him.

The second act is commanded by the exceptional singing of Roderick Williams as he enacts a dream of loss and remembrance while his young mother fades in and out, sometimes one, sometimes multiple, always alone, on the stage infinitely far away from him: the screen is a wall between them, built of reality and fantasy, of light and stones. He becomes the young boy, playing his carefree games, teasing his mother, tossing melodies back and forth with her, then in anguish remembering his one misstep that led to a loss that cannot be repealed.

The third act is a transcendent blending of the 3D film, the stage, the dollhouse cottage, the actual home and its memories, the music (now combining a chorus with the continuing sampler and electronic accompaniments to the singing), and even the VW beetle, symbol, or perhaps a better word is incarnation of the insouciant joys and silliness of childhood, the happy discovery of pizza, the nightly child’s baths, the boy’s favorite game of jumping from chair to chair in the living room (because touching the “lava-covered” floor would mean instant death), the funny episode with the hot pebbles he once swallowed because he wanted to “taste their heat,” the endless non-tragedies, the exuberant follies, and the one endless tragedy that ended childhood in a rage of flying stones and wrecked car and a storm of autumn leaves and blinding light beneath the silence of the sea.

The choral additions were sung by the Nederlands Kamerkoor. The libretto includes fragments from the writings of the South African poet Ingrid Jonker, who died young of suicide.

_____

Christopher Bernard is a co-editor and founder of Caveat Lector. He is also a novelist, poet and critic as well as essayist. His books include the novels A Spy in the Ruins, Voyage to a Phantom City, and Meditations on Love and Catastrophe at The Liars’ Café, and the poetry collections Chien Lunatique, The Rose Shipwreck, and the award-winning The Socialist’s Garden of Verses, as well as collections of short fiction In the American Night and Dangerous Stories for Boys. His children’s stories If You Ride a Crooked Trolley . . . and The Judgment of Biestia, the opening stories of the Otherwise series, will be published later in 2023.

Christopher Bernard reviews the Kronos Quartet at Zellerbach Hall

The Ghosts of Space and Time

Kronos Quartet and Wu Man (pipa)

Zellerbach Hall

Berkeley

After a winter of bomb cyclones and atmospheric rivers, the Kronos Quartet – the legendary San Francisco ensemble that reinvented the string quartet for our time – gave one of its most satisfying concerts in memory on a blissfully rainless first of April at Zellerbach Hall in Berkeley as part of Cal Performances. April Fool’s Day and the feast of Hilaria were soon forgotten in a concert that sent at least one person in the audience home wrapped in the mystery of other times and places.

It’s only fair to say that not all of the quartet’s many and various experiments in making the string quartet “relevant” come off. And sometimes my faith in new music has been tested. But tonight there were fewer distractions than revelations, all of the latter involving, and often led by, the quartet’s collaborator, Wu Man, a winsome, deeply gifted musician who makes difficulty seem as easy as dreaming.

Wu Man, it’s fair, if paradoxical, to say, is the world’s most renowned performer on an instrument almost nobody knows – the pipa. This lute-like instrument from China, with a long, thick neck and a pear-shaped belly, has a history going back two millennia. Both strummed and plucked, it added delicious bite and spice to the woody rosin and catgut of the western strings. Two of the concert’s revelations were composed Wu Man, working with American composer Danny Clay to transpose her musical inspirations into legible scores.

Glimpses of Muquam Chebiyat is adapted from the traditional Uyghur Muqam Chebiyat, which Wu Man discovered through the musicians Sanubar Tursun and Abdullah Majnun, members of this persecuted minority in China.

Awareness of the oppression of the Uyghur population makes the music even more poignant, but the political dimension is by no means needed to focus one’s attention. A soft and intensely lyrical melody, played with profound sensitivity by the quartet’s remarkable violist Hank Dutt, sets the tone for the first half of the piece and is passed and varied delicately between the five instruments. The second half is a dance, curiously in the classic western three-quarter’s meter, charged with the sharp plucking of the gleeful pipa.

Wu Man’s second piece was titled Two Chinese Paintings. The first short movement, called “Ancient Echo,” is graced with delicate arpeggios based on a pipa scale from ninth century China. The second is a variation of “Joy Song” (Huanlege) from a classic collection called “Silk and Bamboo” – a clattering, happy piece that, making few concessions to western scales and harmonies, drew out the most compelling, and totally unpredictable, joys.

The concert’s greatest revelation was saved for the second half, though perhaps I shouldn’t call it a revelation for myself, because I first heard it, with the same instrumentalists, many years ago in San Francisco, in a concert about which I now can say definitively that I will never forget it. And yet, seeing and hearing it again was, if anything, a new revelation – of the ghosts of time and space, which seemed almost to vanish as I felt as though I were reliving the remarkable experience I had then.

The piece was one of the earliest works presented to American audiences by a composer who has become, if not a household name, at least a name to conjure with in contemporary music: Tan Dun, winner of too many awards to mention, and a leading conductor as well as composer. For me, Ghost Opera is one of the unquestionable masterpieces of contemporary music – a work of profoundly satisfying audacity.

The work is fully, yet economically, produced, on a stage that is almost completely dark, for string quartet, pipa, water, stones, paper (including a long swooping drape-like scroll, brightly lit, like the broken piece of a Chinese ideogram), metallic instruments including Chinese cymbals, watergongs, and a large pendent gong, and Chinse vocalizations from the instrumentalists, like wailing cries of the dead, the living, and the unborn.

There is no story as such, except for a set of variations, begun on David Harrington’s haunting violin, of a melody from Bach that is rendered both malleable and ghostlike as it winds through a gamut of transformations based on both western and Chinese scales, harmonies, and rhythms as it passes from player to player.

The stage is, as mentioned, almost entirely dark throughout, with pools of light above large glass bowls of water, where the water is performed in rituals of the cleansing of hands, and elsewhere lighting individual players, later in groups, then returning to individuals as they disperse and disband back into darkness and silence, “under the rule of Heaven.”

A tall narrow, translucent scrim stands in front of a riser, where, first, the cellist (a fine Paul Wiancko) is shown in dramatic shadow cast by a brilliant light at the back of the stage, and, later, where Wu Man stands, like a ghost just visible as she performs, sometimes responding to, sometimes leading, the more-earthbound quartet.

There is much imaginative use of space both onstage and off – for instance, in the first of the five seamless movements, the violist performs in the audience in response to solo violinist and pipa player at different corners of the stage like distant stars in a moonless night.

Tan Dun has stated that his inspiration for the piece was the “ghost operas” of China, a 4,000-year-old tradition in which the living, the dead and the unborn speak to each other across the boundaries of time and space.

The result was, again, an experience, both dramatic and musical, of unique intensity and beauty and of a profundity that lies at the far end of words – though Tan Dun uses, along with Bach’s music, the words of Shakespeare (famous lines from The Tempest: “We are such stuff / As dreams are made on. . . .”) – words that seemed almost unnecessarily specific, as the work as a whole both expresses them and contests them: if those works speak true, not even a ghost will survive – and yet we have just seen their power.

The concert began with a rousing work by the inventor of minimalism in music, Terry Riley: the first movement of The Cusp of Magic, where David Harrington plays a peyote rattle and second violinist John Sherpa plays pedal bass drum while grinding grandly away at his fiddle, and Wu Man keeps everyone sharp with her pipa. The piece was performed against a background of electronic music and sound sampling compiled by David Dvorin.

The first half of the program ended with the one piece in which Wu Man did not perform: Steve Reich’s Different Trains, a piece I felt overstayed its welcome and has not aged well, though the original concept was of interest.

The enthusiastic audience was provided a delightful encore after Tan Dun’s transcendent achievement: an arrangement for the evening’s ad-hoc quintet of Rahul Dev Burman’s Mehbooba Mehbooba (Beloved, O Beloved).

The audience left for home with the strange but striking sense of being deeply moved – and yet feeling very merry indeed.

_____

Christopher Bernard is a co-editor and founder of Caveat Lector. He is also a novelist, poet and critic as well as essayist. His books include the novels A Spy in the Ruins, Voyage to a Phantom City, and Meditations on Love and Catastrophe at The Liars’ Café, and the poetry collections Chien Lunatique, The Rose Shipwreck, and the award-winning The Socialist’s Garden of Verses, as well as collections of short fiction In the American Night and Dangerous Stories for Boys.

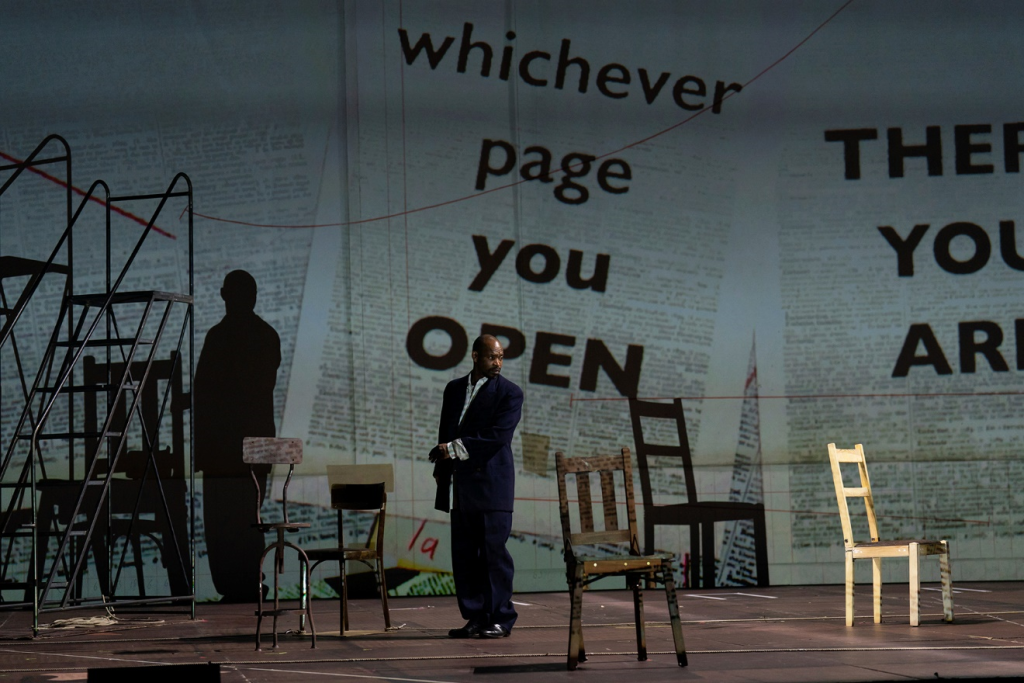

Christopher Bernard reviews William Kentridge’s Sibyl at Zellerbach Hall (Berkeley, CA)

The Mouth Is Dreaming

SIBYL

William Kentridge and collaborators

Zellerbach Hall

Berkeley

A review by Christopher Bernard

The climactic event of an academic-year-long residency at UC Berkeley by the celebrated South African artist William Kentridge, was the United States premiere at Cal Performances of SIBYL, the latest example of his deeply witty, darkly lyrical, postmodernly brilliant, if intermittently satisfying (though the two last qualifiers are perhaps redundant), but exhilarating suspensions in organized theatrical chaos.

Beginning as a reluctant draftsman, and having gone through a succession of dead-end careers in his youth (as the artist has described in interviews), Kentridge finally embraced the fact that his deepest gift lay in drawing; in particular, his capacity to turn charcoal and paper into an infinite succession of worlds through the dance of mark, smear, and erasure, similar to those of a master central to him, Picasso. Through drawing, he was able to extend his explorations into other fields of interest, including sculpture, film, and theater, above all opera and musical theater, attested to by his celebrated productions of operas by Berg, Shostakovich, and Mozart.

The artist also realized that it was precisely this capacity for creation itself – though perhaps a better term for it might be perpetual transformation – that stood at the heart of what we must now call his peculiar, and peculiarly fertile, genius (a term I do not use lightly – Mr. Kentridge is one of the few contemporary artists whom I believe fully deserves the word).

The latest hybrid work combining his gifts is a theatrical kluge of disparate elements that meld into a uniquely gripping whole, though there are gaps in the meld I will come to later.

The central idea is the Cumaean Sibyl, best known from Virgil’s Aeneid and paintings by Raphael, Andrea del Castagno, and Michelangelo. A priestess of a shrine to Apollo near Naples, she wrote prophecies for petitioners of the god on oak leaves sacred to Zeus, which she then arranged inside the entrance of the cave where she lived. But if the wind blew and scattered the leaves, she would not be able to reassemble them into the original prophecy, and often her petitioners would receive a prophecy or the answer to a petition not meant for them, or too fragmentary to be understood.

The performance opens with a film with live musical accompaniment, called The Moment Is Gone. It spins a dark tale of aesthetics and wreckage involving the artist in witty scenes with himself as he designs and critiques his own creations (a key link in his own transformations), and, in two parallel stories, Soho Eckstein (an avatar of the artist’s darker side who frequently appears in his work), a museum modeled on the Johannesburg Art Gallery, and the Sisyphean labors of zama zama miners – Black workers of decommissioned diamond mines in South Africa; work that is as dangerous and exhausting, and often futile, as it is illegal. Leaves from a torn book blow through the film bearing Sybilline texts: “Heaven is talking in a foreign tongue,” “I no longer believe what I once believed,” “There will be no epiphany,” and long random lists of things to “AVOID,” to “RESIST,” to “FORGET.” The museum is undermined and eventually caves in at the film’s climax, leaving behind a desolate landscape surrounding an empty grave.

The film is silent, though its exfoliating imagery almost provides its own music, an incessant rustling of forest leaves like those of the original Sibyl’s cave. The live music is composed by Kyle Shepherd (at the piano) and, by Nhlanhla Mahlangu, choral music sung by a quartet of South African singers, including Mr. Mahlangu. The choral music is based on the hauntingly quiet isicathamiya style of all-male singing developed among South African Blacks in eerie parallel to the spirituals of American Black culture, and for similar reasons: to try to console them for a seemingly inescapable suffering caused by white masters in a brutally racist society.

The second half is called Waiting for the Sibyl, in six short scenes separated by five brief films. The live portion presents half a dozen or more singers and dancers in scenes from the life of the Sibyl acting out her half-human, half-divine mission. Several of the scenes also incorporate film projections of drawings in charcoal and pen and pencil, black-ink splashes dissolving into mysterious exhortations (some of the visuals are powerfully reminiscent of Franz Kline’s black paintings on newspaper and phone directory pages from the 1950s), and Calder-like mobiles and stabiles, the most powerful of which spins slowly for several minutes, turning from an ornate display of stunningly dark abstractions into a climactic epiphany of resplendent order: the divine oakleaves of the Sibyl upon which we can read our destiny if we are lucky enough to find the one meant for us. The claim “There will be no epiphany” is here startlingly, and definitively, denied.

A line of bright lights along the front edge of the stage projects the shadows of performers and props against back screens and walls to effects that are both compelling to watch and symbolic of the dark side of every illumination. In several of the scenes, Teresa Phuti Mojela, playing the Sibyl herself, dances in magnificent passion as her shadow is projected grandly on the screen behind her to the right of which a flashing darkness of charcoal and ink from the artist’s hand dances beside her.

In other scenes, the treachery of the material order is allegorized in a dance of chairs moving apparently by themselves across the stage and collapsing just when a poor human being needs to rest on one from the unbending demands of the material order of living.

In another scene, a megaphone takes over the stage and barks orders across the audience, many of them transcriptions of the oracular pronouncements on the Sibylline leaves: “The machine says heaven is talking in a foreign tongue.” “The machine says you will be dreamt by a jackal.” “The machine will remember.” Though then the megaphone – stand-in for the machine – seems to turn against itself: “Starve the algorithm!” it demands, shouting over and over, to several unequivocal responses (“Yes!” “You said it!”) from the audience I was in.

One of the most dazzling of the short films is an immense one-line drawing that begins as a dense chaos of swirling squiggles in one corner that eventually builds into an elaborate, precise, wondrous, surreal but perfectly legible drawing of a typewriter. But the draftsman does not stop there, he continues drawing wildly, apparently uncontrollably until the screen is a thick liana, a fabric of chaotic twine, the typewriter slowly sinking beneath the chaos of a creation that cannot stop. This is a nearly perfect example of the perpetual transformation – one might say, of existence itself – that is one of Kentridge’s central themes.

SIBYL is filled with such brilliant and, for me, unforgettable moments, as I have learned to expect from this artist after he first invaded my mind in a retrospective I saw in 2010, and in the following years in such masterful creations as “The Refusal of Time.” But the piece is not without weaknesses. The artist admits, in interviews, that he does not know how to tell a story. And that is clearly true – and in most of his work, it doesn’t matter. But for a live performance, something like a narrative arc is required for a piece to cohere and satisfy at least this spectator. The arc can be as abstract as you please (such as in a Balanchine ballet), but it needs to be there. And it is not present in the second part of SIBYL (where it needs to be) nor, a fortiori, in the work as a whole. The production provides a fascinating evening, loaded with ore; my only complaint is that it could have been even better than it is. For example, I was expecting a fully climactic conclusion. There is none; it just stops. The ending is merely flat. Postmodernly unsatisfying.

Among the things that stay stubbornly in memory are the vatic sayings of the Sibyl herself, strewn across screen and stage as at the mouth of the priestess’s cave: “Let them think I am a tree or the shadow of a tree.” “It reminds me of something I can’t remember.” “We wait for Better Gods.” “The mouth is dreaming.” “Whichever page you open” “There you are.”

_____

Christopher Bernard’s third collection of poetry, The Socialist’s Garden of Verses, won a PEN Oakland Josephine Miles Award and was named one of the “Top 100 Indie Books of 2021” by Kirkus Reviews. He is a founder and co-editor of the webzine Caveat Lector.