The Search for the Source

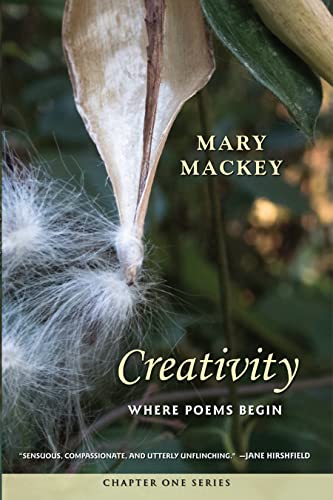

Creativity:

Where Poems Begin

By Mary Mackey

Marsh Hawk Press

The greatly talented Mary Mackey’s slim but profound and beautifully written book has a slightly disingenuous title. If you are expecting a scholarly exploration of the creative mind such as you will find in Arthur Koestler’s classic work The Act of Creation or Silvano Arieti’s Creativity: The Magic Synthesis, you may be disappointed. Or if you expect something like those works but focused on literary creativity, you may also be.

But what you will get is just as worthwhile. I can see why Mackey did not call her book “My Creativity: Where My Poems Begin,” because, though no sufferer from imposter syndrome, she is too courteous toward her reader to thrust her ego unapologetically into the foreground. Even the most brilliant writer realizes that the world does not revolve entirely around her. But the revised title is an exact description of what we find in these pages.

That Mary Mackey is not better known is a bit of a scandal, because we are in need of her eloquence and originality. But I have long given up on the taste of the public and many of its would-be literary critics – eloquence and originality have been replaced by vulgarity and imitativeness (and aesthetics has long been replaced by politics) as the keys to success in contemporary America, may the gods and the Muses forgive all of us.

Unhappily, even posterity cannot be entirely depended on to have taste, intelligence or judgment. If Darwin rules, we can hardly expect natural selection to be wiser or kinder than we have been. And contemporary culture is beginning to look more and more Darwinian with each passing season. In the meantime, a few lucky readers will benefit from her books. And this is one of the gems among them, and is likely to ignite interest in her other books.

What, after all, is this nebulous thing we call “creativity”? Every time we speak we are engaging in a creative act, as the linguist Noam Chomsky regularly points out. We invent an original response to every event that happens to us – every moment is fresh, novel, unrepeatable, however boringly familiar it might seem to our half-asleep minds and benumbed senses. Every night, every dreamer creates a new universe.

But there is a hierarchy in creativity: though there is clearly a relationship between them, there is also a qualitative difference between this kind of creativity, shared by all sentient beings, and the creative leaps that result in the discovery of relativity, the painting of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, writing Ulysses, or composing Bob Dylan’s anthems from the ‘60s.

Or writing a book like Mary Mackey’s prize-winning poetry collection The Jaguars That Prowl Our Dreams or her other collections (which include Skin Deep, Sugar Zone, and Travelers With No Ticket Home) and her densely poetic novels such as Immersion, A Grand Passion, and The Valley of Bones.

There is another difference: most successful artists, grateful for their creativity, or merely taking it for granted (and perhaps afraid to look too searchingly into a gift horse’s mouth for fear the horse will bolt at reason’s first cool poke), they revel in its fruits but don’t make a quest to discover its sources. Mackey is not satisfied merely to enjoy her gift; she has decided to try to find out where it comes from, what causes it, how she has become to be so graced.

And the result is this memoir of her creativity.

It has often been said that the most valuable gifts often come in small packages, and many a short book holds more substance than a far weightier tome. The saying surely applies here.

To say that Mackey has found the ultimate source of her phenomenal gift – the source of the Nile, the Higgs boson that transforms chaos into resplendent form – might be going too far, but to say she has come as close as it might be possible to go is, I think, not claiming too much.

Her book is divided into thirteen short chapters, most of them concentrating on moments in her life when she became most aware of the assertively creative currents within her as they broke into consciousness. These include experiences of intoxicating fantasy during the extreme fevers Mackey has had since she was an infant; experiences that drove her mind into visions and ecstasies that became key to how she engages layers of the mind (“preverbal” as she calls them) where the imagination is allowed to dominate consciousness before the mind is caught, and frozen, in a pragmatic net of language and concepts that are required if we are going to successfully negotiate and survive in the world.

The experiences she recounts include the writing of her first poem (in, of all places, geometry class), and the opening lines of her first novel in the austere silence of the Swedish stacks of a university library; her experiences over several years in her twenties of living in the jungles of Central America where she found a place in the physical world that embodied the imaginative exaltations of her fevers; the long creative drought when she was turning herself into a professional scholar and university teacher; her creative breakthrough later on during a period of deep misery; and her exploration of ways to contact the most powerful emotional sources of her creativity that escaped the self-destructive strategies of many poets and artists of the past.

There is a poetry of exaltation and a poetry of serenity – in the past often called “romantic” and “classic”; in the modern world, “modernist/postmodernist” and “conservative,” “authentic” and

“bourgeois.” Mackey, for good reasons, wanted the exaltation of the romantic without paying a price for it in derangement and self-destruction. And her book ends by describing the success with which she found her way to the Holy Grail of poetry: a means of contacting the demons and gods of poetic creation without letting them tear her to pieces. And the result has been the discoveries she has made in the secret places of her mind and graced her readers with over the years.

And yet the final secret remains. We all have dreams, and yet not all our dreams are beautiful, meaningful, or powerful. Indeed most of them are rather banal reconnoiters of the less-interesting corners of our everyday minds. Whereas Mackey’s explorations have yielded, through a combination of courage, determination, relentless work, searching intelligence, and demanding and shaping taste, along with her deep dives into the wordless, conceptless, formless seas of her subconscious – the ocean of childhood from which we all emerged – poetry of a dazzling beauty and rare profundity. And for this we must always be grateful, though still mystified.

Este è um poema criando-se

this is a poem creating itself em um idioma

in a language you don’t understand

think of it as a dancer

whose face is hidden behind a beaded veil

uma bebida prieta a black drink that

lets you hear jaguars speak

a city seen from 20,000 feet

um barhulo/ a noise that wakes you à meia-noite

tropeçando tropeçando stumbling through the

darkness knocking at your door

— “This Is a Poem Creating Itself,” from Sugar Zone

Mary Mackey’s Creativity: Where Poems Begin can be ordered here or from your local bookstore.

_____

Christopher Bernard is a novelist, poet and essayist as well as critic. His books include the novels A Spy in the Ruins, Voyage to a Phantom City, and Meditations on Love and Catastrophe at The Liars’ Café, and the poetry collections Chien Lunatique, The Rose Shipwreck, and the award-winning The Socialist’s Garden of Verses, as well as collections of short fiction In the American Night and Dangerous Stories for Boys. He is also a co-editor and founder of the semiannual webzine Caveat Lector. His children’s stories If You Ride a Crooked Trolley . . . and The Judgment of Biestia, the opening stories of the Otherwise series, will be published in the fall of 2023.