TRUJILLO You are a town spun in history, from Cristóbal Colón’s last voyage to a port protected from pirates by the Spanish Fortaleza Santa Bárbara, from the first capital of this nascent country to the execution of filibuster William Walker. Many had their embassies here: France, Spain, England, the US. And both United Fruit and Standard Fruit left their cobwebs, too. ~ ~ ~ I wander through the odd clutter of Señor Galván’s museum. A band’s musical instruments, collections of coins and bills. Ship anchors and moorings. Old wine and patent medicine bottles. Treadle sewing machines, branding irons, the chair and bed of a man who lived to be 106. Mayan artefacts from the sierra. Assorted alligator and shark skulls. Caged monkeys reaching for a human hand. And from the Companies themselves. A Standard Fruit lamp and sugar cane press. A United Fruit telephone and fan, railroad jacks, a brakeman’s lantern. And a 1940s brick of the Yunay Fruit Co. Mamita Yunai … United Fruit Out front corrodes the wreckage of a C130 that crashed near Puerto Castilla. All 21 crewmembers were killed from Howard AFB in Panama. It was never explained to us what this plane was doing here that 22 January ’85 … in Contra territory. ~ ~ ~ I am spellbound by the tangled web. I pass days talking with Mr Galván and in the public library unraveling history. For only a short two years did Vaccaro Brothers and Co (later Standard Fruit) spin its domain eastward to here. Those siblings had their fincas of sugar cane and syphilis-curing sarsaparilla. They timbered the precious hardwoods of these surrounding jungle hills. Afterwards United Fruit came (in 1904, Señor Galván says) and later hid under the guise of the Trujillo Rail Road Co. For lands in this area, it promised to build the railroad to Jutigalpa and beyond to Tegucigalpa. It laid the line from port to plantations: Puerto Castilla and Trujillo to Olanchito, Tocoa, Savá and no further. Amid excuses of land blackened by sigatoka, United left in 1940, before the Honduran government could confiscate the fincas and rails for not fulfilling its contract. When the Boston Octopus pulled out, families sold their furnished homes for a mere 400 Lempiras. Still, to this day, some rich people have a hundred houses or more. And so this town fell into a quiet backwater. Black Caribe and whiter ladino intermarried. Over the years, the memories faded. Only Mr Galván remembered why the Fruit Company submerged a train east of the pier: To protect the beachhead from erosion. The plantations way out yonder changed once more to Standard Fruit. In the 1980s, the US-Contras arrived with training camps and cocaine-for-arms trade routes. Within these jungle swamps, the US military had clandestine bases (or so say its veterans, in fear-hushed voices). And little by little, the foreign travelers came, seeking the tranquil sea, the safe beaches, a town free from crime. A new posh resort is built, The Christopher Columbus. Ninety-two full-time staff but few guests. The locals say it’s a CIA den owned by Ollie North, Secord and former-Contra friends. And after almost 90 years, Standard Fruit makes its return. A high concrete wall with barbed wire surrounds the eight or so unseen houses within. Strong floodlights safeguard the grounds. These are the homes of the CEOs who work at Puerto Castilla. ~ ~ ~ One evening in a pleasant hide-away café – with rattan chairs, glass-topped tables, plants, English newspapers – an ex-pat United Statien tells the owner and me her family wants to move from Tela. The scene is getting too heavy there – the crime, the cocaine. They have found a house near the Company’s complex. But it has no electricity. They must ask Standard Fruit for permission to put it in. Its security comes first. When I first came to Trujillo during Christmas holidays in ’93, I could stroll alone several kilometers along the beach. I’d leave my belongings on the powdery sand and swim in that crystal-blue Caribbean. But two years later, with clenched fists and teeth, trujillanos tell me, It isn’t safe any longer to walk those isolated stretches. Inlander ladinos are migrating in search of the work the tourism surely brings. But there are no jobs … One night from Olanchito they came to the Garífuna bars in Cocopando. A white woman danced with a black man. Six redneck ladinos shot up the place. Two more years or so pass. One evening, walking through town, seven foreigners are robbed and stabbed. One dies. And that cocaine now floats like a blizzard along these ex-Contra coastal routes.

Category Archives: CAPUTO

Short essay from Lorraine Caputo

QUIRIGUÁ

A rocky road studded with jade and copper-blue rocks cuts for several miles through banana plantation, heading for the heart of the Maya past. This land formerly of Cuauc Sky, Jade Sky … formerly of the United Fruit Company, now (in this late-December of 1993) of DelMonte.

A hedge of clavel separates road from field. Their bright red flowers cascade towards the dustraised by passing trucks and tourist buses. Three men ride up on bicycles, a small bunch of bananas slung from the handlebars. They pass a sign. PROHIBITED TO CUT RACIMO DE BANANO.

The finca stretches to either side, laced with irrigation ditches and overhead cable lines. Broken sunlight shifts on the ground with each sway of the broad green leaves splitting into thick frays. Large purple and red teardrop flowers bow. As each aged petal curls away, the delicate fingers of a new bunch of bananas is revealed. The growing racimo is protected from sun, dirt, rain by blue perforated bags. Trees are tied to one another with a thin white cord to keep them erect beneath the weight of heavying fruit.

Four workers emerge from a field. One has a small bundle of bananas in hand. Their loose rubber boots slap against calves. The lunchtime silence interrupted by birdsongs and the sound of water erupting from upright black pipes. A circulating sprayer pounds it down upon the leaves like a torrential rainstorm. The road wettens, muddies. It continues through a guarded gate. HALT PRIVATE PROPERTY BANDEGUA.

An old rail line passes through its own yellow and black barrier. Across the road and rusty tracks lie the ruins of Quiriguá.~

~ Upon entering the site the banana forest gives way to palms and amates, ceibas and almond trees. Elaborately carved stelae rise seven, eight, nine meters towards a rain-threatening sky.

This Quiriguá once was a colony of Copán only 50 kilometers away as the cuervo flies.But Cuauc Sky chose independence. He captured 18 Rabbit and beheaded that Copán rival. These stones record the history. This Maya kingdom, tough, faded with the rule of Jade Sky. The spirit houses and monuments sank into the returning jungle.

Many centuries later arrived a new conqueror: United Fruit. It stretched its fincas to the hills that roll down to the Río Motagua that once divided those great Maya kingdoms, that divided the great rival fruit companies. An island in the new banana jungle, United Fruit donated this site several decades after acquiring these lands.~ ~ ~

I turn back following the rusty rails into the heart of the finca. Yellow flowers and grass cover the rotting wood ties. Banana fields dense on either side.I soon come upon a light-ochre structure: PLANTA 22 – WITH TEAMWORK WE HAVE SUCCEEDED IN PRODUCING BANANAS OF THE BEST QUALITY DEL MONTE.

The sound of water and voices echo from the open building. The packing plant is idle until day after next when the banana branches will arrive on those cable lines. Their wire-mesh baskets hang empty.

But still the workers toil their seven days a week, from sunrise to after sunset. Barefoot women scrub the tanks in which the choice bananas are washed and disinfected. They scoop the water out of the vat with their hands and brush the rims and outside walls. A young boy helps his mother. The smell of their chemical bath hangs in the humid air. Empty Del Monte boxes stack. A woman rubber cements bright yellow plastic on blocks of styrofoam. They will divide the boxes, protect the fruit when packing resumes.

Outside, an empty truck waits, its rear doors open, to take the rejects to Central American markets. The conveyor belts to carry that clean, perfect fruit lie slack.~ ~ ~ ~

Again I walk atop the railroad barranca. A man in a short-sleeve t-shirt straddles the walls of an irrigation ditch. He turns the massive black wheel handle. Stagnant water seeps then flows into the field. A dirt road leads to grid-laid tin-roofed, smooth-plastered walls of the workers’ housing.

A blue tractor pulls a flatbed trailer. On benches sit four bananeros going into the fields.At the low bridge before Quiriguá village, the banana forest ends, and just at the edge of that pueblo, a yellow and black guard gate blocks the old tracks: HALT.

This branch off the Puerto Barrios line continues into the village of sagging wooden houses straddling canals. The tin roofs rust under the stormy sky.

Lorraine Caputo is a wandering troubadour whose writings appear in over 300 journals on six continents, and 22 collections – including On Galápagos Shores (dancing girl press, 2019) and Chaco Dreams (Origami Poems Project, 2022). She also authors travel narratives, with works in the anthologies Drive: Women’s True Stories from the Open Road (Seal Press, 2002) and V!VA List Latin America (Viva Travel Guides, 2007), as well as articles and guidebooks. Her writing has been honored by the Parliamentary Poet Laureate of Canada (2011) and thrice nominated for the Best of the Net. Caputo has done literary readings from Alaska to the Patagonia. She journeys through Latin America with her faithful knapsack Rocinante, listening to the voices of the pueblos and Earth.

Follow her adventures at www.facebook.com/lorrainecaputo.wanderer or http://latinamericawanderer.wordpress.com.

Synchronized Chaos October 2022: A PAN-LATIN AFFAIRE *

by Synchronized Chaos Guest Editor Lorraine Caputo

From mid-September to mid-October, Hispanic / Latinx Heritage Month is observed, celebrating the culture and history of Spanish-speakers of either side of the ocean, in Europe and in the Americas.

This month starts off with the observances of the independence from Spain of the Central American Republics – Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica – on 15 September, and Mexico’s Independence from that colonial power on 16 September. Chile celebrates its Independence and Fiestas Patrias on 18 and 19 September.

Also during this month – on 12 October – is the former Columbus Day, observed in Spain, Italy and the Americas. Now this date has different names in recognition of the Indigenous nations that populated the Americas before the 1492 Spanish invasion: Día de la Raza (El Salvador, Uruguay), Día de las Culturas (Day of the Cultures, Costa Rica), Día de la Resistencia Indígena (Day of Indigenous Resistance, Venezuela), Día de los Pueblos Originarios y el Diálogo Intercultural (Indigenous Peoples and Intercultural Dialogue Day, Peru), and Día del Respeto a la Diversidad Cultural (Day of Respect for Cultural Diversity, Argentina).

Synchronized Chaos’ Hispanic / Latinx Heritage Month literary feast also invites the other Latin cousins – French, Italian, Portuguese-Brazilian, Romanian, Catalan – to participate.

So, come join our party! ¡Buen provecho!

In his delightful short story “Mabel’s Library,” Fernando Sorrentino portrays the love of reading and of one’s personal book collection, in both life … and death.

In “Why (Do) White French Institutions Have a Hard Time Admitting The Impact Of Racism/Colonialism In Black Serial Killers’ Psychological Damage?: The Case of Thierry Paulin”, Victoria Kabeya asks a question that is common in this “post-colonial / post-racial” world, that [former] colonial powers proclaim – whether it be France, Spain, Portugal, Britain, the US, or …

Gabriella Garofalo’s “Blue Scenes” is a suite of poems woven with blue and so many colors of lives and their trails / travails. (Read this poem aloud – the rhythm will carry you …). In “Flames in the Wind”, Andrea Soverini captures the spirit of what is life – a perfect allegory for the upcoming Día de los Muertos.

The duality of what heals us – yet poisons us is presented in Diosa Xochiquetzalcoatl’s poem, “Café de la Olla.” Meanwhile, with his pair of poems, Roberto Rocha invites us to his barrio to witness the contradictions that are the “American Dream,” and the realities versus the stereotypes of what a Chicanx is.

With his essay “When the Stars First Came Out – Carmen & Bidu,” Josmar Lopes recounts the life and fame of two great Brazilian singers: the lovely Bidu Sayão, who is virtually unknown in the United States, and the electric Carmen Miranda, who became a Hollywood star.

In “Ballad of the Checkboard”, Ana M. Fores Tamayo asks who should be stepping back – the white or the brown-skinned, pawns in a chess game dictated by a white judge. “Fishing in the Green” is a surreal landscape of different lives / lifestyles existing parallel. “Matrimony” is a celebration of love. In “The Three Fates” / “Los Tres Destinos,” Fores Tamayo meditates on the passing of time … and life.

Despite her mother’s well-founded misgivings, Linda S. Gunther gets to see her father once again, at least for a short while. This “Rockefeller Center Reunion” is a story that is well-known by many children of divorced families.

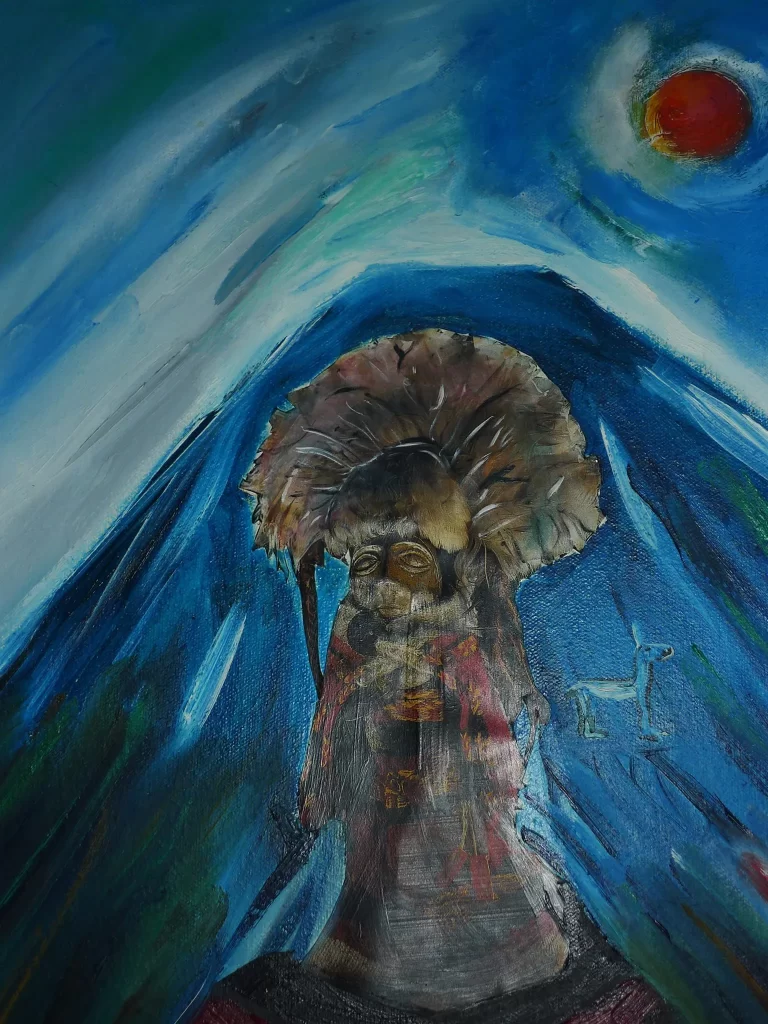

Diana Magallón‘s trio of images portray dancelike movements across multiple dimensions – trompe l’oeil (trick of the eye), hieroglyphics, and 3-D syncopations quiver with indigenous flair. Magallón and Jeff Crouch then offer a quartet of images that dispel the smoke of “100 Días de Humo” (100 Days of Smoke).

Does dancing cause one to fall into an everlasting love? Daniel de Culla answers that question for us in his poem “El Bailaré” / “The I’ll Dance.”

* This edition was inspired by the work of Fernando Sorrentino as well as the principle of Pan-Latinidad.

Poetry from Lorraine Caputo

WASHES I stretch out across the white-sheeted bed in my sea-colored room dappled with filtered sunlight I fall asleep, Don Quijote’s spine splayed above my head & I awaken to the sound of rain I peer through the open wooden slats of my window The sky is solid white with low clouds laying upon the sea grey & rolling, rolling white Thunder tumbles through this early afternoon This morning I sat out in the sandy courtyard to eat & could not I sat out here to write & could not I watched the white sun play tag with the clouds I wished it would rain, that it would so I could hide away within these blue walls where no-one could disturb me I feel like delving into this poetry to flesh out the sketches I have begun to give life to them I want to give birth to more & more poems But I am filled with hesitancy to hold my poems within these hands & to shape them My journal looms with its fleshless events Fear I may forget washes into me & I shrink away Then once more I expand to embrace the words & once more I contract A TOWN AWAKENING In the morning twilight, a pair of women washes dishes on a corner. Then one places the oilcloth over the tables where soon they’ll serve pupusas & coffee. She stacks the plates in the rack, recounts the silverware. The second checks the swelled corn before taking it to be ground. The beans are on the fire. A drunk stumbles & sways past on the other side of the road. In front of a shop, a man sweeps yesterday’s trash into the street. The broom’s swish is lost on the rumble of a passing bus. Pigeons swoop down from the tops of buildings. They peck along the ground. A skinny golden dog sniffs the garbage in the gutter. A graying-haired woman in experienced haste sets up her general store stand. The tarp overhang is stretched, items placed on shelves. A woman stops to buy eggs & sugar. A pick-up truck drives towards the market. Baskets & crates stack a-back, full of bananas, cabbage, tomatoes. Wood boards clank as they build make-shift stalls. Mangos & melons, green-topped onions & braided garlic mound. The rattle of a dolly, the groan & hiss of bus brakes, the laughter of men’s conversations. A radio is turned on somewhere. The sounds of this town awakening swell around the pupusa woman who sits, chin on hand, at one of the tables, waiting for her comadre to return from the mill. YEARNING THE SEA I. A child is crying when I fall into a visionless sleep … & I awaken in the dark to a voice & the perfume of a night flower my journey soon will continue wending, twisting from snowy mountains to warmer lands II. In this lower place the days grow thick with storms never to break the sky heavy the horizon hazed I long to hear the wash of rains all day, all night with a crisp explosion of thunder III. I need to journey once more in search of the rain the sea & in my fatigue as I await my near- midnight hour departure once more I smell the sweet perfume of some flower IV. This new day I awaken to flat, flat plains & nearer to another range alpenglow-bathed in the sunrise Still too far from the sea, the rain the thunder LISTENING This three-quarter moon brightens the paths & brush In the breeze of the lessening tide sway salt bush & muyuyo The night air washed with the constant whisper of waves washing upon worn lava & here I sit, listening to this night listening …

Lorraine Caputo is a wandering troubadour whose writings appear in over 300 journals on six continents, and 19 collections – including On Galápagos Shores (dancing girl press, 2019) and Escape to the Sea (Origami Poems Project, 2021). She also authors travel narratives, with works in the anthologies Drive: Women’s True Stories from the Open Road (Seal Press, 2002) and V!VA List Latin America (Viva Travel Guides, 2007), as well as articles and guidebooks. Her writing has been honored by the Parliamentary Poet Laureate of Canada (2011) and nominated for the Best of the Net. Caputo has done literary readings from Alaska to the Patagonia. She journeys through Latin America with her faithful knapsack Rocinante, listening to the voices of the pueblos and Earth. Follow her adventures at www.facebook.com/lorrainecaputo.wanderer or http://latinamericawanderer.wordpress.com.

Poetry from Lorraine Caputo

THE AZTEC EAGLE El Águila Azteca – Mexico City to Nuevo Laredo 27 January 1997 South of Tula we finally begin to escape the clutches of Mexico City’s smog The mountains are clearer winter gold speckled with dull green brush & cactuses A red-tailed hawk perches atop a budding tree Canyons sculpt the leached sandstone where dry arroyos wind like rattlesnakes We slow for a stretch where a train has derailed Metal power lines lay twisted The ages lava rocks, pale soil are charred Our locomotive hums as we pass by the workers repairing that other pair of tracks Broad-leafed nopales play patty-cake in the climbing sun ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ La Guega, Querétaro is where our train meets the Juarez-bound train continuing on its north-bound journey & we wait here listening to a barrel-chested man sing He rests the accordion on his paunch It waves like the sea between his broad, longer-fingered hands ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ At Escobedo, a woman stands on the platform twisting on tiptoes looking for her husband who’s inside this crowded train car She at last finds him & waves I’ll return soon he calls to her through the open window leaning over seats She nods & wipes away a tear with the edge of their infant daughter’s blanket Call, she yells putting thumb to mouth little finger to ear She smiles fighting painful tears The wife stoops to their toddler & whispers in her ear Then lifting her onto the other hip they wave good-bye to father She turns away with the children to stand beneath the overhang of the station roof Again she wipes a tear turning a bit from her husband’s view As the train pulls away, she smiles We’ll be fine, love & I see her tears shadow her face ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ In a field dozens of men & women sow seeds Down a dirt path a woman balances a bundle of long-cut reeds atop her head ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ I stand in the vestibule watching three locomotives pull of a long string of cargo cars They click by just feet away Our brakes hiss as we stop Like an old-time movie frames clumsily flowing from one to another I can see the village on the other side of that passing train ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ The sky is lightening with the coming of another morning overcast & dull Leaves dance in an approaching storm White stone crumbles off the eroding mountains outside Monterrey The sierra further north is fuzzed by fog - VOYAGING FROM VERACRUZ The rising sun goldens the open wooden doors of the station. In front is parked the old black & silver Engine Nº 9 with its coal car. The tarnished-brown station bell awaits to be clanged. Across the street, in the port, a large ship berths at a pier. Standing idle to one side, a leading crane flexes. Through this white & ochre cavern echoes the flight of two lost pigeons. On the other side of the gates separating lobby from tracks, a man sweeps the tiled platform with a wide push broom. People bound for Xalapa & Mexico City line up at Gate 5. Plastic tote bags, handles tied with a bit of string – large boxes carefully wrapped around & around with rope – small knapsacks all lie at feet. A mother holds her new-born child, covering its head with a thin flannel blanket. Next to her, on a duffel bag, sits her chubby-faced son. He stuffs a stick of gum into his mouth & another. His slightly slanted eyes squint at the pack in his hands. He stands up & offers a piece to his mother, then to abuelita. His tuft of black hair bobs as he chomps his gum. The boy walks away, pulling his sleeves over his hands & prances around the station. We are told to move to Gate Nº 4. Boxes & packs are shifted to the orders of the guard. & the young boy pulls his gum out of his mouth with plump fingers. El Jarocho arrives a half-hour late from Mexico City, amidst the blare of its locomotive’s horn. From its long line of cars – 2nd class, 1st class, sleeper & dining cars, its passengers rush towards the lobby. The young guard holds his automatic rifle off his right shoulder. His black pants are tucked into shiny black military boots, neatly laced. He commands us to form a single line, a single line. For the love of God, form a single line, I said. His hand rubs the stock. Suddenly he finds the gate opening out of his control, from the other side. He calls for our steady stream to have tickets in hand. The man before me shifts his box to one shoulder as he is stopped for his. Hurriedly I dig mine out of my pocket & the guard allows me to pass. People run the half-length of platform to where our cars await on Track Nº 5. They wobble under the weight of heavy bags & boxes, laughing at the insanity of the rush. & even I find myself picking up my gait to the closer car. Sunlight dodges the platform roofs & finds its way into my window open to the morning. In the engineless passenger cars on Track Nº 4, I see a man weeping the length, followed by another swaying a mop. On the other side of us clangs the bell of El Jarocho’s locomotive dieseling alone into the railyards, abandoning its red-striped blue cars. & on the platform between, a young cat ochre & white sits alone. - GHOST TRAIN (Santa Cruz to Yacuiba, Bolivia) I. Late afternoon I float on this train’s requiem Brush scrapes the sides of the car & occasionally reaches through my open window to quickly tap my shoulder II. From the vestibule steps I watch the twilight countryside blur by & listen to the swooshing of wheels But soon I must leave Death has taken a seat next to me in a toothless man chewing coca leaves III. In my hazed sleep ghostly history whorls in the dust of our journey Río Grande clatters by & the guerrilleros with Che Guevara watch my shadow head bob in rhythm of this train Spider-web curtains drape from electrical poles to the thick vegetation IV. In the new dawn a white calf bounds into an emerald forest powdered by our passage Within the billowing storm we raise the spirits of a hundred thousand soldiers still roam this bloodied soil of the Chaco V. We are nearing the end of our journey The bright seven-a.m. sun glints off a blue- graved cemetery nestled atop a hill

Lorraine Caputo is a wandering troubadour whose poetry appear in over 250 journals on six continents, and 18 collections – including On Galápagos Shores (dancing girl press, 2019) and Escape to the Sea (Origami Poems Project, 2021). She also authors travel narratives, with works in the anthologies Drive: Women’s True Stories from the Open Road (Seal Press, 2002) and V!VA List Latin America (Viva Travel Guides, 2007), as well as articles and guidebooks. In 2011, the Parliamentary Poet Laureate of Canada honored her verse. Caputo has done literary readings from Alaska to the Patagonia. She journeys through Latin America with her faithful knapsack Rocinante, listening to the voices of the pueblos and Earth. Follow her adventures at facebook.com/lorrainecaputo.wanderer or latinamericawanderer.wordpress.com.

Essay from Lorena Caputo

REVISITING A MEMORY

15 January 1994 / Estelí, Nicaragua

We gather in front of a blue bullet-pocked building near the central park. Women of the Madres de los Héroes y Mártires sell home-made plastic flowers. A late-afternoon summer wind blows.

Soon we are a procession, honoring the memory of Leonel Rugama. That seminarian, teacher, poet. The guerrillero who helped finance the Revolution by robbing banks. He and two compañeros were trapped in a safehouse. Surrounded by tanks, by hundreds of troops. For three hours the shooting went on. The planes bombed. That was 15 January 1970.

His petite and spry mother leads us to the cemetery. In song and conversation we go.

After a simple commemoration at his grave, we wander around the yard alone, in groups. The Mothers visit their heroes’, their martyrs’ tombs.

A professor from the States says to me, “Stop and listen. It is time to listen.”

His students find a series of turquoise crosses. The people all died about the same date. We are told they were victims of a Contra attack.

I feel chilled, hollow.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Almost four and a half years later, I return to face those graves that have haunted me.

Do they really exist? Was it a dream? No. I have the journal entry. What were the dates? Fourth to sixth of June 1987? Or ’86? I don’t remember.

It is a scorching late-dry-season day. For several hours I wander, trying to find those sea-blue markers.

I encounter Combatiente Juana Elena Mendoza’s site. She fell on the day of Liberation, 19 July 1979.

You walked without resting

the long road of liberation

with the recompense

of seeing your people

In Freedom

And I come across that simple white marbeline cross surrounded by a white wrought iron gate: Leonel Rugama R.

My memory remembers that sea to be to the right. But it is now crowded with newer tombs. I cannot find what I’m looking for.

I ask a grave digger, standing chest-deep in a fresh hole. He shrugs, “Go ask the pantonero.”

“Ah, yes. It is over there, to the right.”

Again, I do not find those 30, 40 turquoise crosses. I give up. For today.

“No, he’ll show you there,” the caretaker says, nodding to an assistant.

I am lead to a section of simple concrete crosses, and of tiled ones. Of blues, yellows, greens. Of combatientes, subtenientes, tenientes, sargentes.

I spend several hours more, copying the names and dates of these 57 heroes. They fell in battle against the US-Contras between 16 October 1983 and 8 January 1985. The majority in those two Octobers, Novembers, Decembers. Four in July 1984—the time of Congressional budget hearings, no?

First Sergeant Sixto A. Moreno did not see 1984 arrive. Subteniente José Angel Calderón Ordónez fell on Nochebuena—the Good Night—Christmas Eve. Ramón Arier Rizo Castillo died a week after his 19th birthday.

But I know this isn’t what I witnessed four years earlier.

The doubts, the uncertainty gnaw at my mind. After several weeks, I go back to Estelí and ask several Mothers.

I went to look for it, but I can’t find it. The workers showed me to the Armed Forces section. But it isn’t what I remember.

“Do you know of such a place?”

“It must be that common grave,” one says leaning in her chair.

“Yes. They were all victims of a Contra attack,” the other says, running her hand over the counter.

“There’s a common grave?”

“Yes.”

“There’s another one, too, in Cemeterio El Carmen. A mass burial of combatants of the April Uprising,” the second informs me.

“During the Insurrection,” the first clarifies.

I ask myself out loud, “Could that common grave have been disappeared by those newer ones?”

The Mothers look at one another and shrug.

But still, my memory remembers not one marker. It still sees so freshly a wash of 30 or 40 turquoise crosses.

I return to that part of the cemetery and widen the circle. More groupings of dates I’d missed before, among the newer sites of this decade.

There’s a tall, blue-brick pedestal with a black iron cross:

MARIO RANDEZ CASTILLO

4 February 1988

The bullets of the Contra assassins

may have killed you

But they did not kill your faith

The rain drizzles. The dripping weeds are slick. The earth is soft.

Still I cannot find them.

I ask Rugama’s cousin, who works here. “Ask the pantonero.”

The caretaker does not know. He swears there is no common grave. He asks the Rugama.

“Look, we’ve both been here only a few years,” the cousin apologizes.

The pantonero points to the western part of the yard, the opposite direction from the others. “Over there are burials from the same era. Perhaps it’s there.”

In the petering rain I enter the sea of crosses. Into 1985. Soon their dates group. Scattered here and there are combatientes, first lieutenants.

There are so many dozens from May 1985. How many just between 17th and 19th? One, two, three, six.

I weave back and forth through.

Another group: 2 to 7 August. One, two, four—again, six.

I climb between the closely packed graves.

Silvio A. Chavarría Méndez—fell in defense of the fatherland in Miraflores, Estelí, 20 May 1986. And entombed next to him are more people killed on that same day. Three from the Talavera family.

Oh, god.

I continue wading through these mostly blue crosses, scanning them for dates.

28 July 1985—so many, it seems. One, three, six, eight—nine.

I begin to swoon, ready to vomit. My solar plexus is hollow. I almost sink to my knees.

This is it. I remember this feeling. The same I had four years ago.

I want to stop. But I continue strolling through this jumble of graves.

How many died 7 September 1985? In May ’86?

I want to scream, “How could you do this?”

How many hundreds of graves are there? I dare not count.

How could we do this?

And those velvet storm clouds rumble overhead. A chill wind blows. The sprinkled rain has stopped—for a while.

Lorraine Caputo is a wandering troubadour whose poetry appear in over 200 journals on six continents, and 14 chapbooks – including Caribbean Nights (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2014), Notes from the Patagonia (dancing girl press, 2017) and On Galápagos Shores (dancing girl press, 2019). She also authors travel narratives, with works in the anthologies Drive: Women’s True Stories from the Open Road (Seal Press, 2002) and V!VA List Latin America (Viva Travel Guides, 2007), articles and guidebooks. In 2011, the Parliamentary Poet Laureate of Canada honored her verse. Caputo has done literary readings from Alaska to the Patagonia. She journeys through Latin America with her faithful knapsack Rocinante, listening to the voices of the pueblos and Earth. Follow her adventures at facebook.com/lorrainecaputo.wanderer or latinamericawanderer.wordpress.com.