The Mouth Is Dreaming

SIBYL

William Kentridge and collaborators

Zellerbach Hall

Berkeley

A review by Christopher Bernard

The climactic event of an academic-year-long residency at UC Berkeley by the celebrated South African artist William Kentridge, was the United States premiere at Cal Performances of SIBYL, the latest example of his deeply witty, darkly lyrical, postmodernly brilliant, if intermittently satisfying (though the two last qualifiers are perhaps redundant), but exhilarating suspensions in organized theatrical chaos.

Beginning as a reluctant draftsman, and having gone through a succession of dead-end careers in his youth (as the artist has described in interviews), Kentridge finally embraced the fact that his deepest gift lay in drawing; in particular, his capacity to turn charcoal and paper into an infinite succession of worlds through the dance of mark, smear, and erasure, similar to those of a master central to him, Picasso. Through drawing, he was able to extend his explorations into other fields of interest, including sculpture, film, and theater, above all opera and musical theater, attested to by his celebrated productions of operas by Berg, Shostakovich, and Mozart.

The artist also realized that it was precisely this capacity for creation itself – though perhaps a better term for it might be perpetual transformation – that stood at the heart of what we must now call his peculiar, and peculiarly fertile, genius (a term I do not use lightly – Mr. Kentridge is one of the few contemporary artists whom I believe fully deserves the word).

The latest hybrid work combining his gifts is a theatrical kluge of disparate elements that meld into a uniquely gripping whole, though there are gaps in the meld I will come to later.

The central idea is the Cumaean Sibyl, best known from Virgil’s Aeneid and paintings by Raphael, Andrea del Castagno, and Michelangelo. A priestess of a shrine to Apollo near Naples, she wrote prophecies for petitioners of the god on oak leaves sacred to Zeus, which she then arranged inside the entrance of the cave where she lived. But if the wind blew and scattered the leaves, she would not be able to reassemble them into the original prophecy, and often her petitioners would receive a prophecy or the answer to a petition not meant for them, or too fragmentary to be understood.

The performance opens with a film with live musical accompaniment, called The Moment Is Gone. It spins a dark tale of aesthetics and wreckage involving the artist in witty scenes with himself as he designs and critiques his own creations (a key link in his own transformations), and, in two parallel stories, Soho Eckstein (an avatar of the artist’s darker side who frequently appears in his work), a museum modeled on the Johannesburg Art Gallery, and the Sisyphean labors of zama zama miners – Black workers of decommissioned diamond mines in South Africa; work that is as dangerous and exhausting, and often futile, as it is illegal. Leaves from a torn book blow through the film bearing Sybilline texts: “Heaven is talking in a foreign tongue,” “I no longer believe what I once believed,” “There will be no epiphany,” and long random lists of things to “AVOID,” to “RESIST,” to “FORGET.” The museum is undermined and eventually caves in at the film’s climax, leaving behind a desolate landscape surrounding an empty grave.

The film is silent, though its exfoliating imagery almost provides its own music, an incessant rustling of forest leaves like those of the original Sibyl’s cave. The live music is composed by Kyle Shepherd (at the piano) and, by Nhlanhla Mahlangu, choral music sung by a quartet of South African singers, including Mr. Mahlangu. The choral music is based on the hauntingly quiet isicathamiya style of all-male singing developed among South African Blacks in eerie parallel to the spirituals of American Black culture, and for similar reasons: to try to console them for a seemingly inescapable suffering caused by white masters in a brutally racist society.

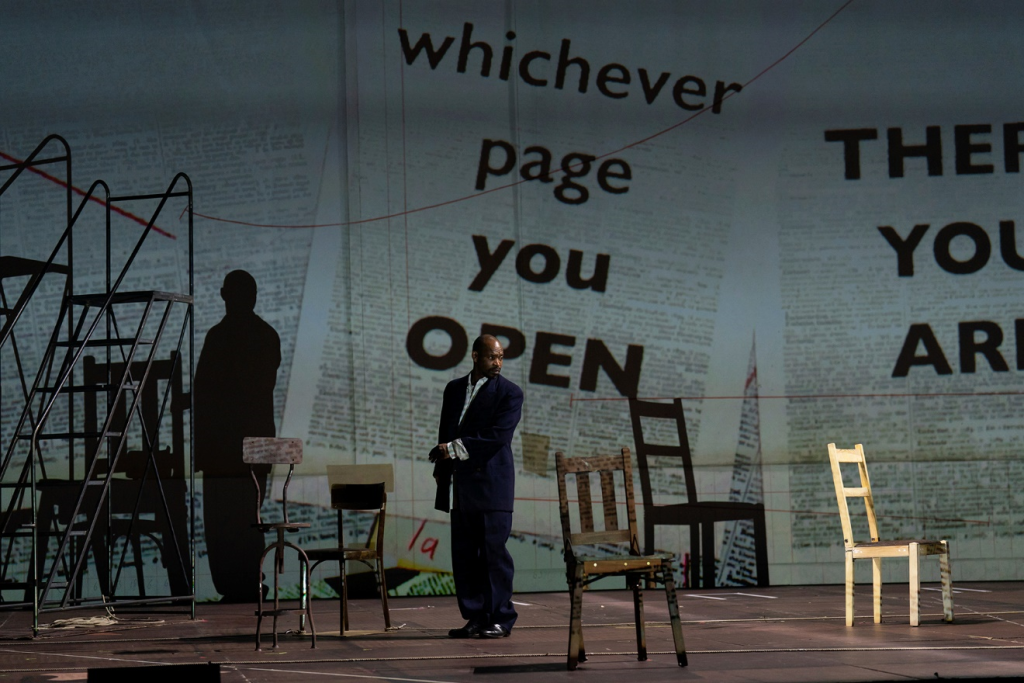

The second half is called Waiting for the Sibyl, in six short scenes separated by five brief films. The live portion presents half a dozen or more singers and dancers in scenes from the life of the Sibyl acting out her half-human, half-divine mission. Several of the scenes also incorporate film projections of drawings in charcoal and pen and pencil, black-ink splashes dissolving into mysterious exhortations (some of the visuals are powerfully reminiscent of Franz Kline’s black paintings on newspaper and phone directory pages from the 1950s), and Calder-like mobiles and stabiles, the most powerful of which spins slowly for several minutes, turning from an ornate display of stunningly dark abstractions into a climactic epiphany of resplendent order: the divine oakleaves of the Sibyl upon which we can read our destiny if we are lucky enough to find the one meant for us. The claim “There will be no epiphany” is here startlingly, and definitively, denied.

A line of bright lights along the front edge of the stage projects the shadows of performers and props against back screens and walls to effects that are both compelling to watch and symbolic of the dark side of every illumination. In several of the scenes, Teresa Phuti Mojela, playing the Sibyl herself, dances in magnificent passion as her shadow is projected grandly on the screen behind her to the right of which a flashing darkness of charcoal and ink from the artist’s hand dances beside her.

In other scenes, the treachery of the material order is allegorized in a dance of chairs moving apparently by themselves across the stage and collapsing just when a poor human being needs to rest on one from the unbending demands of the material order of living.

In another scene, a megaphone takes over the stage and barks orders across the audience, many of them transcriptions of the oracular pronouncements on the Sibylline leaves: “The machine says heaven is talking in a foreign tongue.” “The machine says you will be dreamt by a jackal.” “The machine will remember.” Though then the megaphone – stand-in for the machine – seems to turn against itself: “Starve the algorithm!” it demands, shouting over and over, to several unequivocal responses (“Yes!” “You said it!”) from the audience I was in.

One of the most dazzling of the short films is an immense one-line drawing that begins as a dense chaos of swirling squiggles in one corner that eventually builds into an elaborate, precise, wondrous, surreal but perfectly legible drawing of a typewriter. But the draftsman does not stop there, he continues drawing wildly, apparently uncontrollably until the screen is a thick liana, a fabric of chaotic twine, the typewriter slowly sinking beneath the chaos of a creation that cannot stop. This is a nearly perfect example of the perpetual transformation – one might say, of existence itself – that is one of Kentridge’s central themes.

SIBYL is filled with such brilliant and, for me, unforgettable moments, as I have learned to expect from this artist after he first invaded my mind in a retrospective I saw in 2010, and in the following years in such masterful creations as “The Refusal of Time.” But the piece is not without weaknesses. The artist admits, in interviews, that he does not know how to tell a story. And that is clearly true – and in most of his work, it doesn’t matter. But for a live performance, something like a narrative arc is required for a piece to cohere and satisfy at least this spectator. The arc can be as abstract as you please (such as in a Balanchine ballet), but it needs to be there. And it is not present in the second part of SIBYL (where it needs to be) nor, a fortiori, in the work as a whole. The production provides a fascinating evening, loaded with ore; my only complaint is that it could have been even better than it is. For example, I was expecting a fully climactic conclusion. There is none; it just stops. The ending is merely flat. Postmodernly unsatisfying.

Among the things that stay stubbornly in memory are the vatic sayings of the Sibyl herself, strewn across screen and stage as at the mouth of the priestess’s cave: “Let them think I am a tree or the shadow of a tree.” “It reminds me of something I can’t remember.” “We wait for Better Gods.” “The mouth is dreaming.” “Whichever page you open” “There you are.”

_____

Christopher Bernard’s third collection of poetry, The Socialist’s Garden of Verses, won a PEN Oakland Josephine Miles Award and was named one of the “Top 100 Indie Books of 2021” by Kirkus Reviews. He is a founder and co-editor of the webzine Caveat Lector.

Pingback: Synch Chaos April 2023: Wandering the Wilderness of the Soul | SYNCHRONIZED CHAOS

Thanks Chris for the vivid review. I feel like I was there in the audience. I can feel you lost compass at the end with no storyline to guide you. Beginning-middle-end can feel like an artistic straitjacket, yet one that artists ignore at their peril! LOL That “script” is, after all, the storyline of the human condition.

Oops, typo, meant “YOUR lost compass,” not “you”. Thanks