When the Stars First Came Out - Carmen & Bidu

AS THE YOUNG SOPRANO CONCLUDED THE LAST OF HER ENCORES AND WAS savoring the applause of an appreciative public gathered to hear her command performance at the White House in Washington, D.C., then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt enthusiastically approached the fragile-looking figure before him. Looking past the adoring crowd, FDR complimented Bidu Sayão on a most enjoyable concert program.

In the same breath, President Roosevelt casually proposed to the foreign-born singer an immediate American citizenship — most likely a calculated gesture on his part, motivated by his administration’s bold dedication to the upcoming policy of the “good Northern neighbor.”

Obviously flattered by her host’s generous offer, the gracious Bidu politely declined. “Thank you, Mr. President,” she was acknowledged to have replied. “But I am a Brazilian artist and would like to die as one.” The date was February 1938.

A little over a year later, on May 17, Broadway producer Lee Shubert, of the Shubert Brothers Theatrical Company, was preparing to greet another Brazilian artist, one whose ship had just pulled into Boston harbor, with her band, luggage, and retinue in tow. She was scheduled to make her U.S. stage debut, in Beantown, in Shubert’s 1939 musical revue The Streets of Paris, a show that featured the local appearance of comedy duo Bud Abbott and Lou Costello. The Brazilian artist’s name was Carmen Miranda.

Disembarking from the S.S. Uruguay, she was met by a horde of big-city newspaper reporters, all eager to record the spontaneous comments of this sizzling Latin sensation. Carmen did not disappoint them. Her first words to the waiting crowd were reported to have been, “I say money, money, money! I say twenty words in English. I say yes and no. I say hot dog! I say turkey sandwich and I say grapefruit… I know tomato juice, apple pie, and thank you.”

These two radically distinct responses, and seemingly unrelated occurrences, would come to denote to the Brazilian artistic community at large that, for a precious lucky few, living and working in North America — even while earning fame and fortune on her streets and in her theaters — would prove to be a most illusory pursuit. They would also serve to teach multi-talented Brazilian nationals some valuable life lessons in the world outside their native land; that the pains and compromises, glories and frustrations, triumphs and, ultimately, disappointments all such artists regularly endured for their art were no substitute for the loss of their individual identity.

To paraphrase a line from Rudyard Kipling’s poem “If,” rare were the artists that could keep their own heads, when all about them others were losing theirs. And there exist no finer examples of this than the stories of these two marvelous Brazilian singers.

Certainly, the old truism that “good things come in small packages” was never more so than in describing the physically compact yet vocally alluring attributes of the lovely Bidu Sayão and the electric Carmen Miranda. In reverse proportion to their small stature, they were the central figures in Brazilian opera and popular entertainment for the better part of thirty years.

Formally trained in Brazil and in Europe, and deeply influenced by Polish tenor Jean de Reszke and by her second husband, the Italian baritone Giuseppe Danise, Bidu Sayão was Brazil’s most well-known classical vocal export — and every inch an opera star of the first magnitude.

Although christened Balduína de Oliveira Sayão after her paternal grandmother (a name that she grew to despise), the singer would forever be known by the simple nickname of “Bidu.” Indeed, simplicity and restraint, in matters both personal and professional, were to become the hallmarks of her fame.

She was born on May 11, 1904, in Rio de Janeiro, to a socially prominent upper-class family, which relocated to the beachfront district of Botafogo when Bidu was but four years old. Tragically, her father died shortly thereafter, thus depriving her of a masculine role model and leaving the poor girl to her own juvenile devices.

Playful and tomboyish, with a unique flair for fun and mischief, the incorrigible Bidu was never to attend public school with the other children of her age group; she was instead to receive private tutoring at her mother’s home up through the age of sixteen. But the independence and resourcefulness she first exhibited in her youth would later manifest themselves on the operatic stage in many of her most memorable comic parts, specifically those of Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro, Adina in The Elixir of Love, and Rosina in The Barber of Seville.

Soon after her father’s untimely demise, Bidu’s older brother would assume his rightful place as the family patriarch, but the real seat of power would always remain with her sainted mother, Maria José. Significantly, the absence of a strong male figure in her formative years may well have been one of the root causes of Bidu’s early marriage to a man three times as old as herself.

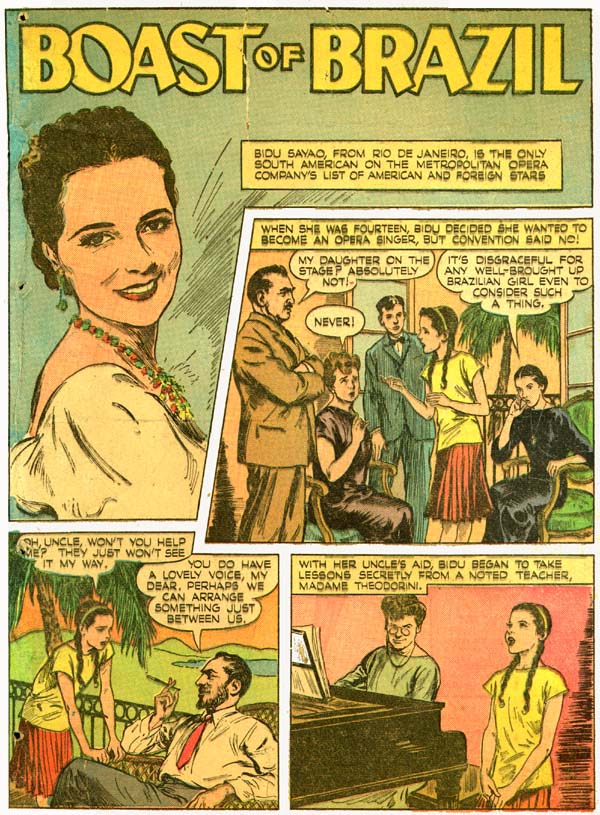

Yet even before this situation came about, the choice of a theatrical profession for a society debutante from Rio de Janeiro (she had thought about becoming an actor or a concert recitalist) was much frowned upon at the time by the privileged upper stratum. Recalling the event some years later, Bidu commented that, “Going on the stage was absolutely out of the question for a girl born to a respectable family.” This aspect of her early life struggles was charmingly captured in a 1940s comic-book depiction of her life entitled Boast of Brazil (1). In it, the young fourteen-year-old is shown being scolded by her parents (the father’s death a decade before notwithstanding) about her “wrongheaded” career decision; and told, in no uncertain terms, how disgraceful it would be “for any well-brought up Brazilian girl even to consider such a thing.”

Not to be dissuaded, the typically resilient teenager pleaded with her uncle, Dr. Alberto Costa, to take up her cause. As a result, the musically inclined Costa became instrumental in swaying the mother’s opinion about a potential singing career for her daughter, having earlier arranged for his niece to take private lessons from Romanian soprano Elena Theodorini, a former star of La Scala — who personally thought the girl too immature, and the voice too small, for such a serious undertaking.

Nevertheless, Bidu persevered. With patience, practice, and stubborn persistence, she managed to survive Theodorini’s rigorous voice sessions. This led to her informal 1916 debut at Rio’s Theatro Municipal in the Mad Scene from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, an appearance that would permanently put to rest the question of a career in the theater.

Theodorini’s resolute decision in 1918 to retire from teaching and return to her native country coincided with the end of the First World War. It also gave cause for the adventurous Bidu to accompany her instructor back to the European mainland, the first time the blossoming prima donna had ever been away from her close-knit family. Not to fear, as her mother Maria José stood close by as a chaperone throughout her years there. According to Bidu, “As time went by, my mother adjusted herself to the fact that there was no real stigma attached to opera singers, having met many charming ones.”

Moreover, the time she spent abroad was indeed fruitful. With the aid of various individuals in strategic places, Bidu applied for and was admitted to Jean de Reszke’s famed vocal school in Nice, France, where she was the only one of his personally handpicked pupils to have hailed from Latin America. The still elegant Polish tenor had been a principal lead with New York’s Metropolitan Opera Company long before Caruso’s debut there; and was a fixture at the house for many years prior to his own retirement in 1904. He would be the next to take on the role of surrogate father to the Brazilian novice, helping to refine and perfect her diction, and instructing her in the long-lost art of French singing style and vocal technique:

"De Reszke had an extraordinary ability to evaluate the text, integrating it to the music until they became one. This was to be of enormous help to me when I took on many of the Debussy scores. I never sang the role of Ophelia in Hamlet by Thomas, but her dazzling mad scene, which became a must on my concert programs, became a real part of me, so many were the times he made me go over it, concentrating on the words’ essence and producing sounds that would enhance them."

After the death of de Reszke in 1925 and Theodorini’s own passing the year after, Bidu was forced to seek assistance elsewhere in planning for her operatic future. With her mother’s permission, she journeyed to Italy for the express purpose of establishing contact with former diva Emma Carelli and her husband, the impresario Walter Mocchi, whom she had previously heard about while living in Brazil. Together, the couple ran the Teatro Costanzi (later changed to the Teatro Reale) in Rome, and, since 1910, Mocchi had also been responsible for the opera performances at Rio’s Theatro Municipal, as well as the fall seasons at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Mocchi took quite a fancy to the young Brazilian beauty, as did his soprano wife. Suitably impressed by the little songbird’s talents, Signora Carelli referred her to Italian maestro Luigi Ricci for training in operatic repertoire; and, on March 25, 1926, Bidu Sayão made her European debut at the Costanzi as Rosina in The Barber of Seville, later adding Gilda in Verdi’s Rigoletto, Carolina in Domenico Cimarosa’s Il Matrimonio Segreto (“The Secret Marriage”), and Elvira in Bellini’s I Puritani to her growing list of stage roles. Her success in the Italian capital soon paved the way for Bidu’s triumphant return to the Brazilian one: she reappeared in Rio de Janeiro, as Rosina, Gilda, and Carolina, in July of that year.

In the meantime, Mocchi had gone ahead and booked her for several more seasons at the Theatro Municipal in São Paulo, where he had accepted the management’s offer of a full-time directorship. Bidu went on to perform there in a variety of works, including fellow Brazilian Carlos de Campos’ Um Caso Singular (“A Singular Affair”) and the opera Sister Magdalena (1926) by, of all people, her uncle Alberto Costa, a sentimental payback of sorts for his having served as the family intermediary ten years prior.

How much Mocchi’s new position had to do with the singer’s extended local engagement, however, is not known, but it soon became a situation ripe with romantic speculation. Irrespective of the rumors that might have been generated by the physical proximity of these two individuals, fate would inevitably thrust them even closer together.

Mocchi and Carelli separated sometime before 1927, when he and Bidu took up their relationship. Then, in August 1928, Emma Carelli was involved in a fatal car accident in Italy. Her sudden death left a personal void in the busy professional life of Walter Mocchi, who now looked to Bidu for consolation. It would be easy to suggest that her subsequent 1929 marriage to the much older Mocchi was a relatively stable one, but the enormous forty-year difference in their ages proved a difficult gap for Bidu to close. She later admitted her mistake, claiming: “I have always searched for my father in the husbands that I married.” They, too, separated after a time, and were finally divorced in 1937.

Bidu would at last meet her prospective soul mate in the person of Italian opera star Giuseppe Danise. It was during a 1935 performance of Rigoletto at the San Carlo Opera House in Naples, quite possibly in one of the many moving numbers they had so often sung together at rehearsal, that soprano and baritone decided to transform their budding emotional relationship into a permanent love duet. The couple officially tied the knot in 1947 and would remain constantly devoted to each other until Danise’s own departure from this world on January 4, 1963. He was twenty-two years her senior.

Amazingly enough, Bidu Sayão was a close contemporary of another popular Brazilian entertainer: the exceptionally gifted and vibrantly captivating Maria do Carmo Miranda da Cunha, better known by her professional moniker as Carmen Miranda.

Born in the town of Marco de Canavezes, district of Porto, in Portugal on February 9, 1909, Carmen came to Brazil, along with her mother and older sister Olinda, when she was not yet one. She grew up in the city of Rio de Janeiro, at about the same time that Bidu was learning to climb trees in her backyard. Her parents dubbed her “Carmen” (thanks to her music-loving uncle, Amaro) in honor of the Spanish protagonist made famous by Bizet’s opera, or so the story goes. Otherwise, her connection to the art form was minimal, if nonexistent.

She was not, as some of the early publicity about her indicated, the offspring of a well-to-do family. Quite the contrary: her father, José Maria Pinto da Cunha, who arrived in Brazil ahead of his loved ones, had no discernible profession, although his background as a farm hand apparently telegraphed his low-born status. His main sideline, however, was as a barber (paradoxically, not of Seville). Out of necessity, her mother, Maria Emilia, became a laundress in Rio. She later managed a boarding house in the city, all to make ends meet. But whatever the family’s financial condition had been, the naturally plucky and irresistible personality that characterized the young Portuguese immigrant was already in evidence. Little Carmen left no doubt as to what her future aspirations might be: She would tell anyone within earshot that she was predestined by the entertainment gods for a career in the movies.

Like most working-class youngsters in Brazil at the time, Carmen was forced to quit school at an early age to go into the business community, holding down a variety of menial low-paying jobs, including one as a chatty hatmaker, and another as a “singing” store clerk, which resulted in her being verbally chastised by her boss for deliberately distracting her co-workers.

Luckily for her (and for the Brazilian labor market), Carmen was snapped up by the local radio stations, among them the widely heard Rádio Mayrink Veiga, after simultaneously cutting her first records for the Brunswick label in September 1929. Her first major hit was the march tune, “Taí, eu fiz de tudo pra você gostar de mim” (“There, you see? I did it all to make you fall for me”), recorded in January 1930.

She eventually landed a contract with RCA Victor, later with Odeon-Brazil and American Decca. Other song numbers followed in quick succession, including the best of such acknowledged songwriters as Assis Valente, Lamartine Babo, Joubert de Carvalho, André Filho, and Synval Silva. Her large, recorded repertoire of popular songs, ditties, march tunes, sambas, tangos, and other more obscure material from the period would reach into the literal hundreds.

Some revisionist authors have tried to describe her early singing style as a carioca version of Elvis Presley — that is, of a poorly educated white person with a modicum of musical talent, who happened to have incorporated the soul and substance of West African black descendants into her entertainment vocabulary and, in the process, made them virtually her own.

While the jury may be out on Elvis, it was an unfair indictment in the case of Carmen Miranda. In the first place, she was neither poorly educated or untalented, nor was she a “pale” imitator of a prevailing ethnic trend; and, in the second, the growth of marcha, chorinho, maxixe, and modinha — and especially samba during Carnival time — had already spurred many of Brazil’s native-born talents to write down and interpret these myriad forms as far back as 1915, most strikingly by composers Ernesto Nazareth, Francisca “Chiquinha” Gonzaga, Pixinguinha, and Heitor Villa-Lobos, to name only a few; and still later by the likes of Noel Rosa, Ary Barroso, João de Barro, and the Bahian-born Dorival Caymmi. Carmen’s particular genius was in taking the basic raw material found in this multitude of musical styles and thoroughly reinvigorating the form: by applying to it her unique blend of crystal-clear vocalism, rapid-fire verbal patter, and razor-sharp rhythm. This would ultimately lead to her creation of a black-white composite of the streetwise baiana figure, an endearing (and somewhat stylized) cultural by-product of Northeastern Brazil, one that was accessible to even the most sophisticated of theater-going audiences.

She would embellish this character further in her later domestic and Twentieth Century-Fox film work, but for now she strived hard to concentrate on her nightclub routines with younger sister Aurora, an equally talented sibling with artistic aspirations of her own. The two of them would appear frequently throughout the 1930s at the Cassino da Urca in Rio, usually backed by the Bando da Lua (“The Moon Bunch”) combo and other guest performers.

Such bubbling effervescence as Carmen seemed to exude should have been a veritable shoe-in for the budding Brazilian film industry; and true to form, she soon appeared in her first feature, the documentary O Carnaval Cantado de 1932 (“The Carnival Sung in Rio in 1932”), although she herself sang in only one musical number, “Bamboleô” by André Filho. A Voz do Carnaval (“The Voice of Carnival”) was released the following year, along with several other titles: Alô, alô Brasil (co-starring Aurora) and Estudantes (“Students”), featuring popular radio singer Mario Reis, both from 1935; Alô, alô Carnaval (1936) with an all-star cast headed by Francisco “Chico” Alves, Dircinha Batista, and Barbosa Júnior; and the mega-production Banana da Terra (“Fruit of the Earth,” 1939), where Carmen introduced moviegoers to her now-familiar Bahian alter ego.

All if not most of the examples cited above of early Brazilian cinema have been lost or, more correctly, have deteriorated over the years due to detrimental exposure to the elements. Only a small fragment of Banana da Terra remains. It depicts a youthful Carmen Miranda, surrounded by striped-shirted male dancers from the Cassino da Urca, in composer-lyricist Dorival Caymmi’s song, “O que é que a baiana tem?” (“What does the Bahian have?”). Carmen took her cue (along with the design and makeup of her costume) from the number’s lively lyrics, which describe the native Bahian’s outfit and accessories in excruciating detail

What does the Bahian have?

What does the Bahian have?

A torso of silk she has (yes)

An earring of gold she has (yes)

A necklace of pearls she has (yes)

The finest of jewels she has (yes)

A gown made of lace she has (yes)

A bracelet of gold she has (yes)

Her dress is superbly pressed (yes)

Her sandals the very best (yes)

And charm like no other has

So like the baianas have

(English translation by the Author)

During one of her many flamboyant performances at the Urca, the legend goes that visiting American impresario Lee Shubert became smitten with young Carmen at first sight and decided to hire the flashy entertainer “on the spot” for his Broadway mounting of The Streets of Paris, to premiere in New York in the autumn of 1939. In fact, Shubert had been receiving frequent communiques about her talent for many months prior to his actual arrival in Rio de Janeiro. Nevertheless, what he saw on the evening of February 15, 1939, at the Cassino da Urca nightclub, convinced him that previous reports of her extraordinary abilities had not been exaggerated (even if he understood little of what was being sung).

The stage was now set for the Hollywood phase of Carmen Miranda’s showbiz career — a midstream course correction neither as readily accepted, nor as openly welcomed, by fellow Brazilians as her “O que é que a baiana tem?” period had been.

That most formidable of early twentieth-century classical musicians, Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini, would once again influence the course and direction of Brazilian opera (that is, in a manner of speaking) by his fortuitous intervention in the burgeoning North American career of soprano Bidu Sayão. There exist several versions of their fabled encounter; but suffice it to say that the notoriously demanding maestro may have been moved by the Brazilian singer’s sensitive portrayal of the consumptive Violetta Valéry in Verdi’s La Traviata (which she first sang in Brazil), given in the mid-1930s at Milan’s historic Teatro alla Scala, where Toscanini once served as musical director.

The conductor had been looking for “a special, ethereal voice” for some time. At a formal reception for the diva in early 1936, at Town Hall in Manhattan, maestro Toscanini introduced himself to Bidu, and, while reminiscing about her La Scala appearances, he immediately piqued her musical interest in a work she had not previously performed in: French composer Claude Debussy’s poetic cantata, La Damoiselle Élue (or “The Blessed Damozel”), originally written for heavier dramatic soprano, a voice category the normally stratospheric coloratura was unaccustomed to singing in. Undaunted by the challenges inherent in this offbeat proposal, Toscanini offered to coach la piccola brasiliana in the difficult piece. He even recommended an alternative higher key for her comfort, for which he likewise supplied a revised vocal score:

I am sending you the high notes that I think ought to be suitable. They aren’t difficult because they more or less follow the orchestra’s melodic line. You are a good enough musician to adapt immediately to these few changes. With my most cordial greetings, Arturo Toscanini

Needless to say Bidu was hooked by this rare chance to work with the notorious Italian taskmaster, and willingly swallowed the bait. With the experienced hand of Arturo Toscanini leading her and then-mezzo (later soprano) Rose Bampton, and the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, along with the New York Schola Cantorum Singers at their disposal, Bidu Sayão made an auspicious Carnegie Hall debut in the Debussy work on April 16, 1936, to rave reviews in the press:

Sayão captures the plaintive, mysterious atmosphere of LA DAMOISELLE ÉLUE. Conveying the purity of the vocal line, the innocence of the character, and the tenderness of Debussy’s setting of Rossetti’s poem, Sayão is an ideal interpreter of this music. Toscanini referred to her singing as “just like a dream, an angel, from the sky.”

[Her voice], if light, was one of pronounced sweetness; silky and caressing when used at its best.

Taking advantage of the increased exposure these Manhattan concerts had provided, Bidu spent the next several seasons commuting to and from her native Brazil, and her soon-to-be-adopted North American homeland. “It was Danise who was totally responsible for my American career,” she insisted. “In 1936 he persuaded me to accompany him to New York and he introduced me to Signor Bruno Zirato, who [had been Caruso’s private secretary and] was very influential at the Philharmonic.” In the meantime, Bidu gave innumerable performances on both continents, but paid particular attention to Brazilian shores, by some accounts appearing in as many as two hundred different locations spanning the length and breadth of the country.

Upon her return to the States, the board of the Metropolitan Opera, at Toscanini’s insistence (and through the machinations of Signor Danise, who “knew his way around, for he had appeared over four hundred times at the Metropolitan”), tapped the busy soprano to make her debut in a part not generally associated with South American artists: that of Jules Massenet’s wholly and beguilingly Gallic young heroine, the beautiful and coquettish Manon Lescaut.

Although he himself no longer had any direct involvement in running the company, maestro Toscanini nonetheless proved relentless in persuading the Met Opera’s stodgy management to take on the Brazilian nightingale for this plum assignment — even though Manon went far beyond the kind of limited vocal fireworks Bidu was then capable of producing, nor was it yet a regular staple of her core repertoire.

Fortunately for the Met, the singer had been slowly expanding her roster of parts to encompass the more lyrical aspects of such roles as Violetta in La Traviata, Juliette in Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette, and Mimì in Puccini’s La Bohème, even before she had met her second husband, Giuseppe Danise. It was to Danise’s credit, therefore, that he was able to confidently guide his young protégée along this productive path and stretch her usual list of comical soubrette parts by including more “dramatic” vocal opportunities. Admittedly, this opened up fresh avenues for Bidu to explore, now that she had been performing ad infinitum the same well-worn roles of Gilda, Rosina, and Susanna over the entire length of her career — even though audiences still flocked to see her in them.

With her authentic French diction and remarkable ability to breathe theatrical life into increasingly complex characters, Bidu was ideally poised to conquer the environs of North America, just as she had done in Europe and Latin America some ten years earlier.

Finally, on February 13, 1937, on a cold and wintry Saturday afternoon (a national radio broadcast, at that), the captivating thirty-two-year-old Brazilian diva stepped out from behind the golden curtain and into the warm glow of the stage at the old Metropolitan Opera House, on Broadway and Thirty-Ninth Street, to bask in a well-deserved ovation for her premier performance in Massenet’s opera Manon. She delivered what many of her staunchest supporters would come to regard as her most elaborately prepared, most fully realized, and most passionately heartfelt portrait to date.

In addition to the chilly weather, there was a last-minute cast change in one of the leads: that of her compulsive lover, the Chevalier des Grieux. “It was supposed to have been [Belgian tenor] René Maison,” Bidu recalled some years later for The New York Times, but it turned out not to be the case. “He was sick, but they didn’t tell me, because they didn’t want to make me nervous. So I stood looking and looking, and I was getting nervous [all the same] because I didn’t see him. Then a strange man greeted me! I almost fell down! When there was a [free] moment, he said, ‘Hello, I’m Sidney Rayner.’ I said, ‘I’m Bidu Sayão,’ even though I think he already knew that, and we went on from there.”

Notwithstanding the impromptu nature of the proceedings, the broadcast came off as scheduled. Manon would go on to become her third most requested role (twenty-two appearances in all) during her extensive Met Opera tenure, lagging behind only Susanna and Mimì (forty-six performances each), and Violetta (with twenty-three), in number of times sung.

It is noteworthy to point out that opera soprano Bidu Sayão had established a firm foothold on the legitimate Broadway stage two years and four months before Carmen Miranda was to do so; and a full three years prior to Carmen’s own footprints were to be permanently enshrined on Hollywood’s immortal Walk of Fame.

The High Price of Fame in Brazil

THEY BOOED. THE AUDIENCE HAD ACTUALLY BOOED. IT WAS UNHEARD OF, absurd, to say the least — yet it was true. But how could such a thing have happened in Rio, and, most distressingly of all, to Bidu Sayão, the operatic sweetheart of the Southern Hemisphere?

Five months after her earlier appearance at the Theatro Municipal, the stylish Brazilian singer’s debut at the Metropolitan Opera House had caused a major stir; it was labeled the surprise hit of the 1936-1937 season. “Miss Sayão triumphed as a Manon should,” wrote New York Times music critic Olin Downes of her mid-winter debut, “by manners, youth and charm, and secondly by the way in which the voice became the vehicle of dramatic expression.” “Any conjecture as to how Sayão’s small but perfectly produced voice would fare in the great spaces of the Metropolitan [was] speedily allayed,” raved Paul Jackson in Saturday Afternoons at the Old Met. “Her affinity for the French style…and a decade’s experience in European houses enabled her to set foot on the Met stage with a portrayal fully formed.”

The company chose Bidu to assume the repertory of the recently retired Spanish soprano Lucrezia Bori. And within weeks of her initial engagement, she was assigned the lead role of the consumptive Violetta Valéry in La Traviata, followed quickly by her first Mimì in La Bohème. “She was an unmatched Norina, Zerlina, and Adina,” continued Mr. Jackson. “Sayão’s Violetta is a vivid creation and exceedingly well sung throughout… She turns the coloratura of the first act into a dramatic device just as Verdi intended…”

With many U.S. opera companies on hiatus until the fall, that previous year (1936) Bidu had been free to enjoy the warmer waters of her tropical port city and its own extensive concert and opera-going season. Her ambitions there were modest, in the extreme: to please her many fans and admirers, as she had been doing for the past six seasons, at Rio de Janeiro’s Theatro Municipal.

She had lately appeared as Rosina in the opera The Barber of Seville. Bidu was also scheduled to sing Verdi’s Violetta, along with Lakmé in Delibes’ eponymously titled work, and, in honor of the one-hundredth anniversary of Carlos Gomes’ birth, the part of Cecília in Il Guarany. In prior seasons, Bizet’s Carmen had been a popular attraction, which once starred the celebrated Italian mezzo Gabriella Besanzoni, a past veteran of many a South American production of the work and a mainstay at the Municipal since 1918.

Described as “badly-behaved and impertinent” by the Met’s one-time director Giulio Gatti-Casazza, the high-strung Besanzoni had lucked into a society marriage with Brazilian industrialist Henrique Lage back in 1925. This tended to keep the temperamental diva anchored to the capital, with the Theatro Municipal serving as her homeport. Upon leaving the stage in 1939, Ms. Besanzoni turned to teaching to take up her spare time. As an instructor, it was widely rumored the Roman native was a superior judge of vocal talent — one of her prize pupils would turn out to be the carioca baritone Paulo Fortes.

In all, there was ample evidence to suggest the August 1936 performances of Gomes’ Il Guarany in Rio would be a far from routine affair, if not a fairly exciting one. What actually transpired onstage could not by any means be considered unexpected; but the passage of time, muddled individual motives, and even sketchier personal recollections have a way of blurring the finer details of how and why certain events took shape. The indisputable facts, though, were these: Unable to cope with Bidu’s recent string of successes, the feisty mezzo-soprano organized a demonstration by the members of her claque to boo the little prima donna into submission, and on her home turf. Besanzoni “had been a magnificent singer,” claimed Bidu, in a 1973 interview for Veja magazine, “the best Carmen I have ever seen. Although she was no longer performing, she was insanely jealous of anyone who appeared [at the Municipal].”

Besanzoni’s boisterous negative campaign fizzled, however, as the entire theater soon got wind of the plot. After Cecí’s moving act two ballata, “C’era una volta un principe” (“Once upon a time there was a prince”), the audience erupted into a steady stream of applause that purportedly drowned out the noisy offenders, who proceeded to beat a hasty retreat from the peanut gallery, Madame Besanzoni among them.

Badly shaken by the incident, Bidu was overheard to have declared that she would refuse all future offers to sing in Rio de Janeiro — and, for that matter, in Brazil, too. Despite claims to the contrary, the soprano rethought her earlier position and thankfully returned to her native land on several occasions near the end of the 1940s, appearing in La Bohème, Roméo et Juliette, Manon, and Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande. “In any case,” Bidu explained years later to Veja, “this was a minor incident, with little importance that I recall without a trace of anger because I have never been jealous of anyone.”

She gave her last complete performance at the Theatro Municipal in 1950, as Mimì in La Bohème; but after that painful Guarany she would most heartily concede to becoming a full-fledged member of the Metropolitan Opera’s roster of artists, the only one from South America.

Aside from the poor reception in Rio, there were other, more valid justifications for her decision to depart for “friendlier” Northern corridors, one of which was to be closer to Metropolitan Opera baritone Giuseppe Danise, the long-awaited love of her life; but the main reason was the volatile political situation of pre-World War II Europe.

For Bidu, this did not necessarily translate into a moratorium on her stepping onto Brazil’s stages, but it did pose a serious threat to anyone bound for European opera houses, regardless of national origin. As it was, the escalating global conflict had put a severe damper on most foreign classical pursuits, in essence restricting the coloratura and other paid professionals to the safer environs of North America for the duration of the conflict. Still, the sad truth remained that Bidu Sayão was hurt, and it showed in her avoidance of Brazil as a routine layover spot.

As for Besanzoni, she would stay noticeably closed-mouth on the subject of her actions on that particular evening. We can only speculate, at this point, as to her convoluted reasoning behind them. They had a lot to do with the perceptive singer’s suspicion of an unofficial snub by the Metropolitan Opera during the 1919-1920 season, a period in which she was asked to take on many of the same roles as the house’s resident work-horse, the stalwart Austro-Hungarian artist Margarete Matzenauer.

According to various accounts, Besanzoni became convinced that her Teutonic rival had somehow bribed the claque to despoil her every Met Opera appearance. Curiously, reviews from that time seem to corroborate this notion: There is a marked indication that an organized and clearly exaggerated favoritism for Ms. Matzenauer was at the heart of the anti-Besanzoni faction. And, in the Italian’s own blunt assessment of events, “the ‘German’ did everything in her power to prevent me from being hired by the Metropolitan.”

Her past ill treatment in the Manhattan press, plus the unfavorable reaction of Met Opera audiences, might well have gone a long way toward fanning the mezzo’s future flames of envy with regard to Bidu’s growing popularity. We may never know for certain, but Madame Besanzoni’s overly paranoid sensibilities do serve to explain some of the later green-eyed behavior attributed to her, and unreasonably extended to the tiny Brazilian warbler.

As bad as the experience of being booed in Rio’s Theatro Municipal may have been for Bidu, it was nothing compared to the cold shoulder offered by her own callous countrymen to Brazil’s cultural ambassador of the war years, the exciting (and excitable) Carmen Miranda.

The flashy entertainer’s runaway success on the New York stage during the 1939-1940 Broadway show seasons (her official “start date” was June 19, 1939) had only begun to whet the appetites of post-Depression era audiences starved for more novel and adventuresome theater fare. César Ladeira, one of Rio’s best-known radio announcers, also found himself in the Big Apple, broadcasting the remarkable news of Carmen’s triumphant debut on the Great White Way to all of Brazil.

Accounts from that period reported that traffic had stalled outside the Broadhurst Theatre where she was appearing. In fact, the streets were virtually clogged with noisy automobiles. Carmen and her band (which included a young musician named Aloysio de Oliveira, who became not only the up-and-coming star’s interpreter and spur-of-the-moment guide, but also her live-in lover) were huddled together at an all-night restaurant, waiting for the early edition of The Daily Mirror to arrive.

The first of the headlines pronounced producer Lee Shubert’s The Streets of Paris a dud, but it praised Carmen Miranda’s participation to high heaven: “A new and grandiose star is born who will save Broadway from the slump in ticket sales caused by the popularity of the New York World’s Fair of 1939,” wrote notoriously opinionated columnist Walter Winchell. Next, from John Anderson in the New York Journal-American: “Carmen Miranda stopped the show!” And then, from The New York Post’s Wilella Waldorf: “You could see the whites of her eyes from row twenty-five!” And from theater critic Brooks Atkinson for The New York Times: “The heat that Carmen generated last night may well blow out the city’s heating-and-air-conditioning system this winter!” The final, four-star banner, however, came from Earl Wilson of the Daily News: he proclaimed Carmen Miranda to be the “Brazilian Bombshell,” a nickname she would be stuck with for the remainder of her American career.

Indeed, Carmen’s initial Broadway outing segued directly into her U.S. film debut in the musical comedy Down Argentine Way, which starred Betty Grable and Don Ameche. Released in early 1940, this first of several Twentieth Century-Fox Technicolor productions featuring the exotic performer was an immediate smash hit with enchanted movie audiences. Initially, because of contractual commitments that included three or more shows a night, with brief runs to and from the New York World’s Fair and Shubert’s adamant refusal to let her leave for Hollywood, the studio sent a camera crew to New York in order to capture Carmen and Bando da Lua during a break in the action.

Whether she played Argentines, Cubans, Mexicans or Brazilians, movie fans clamored for more of Carmen Miranda; and the Fox Studios wisely obliged, signing the lively songstress to a generous six-figure salary (her clashes with lecherous studio head, Darryl F. Zanuck, were an awkward “highlight” of her years there); it would soon make her the highest paid female entertainer in the United States. “Hollywood, it has treated me so nicely,” Carmen was quoted as saying, “I am ready to faint. As soon as I see Hollywood, I love it!”

But just before her West Coast film career took off in earnest, Carmen and her Bando da Lua paid a return visit to Brazil — and to the Cassino da Urca, the Rio de Janeiro nightspot that was the site of their earliest stage triumphs. Expecting to be greeted as they had been in the States, that is, with wide-open warmth and fully appreciative affection, they could not have been more confounded by the chilly atmosphere that waited for them inside.

There have been many theories put forth for Carmen’s overly cool reception at the Urca: from the unusually stuffy society crowd present, which included the wife of conservative strongman, President Getúlio Vargas (rumored to be one of the singer’s former lovers but long since disproved by writer-journalist Ruy Castro); to the range of material chosen for the affair, an innocuous combination of sambas and Carnival march favorites peppered with Tin Pan Alley pop tunes.

A perfect example of the type of song that drew such ire from audiences in Brazil can be sampled in a revealing sequence from 1944’s Greenwich Village. In it, the star comes on to deliver a minor Leo Robin-Nacio Herb Brown number, “Give Me a Band and a Bandana.” Abruptly shifting gears, Carmen slips into an ebullient rendition (complete with exaggeratedly rolled r’s) of Dorival Caymmi’s “O que é que a baiana tem?” along with a slower tune, “Quando eu penso na Bahia” (“When I Think of Bahia”) by songwriter Ary Barroso. A minute later, she reverts back to bands and bandanas.

From that same motion picture, we have Carmen’s sizzling opening number, “I’m Just Wild About Harry,” by the team of Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, with additional interpolations (mostly, nonsense phrases in lightning-fast Portuguese) courtesy of Aloysio de Oliveira:

Oh, I’m just wild about

Samba, batucada, Carnaval e café

Por macumba, viramundo e uma figa de Guiné

And Harry’s wild about

Eu quero uma baiana com sandália no pé

E mandar um vatapá com um pouco de acarajé

The heavenly blisses

Of his kisses

They fill me with ecsta-

Se gosta de baiana é pra mim de colher

He’s sweet like peppermint candy

And just like honey from the

Bebi a cachaça a granel

Por mim ele apanhava papel

I’m just wild about Harry

Pois ele é um ioiô que gosta dessa iaiá

E é louquinho por uma samba lá na praça Mauá

He’s just wild

Anda louquinho por mim

He’s nuts!

Sujeito louco como ele eu nunca vi

About me!

(Copyright © 1921 by M. Whitmark & Sons /

Portuguese lyrics by Aloysio de Oliveira)

The sudden transition from Carmen’s heavily accented American English to free-flowing Brazilian Portuguese — and back again — is still quite jarring, even to modern-day ears. One can only imagine the shock it must have engendered in Brazilian audiences upon their hearing this contextual mishmash. In all probability, she most likely gave the folks at the Urca a fair and reasonable representation of the kinds of tunes that had bowled over hard-to-please New Yorkers.

There were other motives for her poor showing, one of them being a persistent and troublesome cold that dogged her every time she traveled by boat. Another was the casino’s use of an unfamiliar orchestra behind her onstage, instead of her usual six-man lineup. In any event, these paltry explanations fail to provide a truly satisfying glimpse into the ambivalent feelings conveyed by that Rio nightclub audience toward the baffled diva.

Ostensibly, a common enough fate had befallen Carmen that had also been shared by Bidu Sayão, (Antônio) Carlos Gomes, and several other of their fellow citizens, particularly when confronted with their own notable achievements away from Brazilian soil: that of a tangible and totally unwarranted resentment for having made it big abroad without their country’s approval or consent — as if these were absolutely necessary to affirm one’s position at home, or anywhere else, for that matter.

As anthropologist Roberto da Matta once observed about former soccer player Pelé, “To be successful outside of Brazil is considered a personal offense to Brazilians.” This simple yet insightful analysis was never more accurate than when applied to the seesawing musical endeavors of Carmen Miranda. After that critically panned appearance, the dejected singer and her band withdrew for a two-month rest, a period principally taken up by the group to revamp its basic song structure into something that more closely resembled an overt form of social commentary.

With that in mind, Carmen emerged from her isolation brandishing a buoyant new number, “Disseram que voltei americanizada” (“They say that I came back Americanized”) by songwriters Vicente Paiva and Luiz Peixoto, in the faces of previously unresponsive patrons. A cracklingly lyrical defense of her supposed conversion to American ways — and mockery of some distinctly Brazilian ones — this cleverly written topical ditty was a huge hit in Rio. It accomplished the desired effect of re-catapulting the star to the top of her seaside area stomping-ground:

They say that I came back Americanized

Loaded down with money

That I am filthy rich

That I can no longer stand the sound of the pandeiro

And that I bristle when I hear the cuíca

And they say that I’m always busy with my hands

And there’s a rumor going around

That I have no more spice, no more rhythm, no more anything,

And all the bangles that I used to wear don’t exist anymore, not one

But why are you throwing all this bitterness at me?

How could I come back Americanized?

I was born with the samba and live where it is played

Where it is sung all night long, that old samba beat.

In the street where the hustlers are, they are my favorites,

I still say ‘eu te amo,’ and never ‘I love you.’

As long as there is Brazil, whenever it is mealtime,

I still order shrimp soup laced with cucumbers.

(English translation by the Author)

But the damage to her unshakeable self-esteem had been done. Had she really turned her back on her own people? Had she abandoned the poor favelados (“slum dwellers”) she had so sympathetically sung about, for the easy money and get-rich-quick schemes of greedy North American capitalists? Had she also sold off her highly prized charms so cheaply to New York audiences for a fleeting grasp at personal gain, as they all claimed she had? None of these charges were true, of course, but the negative aspersions that continued to be cast at Carmen while she was holed up in Rio would only serve to strengthen her iron-willed resolve to pin her future career hopes on wartime America.

Disappointingly, the remainder of her Hollywood-film output would consist of a mixed-bag of garish Technicolor® spectacles (That Night in Rio, 1941; Week-End in Havana, 1941; Springtime in the Rockies, 1942; Greenwich Village, 1944), ridiculous tutti-frutti headgear (The Gang’s All Here, 1943), and uninspired comedic romps (Four Jills in a Jeep, 1944; Something for the Boys, 1944; Doll Face and If I’m Lucky, 1946; followed by Copacabana with comedian Groucho Marx, 1947; A Date With Judy and Nancy Goes to Rio, 1948), culminating in an ignoble guest effort in the 1953 Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis haunted-house spoof Scared Stiff. While they proved financially lucrative at the box office, these projects were eminently unworthy of her talents, which extended past her familiar, hip-swinging milieu to fashioning and designing her own elaborate wardrobe, footwear, and headgear.

In spite of the risk to her carefully constructed image, the mid-career tradeoff of her Latin-based musical livelihood for the uncertainty of Los Angeles’ fickle film community was a chance that Carmen Miranda was only-too-willing to take, and never given enough credit for having done so. In giving up her uniquely Brazilian identity for an all-purpose, stereotypical compilation of ersatz Latinate femininity, she acquired a definitive degree of international recognition, along with a hefty amount of notoriety, as that infamous snapshot of Carmen without her underpants would plainly show. Moreover, the drastic modulation of her inbred Brazilianness, mingled with the bland indifference her compatriots had detachedly shown her at Cassino da Urca, deeply affected Carmen’s inner psyche and helped to erode what little pride she had left in her American accomplishments.

These, in turn, would serve as the absorbing subject matter of numerous posthumous books, articles, and publications — in addition to a revelatory cinematic study, Carmen Miranda: Bananas Is My Business (1994), by Brazilian filmmaker Helena Solberg about the entertainer’s later life struggles with fame. Highlighted by a whirlwind 1947 marriage to minor American movie producer David Sebastian (whom she met on the set of Copacabana); a longtime dependence on uppers and downers; an abortion and miscarriage; alcohol abuse (a carryover from husband David); depression, hypochondria, electroshock therapy, and more, Carmen’s mounting personal misfortunes would combine to bring about her complete mental and physical breakdown sometime in December of 1954. The prescribed method of treatment involved a four-month period of rest and recuperation in Brazil — her first trip there in fourteen years, spent reacquainting herself with relatives and old friends, and slipping in and out of seclusion at the Copacabana Palace Hotel in Rio de Janeiro.

She returned the following April to the U.S. to quickly resume her busy nightclub and television schedule — too quickly, some would say (thanks to David Sebastian and his persistent transcontinental telephone calls), leading to a silent heart attack as she finished taping a strenuous dance sequence for The Jimmy Durante Show on August 4, 1955.†

Later on, at her Beverly Hills mansion and in the early morning hours of August 5, her lifeless body was found by husband David and her mother, Dona Maria. Carmen had expired prematurely at forty-six, the victim of cardiac arrest due to occlusion of the coronary arteries.

Carmen Miranda’s shocking end and tumultuous Rio de Janeiro funeral produced a staggering outpouring of grief in the country — a vivid example of pent-up guilt feelings for the way the Brazilian nation had treated the dearly departed movie icon when she was alive. Accompanied by David Sebastian and her mother, Carmen’s body was flown to Rio for burial in the famed Cemitério de São João Batista (Cemetery of St. John the Baptist) in the neighborhood of Botafogo (2), in accordance with the star’s wishes.

It also struck a foreboding chord with Bidu Sayão, Brazil’s other international musical exponent, and a fervent friend and follower of the once energetic entertainer. Only a month before Bidu had suffered the loss of her first husband, the late impresario Walter Mocchi, recently interred in a Rio cemetery. And, in a manner of speaking, she had witnessed the slow and steady passing of her own Met Opera career, what with her having to contend with a regime change at the company she had so long been associated with.

The new administration, put in place in October 1950, was headed by crusty general manager Rudolf Bing. Bing was peculiarly unreceptive to the popular Brazilian singer’s request to perform in Pelléas et Mélisande, one of her Gallic specialties. In his book The Last Prima Donnas, Italian author, critic, and publicist Lanfranco Rasponi termed Bidu’s performance in the work as revelatory: “[S]he was perfectly cast [as Mélisande], for she conveyed the evanescent mystery of this lost creature with a voice that was like gossamer.” Mr. Bing it seemed had an aversion to the standard French repertoire (he also had another singer in mind for the part). But his firm support of Verdi and Puccini, and outright backing of the Mozart canon, gave Bidu renewed hope that she would be given a fair stab at some of the meatier items on the Met’s operatic dinner-plate of works.

Such was not to be. She sang in only four performances of La Bohème, the last of which, dated February 26, 1952, was her good-bye to the old house. It was followed two months later by a final April 23rd appearance on tour, in Boston, as Manon, the role of her Met debut.

“I am proud,” she would later remark, “and I did not want to wait until I was asked to leave.” It was commented on at the time that Bidu Sayão had left the Metropolitan at the top of her form, and with few regrets. “At the end of my career I appeared in San Francisco as Margherita in Mefistofele and as Nedda [in Pagliacci], but by then I was willing to take risks, for I was about to put an end to my activities.”

Cutting back on her operatic appearances, she limited all future engagements to the concert hall, but wallowed joyfully in her newly acquired freedom away from the lyric stage. In the same year as Carmen Miranda’s wedding in Beverly Hills, Bidu and her husband, Giuseppe Danise, purchased a home in Lincolnville, off the coast of Maine and reminiscent of her family’s littoral abode in Botafogo. They called it Casa Bidu. After her retirement from the Met, she and Danise would spend considerable time there together, interspersed with occasional side visits to New York City and the Ansonia Hotel, where the couple stayed when they were in town.

But more shattering news would arrive in January 1957: Arturo Toscanini — mentor, admirer, adviser, and steadfast supporter — died at his home in Riverdale, New York, at the ripe old age of eighty-nine. This was too much for the sensitive soprano to bear, as she now resolved to terminate her singing career before the year was out.

“That decision,” Bidu admitted to reporter Maria Helena Dutra, in that December 1973 interview for Veja magazine, “came about as well because my ninety-year-old mother had been extremely ill. And my husband complained constantly of being left alone because I was leading a gypsy lifestyle. I felt then that my family needed to come first.”

In 1958, Bidu bid a fond farewell to concertizing, in the same historic location (Carnegie Hall), singing the same lyrical showpiece (Debussy’s La Damoiselle Élue), and with the same orchestral forces (the New York Philharmonic) as those of two decades prior, when she was first introduced to North American audiences by the incomparable Italian-born Toscanini; except that on this occasion, the program in question was in the capable hands of a noteworthy Belgian, the conductor André Cluytens. He would solemnly assist Bidu in drawing a final curtain on the predominantly classical cycle she had begun for herself back in the spring of 1936.

“It’s hard to quit,” she told The New York Times, “one feels so empty. But how much better to do it when the public remembers you well. Rosa Ponselle did it. Bori did it. Not many do. Now I could smoke, stay up late at parties, and catch a cold.” Reminiscing about those years to Veja, Bidu admitted that, for a while, she lived with her “past glories, surrounded by journalists.” When she finally called it quits, “all of a sudden there was this tremendous void” in her life, but the choice was made, and she em-braced it with open arms.

Within a few years of that defining concert, second husband Giuseppe Danise would join the celestial ranks of the other prominent figures in Bidu’s life: uncle Alberto Costa, soprano Elena Theodorini, tenor Jean de Reszke, Madame Emma Carelli, impresario Walter Mocchi, maestro Arturo Toscanini, and composer Heitor Villa-Lobos, a lifelong collaborator and close personal acquaintance. All had made incalculable contributions to her profession and art. While each had received their just rewards, Bidu would continue to be feted, honored, and fawned over, for years to come, by ardent aficionados both here and in her native land.

With all that she had seen and done in her field of choice, what was there left to say about Brazil’s most exalted opera personality? Taking note of her award-winning 1945 Columbia Records rendition of Villa-Lobos’ Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5; and her elevated status as a major interpreter of that composer’s works, along with those of the less familiar-sounding Hernani Braga, Henri Duparc, Gabriel Fauré, Reynaldo Hahn, and Francisco Mignone, Bidu’s stage and recorded milestones went far beyond the norm for a native-born classical performer of her time.

In fact, there was no denying, or even downplaying, her importance as a pivotal player in the development and spread of opera in-and-around the Brazilian landscape. Although some critics would go so far as to admit that her (and Carmen Miranda’s) peak period of activity spanned the length of U.S. involvement in the Second World War — with its emphasis on the Good Neighbor Policy and the resultant rationing of the gene pool of foreign artists (and with Bidu having failed to appear in her native land between the years 1937 and 1952) — they were not supported by the evidence.

“I get offended when people tell me that I’m not patriotic,” she told Veja magazine. “I’ve always represented my country with much dignity.” But what was it that made the little diva so endearing to opera buffs? What carefully guarded secret had she possessed that so inspired the loyalty and admiration of even the most hardened of music critics?

On the whole, it can be added that in almost every respect the lovely lyric singer exuded that rare and indecipherable star quality known as charisma. Added to her matchless stage deportment, it manifested itself in the purity and ease with which she projected her small but penetrating instrument; marvelously self-contained within a miniature yet finely sculpted frame; and perfectly suited for the nobility and majesty of only the most theatrical of dramatic contrivances — chiefly, the opera.

With her usual, self-effacing modesty, soprano Bidu Sayão saliently and quite succinctly summed up her own precious vocal artistry in a 1989 broadcast interview for New York radio station WQXR-FM:

"I had something appealing, I don’t know what. The sincerity of my singing. I give my heart. I give my soul. I give myself."

She gave of herself one last time, when, in 1995, the Beija-Flor Samba School of Nilópolis invited the elderly but still determined petite grande dame of grand opera to appear in the annual Rio Carnival parade. Bidu’s life story had been transformed into the school’s theme for that year, and she was more than happy to oblige as it provided the bona fide Brazilian charmer with a pretext for visiting Cidade Maravilhosa (Marvelous City*) once again.

Her attire was that of a typical Northeastern baiana, the only conceivable dress she could have worn under the circumstances — and a most fitting tribute to the memory of Carmen Miranda in her prime. With that simple gesture, two hitherto incompatible entertainment forms had, for one brief instant, successfully melded into a singularly grandiose public display. For what is Carnival and opera, anyway, if not outsized representations of all that we would like for reality to be?

Characteristically, the nonagenarian Bidu stole the show.

On March 12, 1999, after a brief illness, soprano Bidu Sayão permanently left the world spotlight. She died at Penobscot Bay Medical Center in Rockport, Maine, two months short of her ninety-fifth birthday.

Her death brought to a quiet close a most remarkable chapter in Brazilian music history, one that Bidu had so conspicuously made her own. “[D]uring her career days, she held audiences in the palm of her hand,” remembered Schuyler Chapin, ex-Commissioner for Cultural Affairs in New York and a former general manager of the Metropolitan Opera Company. “Whether on the opera stage, the concert hall, a living room, or just in conversation…she was, hands down, one of the public’s favorites.” But the length of an individual’s physical life does not necessarily translate into longevity in the public’s mind, especially where it concerned the new and unconventional in music.

Alas, few of the current generation of Brazil’s knowledgeable music lovers have even heard of Bidu Sayão, much less been made aware of her past accomplishments. Yet, ever more enthusiastic disciples of Música Popular Brasileira have become enthralled all over again by the flashing eyes, the free-flowing arm movements, and the fluttering vocal lines of that too-short-lived curio named Carmen Miranda. A major re-appraisal of her work appears imminent and overdue and is sure to follow in the wake of this modern re-evaluation.

In the brief time she spent with us, Carmen’s musical and entertainment legacy had apparently won out over — or even surpassed — soprano Bidu’s now overlooked ones. Indeed, the entertainer’s tragic, un-foreseen death and subsequent re-acceptance into contemporary Brazilian cultural society can be read, should we choose to, as the final triumphant victory over her earlier career adversity. ☼

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

CREATIVE CONSULTANT, WRITER, COLLABORATOR, TEACHER, LECTURER, PLAYWRIGHT, and translator JOSMAR LOPES has over fifty-plus years of exposure to — and love for — the opera, movies, musical theater, soccer, popular music, classic drama, and the performing and fine arts. Although his professional career has been focused primarily on the financial services, medical devices, and retail services industries, his heart has always been with the arts.

A native of São Paulo, Brazil, Josmar immigrated to New York in 1959 at an early age. Growing up in the Bronx and Manhattan, he was privy to a wide range of artistic and cultural activities. Josmar received his Bachelor of Arts degree in History from Fordham University, with a concentration in Art History, Theology, Philosophy, and European and Medieval History. He earned a Certificate in Management Practices from New York University, and Diplomas in Paralegal Education (also from New York University) and Teaching English as a Second Language (TESL) from the New School for Social Research

More recently, Josmar has developed a number of cultural-exchange projects, including a musical-dramatic play about Carmen Miranda entitled Bye-Bye, My Samba (Adeus, batucada); Mio Caro Giacomo (My Dear Giacomo), a seriocomic look at Italian opera composer Giacomo Puccini and the problems he faced in writing and staging the opera Madama Butterfly; and Bronx Boy (currently in development), a fictional account of a Puerto Rican family growing up in the South Bronx.

In the midst of this blizzard of activity, Josmar still finds time to dabble in his favorite subjects, i.e., watching and analyzing movies, contributing articles to his blog Curtain Going Up! (Reviews by Josmar Lopes) and listening to the Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts.