LIFE & ITS VERSATILITIES

Life

Life is an unchosen gift which we should try to make the most of. In our ignorance, we generally waste most of our time. By the time we realize its importance, much of it has been wasted. It is a pity we do not carry forward knowledge from our previous incarnations and we have to start afresh. Life remains a process of learning only. Life can be best spent if we understand in the beginning that we are not the masters of the game. We are passive participants. We have been dealt some cards and we are expected to play the game to the best of our wits.

The important thing is that we should play a fair game. Those who underplay or overplay it, soon come to grief after a brief period of exuberance. We can instill meaning into our lives by being good at heart, being helpful to others, and not harboring ill will against anyone. It is good if we can forgive the people who have played false with us. The most important thing in our life is not wealth, nor possessions, but peace of mind and happiness. And we should not disturb others’ happiness, nor let others destroy ours.

Death

We erroneously think that death comes at the end of life. And it is a nightmarish experience. Yes, death is a bridge between life and eternity. Nobody has looked beyond what lies at the other side of the bridge. Death is a lingering phenomenon, which shadows our life. Every moment that we live, actually dies. So, all the day, the process of dying is on. Moments which we have lived are dead now, and they are becoming past. It should be remembered that there is no life without death, and no death without life. Inanimate things do not die. For a living thing, it is a privilege to decline as time passes, and finally die, giving space to the new. It is better we learn to understand that where there is life, there is death.

Birth

Birth, marriage and death are three occasions in life which are considered most important. When we come to life, we have no options. We do not know who places the order for us, and who delivers us on to the earth. Mother is there, but she too is a passive agency. The decision for a person to be born in a particular family is taken at the highest level. The person is not consulted where he will be born, when he will be born, and what will be his colour, his religion, and his stature. Things are just given to him like gifts in one stroke and he is made to move. Now, it is in our hands how to understand this life. The entire life sometimes passes and still we are unaware of our destiny. Why a man has come to this earth? This question we must ask ourselves. We have not come simply to earn money and eat and drink and make merry. There are other reasons, some higher reasons, which bring us to this earth. In the absence of that knowledge, for most of he people, it is a blind trudge only.

Marriage/Family

A man has to raise a family for the purposes of reproduction, and our society wants him to marry. Everybody marries, everybody has one or two kids, and people know the kids have to be given education, and when they grow up, married off. But the task is very tough. The most basic issue for the couple is to stay together even if they do not understand each other. Kids too when grow up, no one knows what they will be in their lives, even if they are given equal nourishment.

The essential issue here is: Should every one marry? Those who cannot compromise with others, must not marry. If you marry, then be ready to share your time with someone whom you don’t know. It is better people who marry know each other for at least six months. Once kids are there, no couple should be allowed to separate so long as the kids are below the age of 5 years. It is easy to break a family, and it is very difficult to stay together. It is better if we try to stay in marriage. Breakage can destroy the lives of the kids. Family is the smallest unit of the society. It must have harmony. We should see there is compatibility between the partners. And there is love too. Otherwise, it is a picnic party which ends in brick bats.

Children

People these days are so fed up with their lives, and careerism, that they do not want kids. But in view of the modern wisdom, they go for women who are in service. They have to postpone childing under pressures of the work. Then, they do not have quality time for their infant kids. We are not fair. Because, this is what the kids will visit upon us when they grow up, and we grow down.

It is essential we allow the kids to grow, and acquire the qualifications they wish to get, join the stream of life which best suits them, and then, separate them from the main family unit, and let them run their own family. Distance is a great healer. It is a must if we want to see peace between the MIL and the DIL. [Mother-in-law and the Daugher-in-Law].

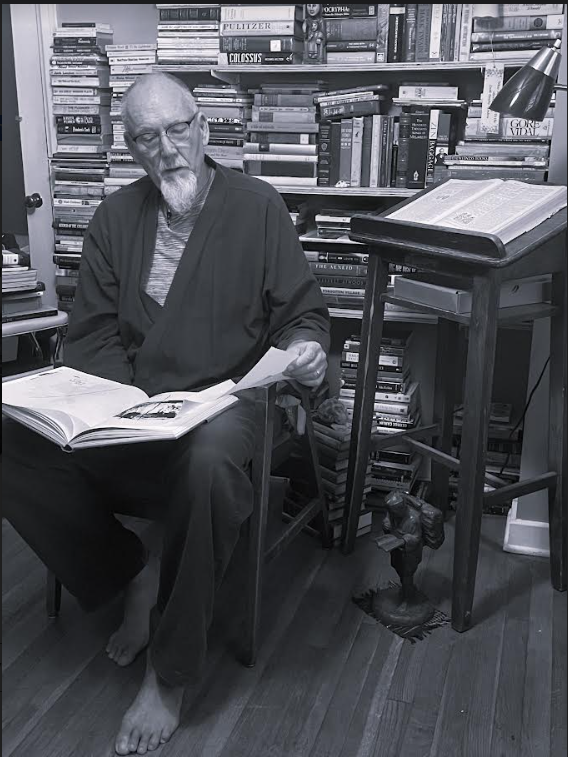

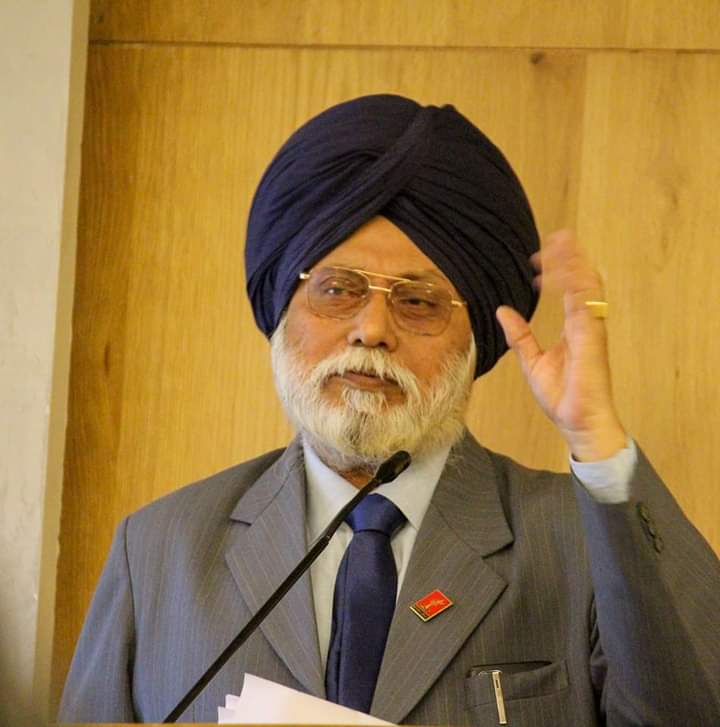

Author:

Dr Jernail Singh Anand, President of the International Academy of Ethics, is author of 167 books in English poetry, fiction, non-fiction, philosophy and spirituality. He was awarded Charter of Morava, the great Award by Serbian Writers Association, Belgrade and his name was engraved on the Poets’ Rock in Serbia. The Academy of Arts and philosophical Sciences of Bari [Italy] honoured him with the award of an Honourable Academic. Recently, he was awarded Doctor of Philosophy [Honoris Causa] by the University of Engg and Management, Jaipur. Recently, he organized an International Conference on Contemporary Ethics at Chandigarh. His most phenomenal book is Lustus: The Prince of Darkness [first epic of the Mahkaal Trilogy]. [Email: anandjs55@yahoo.com Mobile: 919876652401[Whatsapp] [ethicsacademy.co.in]

Link Bibliography:

https://sites.google.com/view/bibliography-dr-jernal-singh/home