My Doppelganger

In early March of 2020, my sister, Debi, and I took a yellow cab on our lunch break to the Volta Art Fair, near the West Side Highway. She had just purchased a small painting from an artist who had a booth there. I loved the painting and was looking forward to seeing more of the artist’s work. On the day we went, we heard she would be present.

“Let’s talk about shaking hands,” I said.

“Why, are you afraid of Corona?” Debi said.

“I don’t know. It’s just not a good idea.”

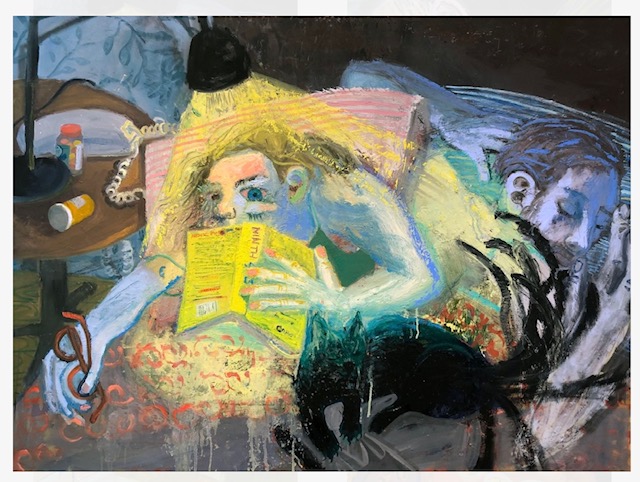

We went upstairs, chitchatting with every step, and then I saw it. It was large, horizontal, and colorful. I couldn’t turn away. There was a couple in bed. The husband was sleeping in a purple haze on the right side; you had to look hard to realize he was even there. At his feet was a black cat with a swishing tale that at first I mistook for a giant spider. The woman was harshly lit by a reading lamp directly over her blonde head. She had a yellow book in one hand and reading glasses in the other, and she looked frazzled and anxious. A bottle of prescription pills lay on its side on her bedside table. She had one blue eye that overshadowed the other in sheer size. It shimmered, staring at the viewer. She was like an ogre but relatable.

“Les, that is so you,” Debi said. I understood what she meant.

The artist appeared. Debi shook her hand. I didn’t. I asked her what book the woman in the painting was reading.

“The Ninth Street Women,” she said.

“Oh!” I said. “Our great aunt was an artist in that circle,” and suddenly we had a lot to chat about.

At night, all I wanted was to read peacefully before closing my eyes and falling asleep. But it was a struggle: My husband, Val, kept asking me to turn off the light. I tried the Itty Bitty Book Light, but that was unpleasant. Instead, we bickered. “In a minute,” I’d say, or, “Let me finish this page” or “paragraph” or “sentence.” He would come back with, “It’s midnight,” or, “I have to get up early,” or the most offensive, “Why don’t you go read in the living room?”

I talked some more to the artist, and before I knew it, I was handing the gallerist my credit card. I had never made a purchase like that before. It was more than I was used to spending but within my means. The painting would be delivered to my home in New Rochelle. I couldn’t believe how happy I was.

A few days later, New Rochelle was in the news. A one-mile containment zone was going to be established because there was a Covid outbreak in my neighborhood. People in white hazmat suits were going to homes on my block where people were infected. The National Guard was there, although I wasn’t sure why.

The day before, I had taken the train to work. The platform was crowded. A man coughed, and I felt his hot breath on my neck. As I inched away from him, he said, “I’m not Chinese, you know.” I carried this unpleasant encounter into the city and then stayed only half a day. I said a tentative goodbye to my co-workers. I didn’t know if I would be allowed to leave the containment zone to come to work the next day. I considered fleetingly the shoes in a basket under my desk and whether I should bring my stuff home. But the thought of packing up overwhelmed me, and I left the shoes behind.

My older son, Aaron, was at Albany finishing his senior year of college. Oliver was commuting to Manhattanville not far from our home. Val, who traveled for his job, was suddenly grounded. That night we went to bed, but I couldn’t sleep. I turned on the TV once Val was safely snoring and purchased the movie Contagion. I watched it to the end, and at 2:30am I emailed my employer’s HR department. I asked if I should come to the office in the morning, considering where I lived, ground zero. I got an answer at 5:30am saying, “Not until further notice.”

The painting arrived on the first day of lockdown, like a new member of the family. I hung it over the fireplace; at four feet across and three feet high, it was significant. Val came out of his office and looked at me as if I had gone insane. “You bought a painting?” he asked, his voice shrill. I ignored him. Oliver emerged from his room, looked at it and said, “Wow!” Aaron arrived later and said, “Cool painting.” Since our first floor was an open plan, you could see it from the kitchen, dining area, and TV room.

I locked our front door and settled myself on the couch in view of my new best friend.

I had been a banker all my life and had held this last job for nearly 14 years. The bank I worked for had been acquired, and I was going to be let go with a severance package at the end of May. I was a bit unmoored by this loss and would never have left my employment willingly, but the termination date secretly excited me. I hated the grey walls of my office, the constant smiling, the feigning of interest in a field I didn’t really care about. For a few weeks after lockdown, I did not work at all. When I started up again, my workload was light.

I liked being home. My sons took their classes virtually, each of them in their rooms. I loved their proximity and that we were all together. I cooked, played with my puppy, went on long walks with her. I sometimes napped in the middle of the day. Words that seemed archaic, like quarantine, became common. I learned new words like Zoom. I took my yoga classes on it. I wore sweats daily. Makeup was optional.

I carved out a space in the living room that was just for me. I found an old desk that a neighbor was giving away on Facebook and had the boys put it to the right of my painting. I placed trinkets on it, a framed library index card, and some books. I sat there at my desk and daydreamed, and when I sat there, I was invisible and no one bothered me.

I started purchasing things on Amazon. I ordered the yellow book from the painting, which I didn’t realize was over 1,000 pages, and read it in full view of that blue eye, another woman in this house full of men. I read about Lee Krasner and how her fame was overshadowed by her husband’s.

I returned to my office one last time on my end date to sign my termination documents and collect the shoes from under my desk. There were only three people there; they stuck their heads out of their offices like moles. I was struck by their pallor. As I walked out of the building, a box with my things in my arms, the smile on my face was irrepressible, even if it was hidden by my home-made mask.

For the first time in my life, my crucial waking hours were mine to do with what I wanted. I read some more. The next chapter was about Elaine de Kooning. If only she had been born a man. I searched for my great aunt’s name and found her mentioned several times, but not because she was an artist or a friend. She was a neighbor. Her paintings hang on my walls. They used to hang at the Leo Castelli gallery. I wondered how she became a footnote.

I pulled out a needlepoint canvas that I had started years before and finished it seated near my painting.

The boys bought a firepit for the backyard. The TV room turned into a gym with weights and a bench. Val bought a Peloton, which was slightly less expensive than my painting.

We watched a lot of TV. George Floyd died on my screen again and again as I tried to look away. Marches in the streets followed. A few months later, the capital was nearly overrun, and the word “sedition” left my mouth for the first time. I had to explain to Aaron and Oliver what it meant. We introduced them to The Sopranos, and Val and I reminisced about watching it together as newlyweds when I worked for a French bank. All the while, the woman from the painting and I glanced at each other from across the room.

Sometimes before bed, Val and I would discuss what we would do if one of us woke up sick. And then, before we turned off the light, I’d say, “Good luck to you,” and he’d say, “And to you.”

One day the gallerist emailed me asking if a museum could borrow my painting when the pandemic was over. When I told Val, he was suddenly proud of our acquisition over the fireplace.

“Will it gain in value?” he asked.

“Probably,” I shrugged.

“Will it say ‘On Loan from Leslie and Val,’” he asked.

“No,” I said. “It will only have my name on it.”

This made both of us laugh. He snapped some pictures with his phone as if he were in a museum. “What a great painting!” he said, admiring my purchase.

“Step aside,” I said. “You are too close.”

Leslie Lisbona has been published in various literary journals such as Synchronized Chaos and most recently in Wrong Turn Lit, The Bluebird Word, and Dorothy Parker’s Ashes. She has recently been featured in the New York Times Style Section. All her published essays can be found on Substack.