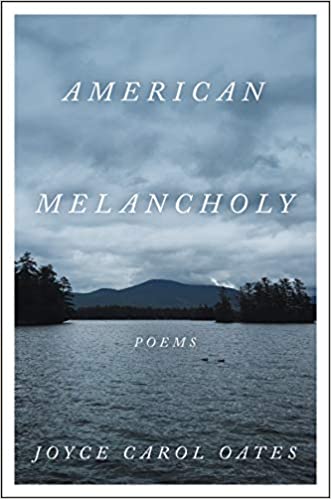

Human is as Human Does: A Review of American Melancholy by Joyce Carol Oates

Reading American Melancholy (Ecco, 2021), the new collection of poems by Joyce Carol Oates, I thought: America is manic in our uncritical self-esteem and self-confidence, Joyce Carol Oates is mantic in her suggestion of where we are going and poetic descriptions of where we have been — [I couldn’t resist]. She begins the collection with a husband reading the Nation in the ease of a hammock. A poem in which doubt is delivered lightly, easy to bear in the beauty of the metaphors:

before dusk rises from the earthbefore the not-knowing if (ever) (again) the earthwill turn on its axis to the light, the great furnaceof the light….

A virtuoso writer, Oates could have spent her career as a poet soothing our anxiety and we would have bought those books. Take a poem like “On This Morning of Grief” from a previous collection (Tenderness), it will make you feel absolutely good, but Ms. Oates has always had an Ancient Mariner bent towards awful seriousness in her storytelling, and by poem number two of Melancholy we are already heading there (there is the blithe, Apollinaire-like surprise of “Kite” — a shape poem with a soft pensive turn, like a kite — and her consideration of her cat Cherie’s purrrsonality traits [I couldn’t resist], Jubilate: An Homage in Catterel Verse, but “easy listening” poems are as rare here as in any JCO collection).

Poem number two, Exsanguination, a short lyric, its question like an uncryptic koan, makes me think of the age-old question, “What is the nature of suffering and what is its ultimate cause,” and if we listen to the poems in American Melancholy Joyce Carol Oates will tell us, and it is us.

The third poem, “Little Albert: 1920,” begins a consideration, in several poems, of American behavioral psychology experiments in the first half of the twentieth century. Again, a virtuoso writer, few can personalize, make us internalize, the physical and psychological vicissitudes of pain and fear as well as Joyce Carol Oates. At the end of “Little Albert,” the poem’s speaker — Little Albert himself — morphs into a sort of collective narrative speaker — we become Little Albert — the speaker is us:

All this was long ago. Things are different now. John Watson would not be allowed to terrorize Little Albert in his famous experiment now. Ours is an ethical age.

Or was it all a bad dream? Were you deceived? You were Little Albert? You were conditioned to fear and hate? You were conditioned to thrust from you what you were meant to love? You were the victim? You were the experimental subject? You were Little Albert, who died young?

The question this and many poems in the collection suggest to me is “are humans brutes, always at risk of engendering or falling into depravity?” With this question hovering over many of the poems, the poem which stands out the most in American Melancholy is “To Marlon Brando in Hell,” where the answer is “yes,” even for this seemingly larger than life talent. The speaker here is a woman the exact age of Joyce Carol Oates. The anaphoric repetition of the word “Because” gives the poem’s indictment of Brando, the man of such talent and promise, a sort of fever pitch. It begins:

Because you suffocated your beauty in fat. Because you made of our adoration, mockery. Because you were the predator male, without remorse.

Because you were the greatest of our actors, and you threw away greatness like trash…

Because the slow suicide of self-disgust is horrible to us, and fascinating as the collapse of tragedy into farce is fascinating and the monstrousness of festered beauty….

The speaker is angry and affronted that as a girl of fifteen she was “lured out” to take a bus to a neighboring city, “in the most reckless act of her young life,” to see Brando star in The Wild One in a seedy theater: “a place that would have been/ forbidden, if the girl’s parents had known./ What might have happened! — by chance, did not happen.” (Calling to mind what happened to the Grimes sisters in 1950s Chicago after venturing out at ages 12 and 15 to see Elvis in Love Me Tender: their naked bodies found by a road outside Chicago a month later — and evoking America’s true crime underbelly which much of Ms. Oates’ oeuvre has a Venn overlap into.) The poem covers many of Brando’s film successes and turns them all into indictment against what he will become as he manifests more and more moral agnosticism, perverts his success and his physical beauty into insane mockeries. Brando’s twisting of himself has twisted the speaker (only more reason for her anger), who after such sustained dismay and loathing still desires him: “Because you have left us. And we are lonely./ And would join you in Hell, if you would have us.”

If “To Marlon Brando in Hell” is maybe a centerpiece of the collection, as centerpiece I think of it more as panopticon, a central, substantial, and substantially damaged life that looks out at lesser known and unknown lives with greater or lesser degrees of damage, varying degrees of self-doubt, anguish. In “Edward Hopper’s ‘Eleven A.M.,’ 1926” the speaker is Hopper’s famous nude looking out a window (not as so famous as Brando, but famous). In the poem her self-worth is tied to the married man she waits for, leaving her in the loneliness and isolation of his too infrequent visits. Fans of Oates will want to bring her short story “The Woman in the Window” (which also interprets Hopper’s painting) into their consideration of the poem, but the more sinister elements in the story (contemplations of murdering the other by both) are not in this poem about unhappiness and frustrated fulfillment.

In “Old America Has Come Home to Die,” an “iconic” twentieth century vagabond, entirely one of Robert Service’s “men who don’t fit in,” returns home physically broken and vaguely remembered, his only value now to play himself and be videoed for a budding Ken Burns great-niece to make an “A” in her college Film Studies: “Tragic, vividly rendered & iconic.” In these cases, the speakers’ lives are perhaps atypical yet without pathology. There but for the grace of God could go us, but there are other speakers in Melancholy we will see as “other.” Like the damaged speaker of “Doctor Help Me,” obviously coerced as a minor into sex by her best friend’s father, her life now a disaster of promiscuous sex, that baby and more babies. But, she has the traumatic time-confusion of Porter’s “Granny Weatherall,” so how many babies? Hard to tell. This too damaged woman could not be us — and for Oates’ fans her anguished pleading for an abortion will call to mind Luther Dunphy from A Book of American Martyrs who could never be us.

Likewise, the Chinese doctor in the poem “Harvesting Skin” whose medical work forces him to become a sort of occasional serial killer could never be us. He is one of just a couple non-American speakers in American Melancholy, but is he truly un-American? — a question central to this collection of poems. America, us, the US, is a humane country. Many of us contribute to charities annually. Some of us even work in soup kitchens. “All” of us, respectable people, try to do good deeds. We are a humane country — littered by mass shootings.

Until we embrace, know the “other” as us, its pathology will continue to run through us unabated. To be truly human, be really better Americans, we have to know the part of us that is sick, and we have to want to be cured. Otherwise — on page 40 of American Melancholy is “Apocalypso.” For me its “too late warning” is buried in the poems like a key. I invite readers to read it and the other poems in American Melancholy, the latest book by the reigning Queen of American literature.

A US Army combat veteran, Steven Croft lives happily on a barrier island off the coast of Georgia on a property lush with vegetation and home to various species of birds and animals. His poems have appeared in Liquid Imagination, The Five-Two, Ariel Chart, Eunoia Review, Anti Heroin Chic, Synchronized Chaos, and other places, and have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net.