Prehistoric Enchantment of Twentieth Century: Popularizing Fairy Tales of Science: Dragons of Romance and Dinosaur Renaissance

Examine a close reading of Jurassic Park with textual references and critical perspectives.

“The Lost World: Jurassic Park” franchise by Michael Crichton is a novelization of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein Or The Modern Prometheus”. Michael Crichton’s masterpiece of the science fiction genre satirically critiques scientific and tech revolution, biological evolution, DNA research, paleontology and chaos theory. Modern filmic adaptation stages the mise en-scene and psychodrama of Jurassic Park: Fallen Kingdom and Jurassic World Dominion through animatronics and computer generated imagery. Isla Nublar conservatory is a themed park of cloned dinosaurs genetically engineered and genetically modified from the fossilized DNA by International Genetic Technologies Inc.

InGen. Mathematician Dr. Ian Malcolm and geneticist Dr. Henry Wu perform pharmaceutical experimentation upon these captured herds of dinosaurs in the setting of Isla Nublar in Jurassic Park: popular science fiction and lost world culture of the paleontological deep times. Extremely rare species are preserved in conservatory but nonetheless,these predators become a threat to visitors. We must embrace complexity theory and /or chaos theory to examine the aftershocks and aftermath of climate change exposing environmental managers of Yellowstone National Park. Medical doctor buttressing as a bestselling novelist to publicize paleontological paranormalism and spiritualism of evolution, dinosaurs and extinction to truly massive audiences. Satirical critiquing of hubris and corruption of industry and politics intricately foreshadows behind the scenes of verfremdungseffekt.

Western world industrialization, rationalization and global colonialism within the twentieth century have been sequestered of wonder and mystery, thus leaving a legacy of skeptical disenchantment. Language of myth, magic, romance, folklores and fairy tales are encapsulated in the engendering of dreams, visions and dantesque journeys, speculative illustrations through palentological-geological novels like “Jurassic Park” and “Lost World”. Even pure scientific discovery is an aggressive and penetrating act viscerally banishing equilibrium of flesh in the robotic cyborg posthuman. Protagonist paleontologist Dr. Alan Grant is gobsmacked with Ellie Sattler to discover prehistoric remains of atavistic beasts and meets John Hammond, the venture capitalist with growth potential in exchange for future profits founder of InGen and owner of Jurassic Park. Billionaire showman and pity bernam figure expostulates “That’s a terrible idea. A very poor use of new technology…helping mankind is a very risky business. Personally, I would never help mankind.”

John Hammond doesn’t feel humanitarian philanthropism and altruistic agency to cater for vaccination and immunization with bioengineering companies projects investments. His Visitor Center and Private Bungalow epitomizes eclecticism and eccentricities, while bereavement of fatalistic accidental death encounter epitomizes rationality of disaster from unemphatic corporate systems analyst. While strolling, the corporate magnate is flabbergasted by a tyrannosaurus roar (ironically defrauded of his own mischievous grandchildren’s recorder, he is fated to death trap by herd of Procompsognathus. Malcolm’s prognostication of awry of the genitalia female mutilation in the biological reserve.

Meanwhile computer scientist Dennis Nerdy unbeknownst to Malcolm smuggles dinosaurs embryos off the island and commits industrial espionage by infringing DNA samples to Biosyn because of his low salary and financial bankruptcy. Nerdy disables the park security system to pilfer the embryos initiating a cascade of failures disrupting electrical fences and what follows is a power outage stranding protagonists. Postpounding creepy sci-fi science outpacing morality, human beings fate, technocrats of nature or the nature’s apocalypse wrecking human survivalism exhorts human beings pantheism in exchange for fertility and bounty from mother nature Gaia.

With Wu’s assistance, John Hammond appropriates Jurassic Park to Modern Prometheus and Frankenstein, casting God to plague the world by unhindered and unregulated innovation is ripe for potential abuse and corruption; unless divination of celestial hierarchy intervenes the consequences of disastrous catastrophes imperils humankind. Icarus audacity of moira transgressing to critique insatiate profittering capitalism through central planning of greediness and recklessness embodied into economic rationalism associated with consumption and production. We should let nature take its course without coercion, curtailment, censureship and containment.

Soviet communists looking at death and despair all around them while Hammond is despotic and tyrannical to defend central planning policies and procedures to master nature. “You decide you will control nature”. “You are in deep trouble because you can’t do it. Here you have made systems which require you to do it. [..] ‘’there’s a sudden, radical and irrational change which is built into the very fabric of existence.” Hubristic and naive characters like Hammond, Hu and Arnold wish to enforce measures to protect endangered species and mitigate global warming contrasting pragmatists and realists Grant, Sattler and Malcolm.

Further Reading, References, Endnotes and Podcasts

Wikipedia readings

63.6M subscribers

3.19K subscribers

131K subscribers

UCL Press

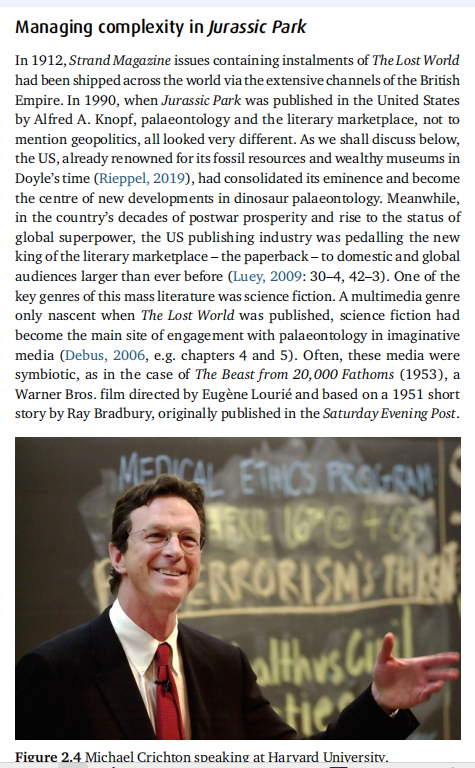

Chapter Title: Arthur Conan Doyle, Michael Crichton, and the case of palaeontological

Fiction, Chapter Author(s): Richard Fallon and David Hone, Book Title: Palaeontology in Public, Book Subtitle: Popular science, lost creatures and deep time, Book Editor(s): Chris Manias, Published by: UCL Press. (2025)

Cover of a Book

Can I buy you a drink?” the tall, rumpled man asked the petite woman in the tavern. She was a looker, he thought, lightly licking his lips.

She narrowed her green eyes at him, looked him up and down and replied, “I don’t know, can you?”

Ralph became newly conscious of his shabby street clothes. He was still attired in the garb he favored when working undercover for the police department. But, his thirst for a beer had been so great that he’d dropped in without going home and changing first.

He managed to respond, “When your students get it wrong, do you make them do it over again until they get it right?” He’d noticed the “Teacher of the Month” ribbon affixed to her top.

She couldn’t suppress a smile. “Do you always answer a question with a question? But, I guess I just did that too. Never mind, buy me a drink – it’s been a tough day. May I buy you a drink? From the way you are dressed, I imagine I can afford one better than you.” She was ribbing him, he thought.

Ralph called out “Garcon, we would like to order drinks. She’s buying me your cheap beer. What am I buying for you, dear?”

“I’ll have an atomic gin – I mean gin and tonic – sorry for my name for the drink. Drink enough and they are atomic – blow your mind.”

They engaged in getting-to-know-you small talk for some time, consuming several libations in the process. Ralph didn’t reveal his occupation; he saw no reason to tell “Annie” that he was a cop. It was partially defensive; a lot of citizens were turned off by his choice of careers. Besides, he was enjoying the charade of being mysterious. After all, it was part of his lifestyle.

Finally, Annie put the question to him: “What do you do for a living, Ralph?”

He smiled. “Ah, but that would be telling.”

“Can you at least tell me if you’re legally employed?” Annie asked, with a little pout.

“Very legally, if there is such a thing. I don’t like to talk about myself unless I’m being paid, which has never happened, but I would like to know more about you, Annie.”

“I educate business men.”

“Just men?”

“Mostly men, but quite a few women have liked my lessons.”

“What do you teach those men and women?”

“You might need some lower level introduction before you would understand…” Annie realized she might be talking down to Ralph and stopped talking.

In the midst of an awkward pause, into the tavern walked Ed, who, like Ralph, was a vice cop. He worked a different precinct, however.

“Hey, bro’,” said Ed in greeting, slapping Ralph on the back. Suddenly Ed caught sight of Annie and drew up short. “You’re a little out of your territory, aren’t you?” he asked archly. Annie looked daggers at the man.

“Hey,” Ralph spoke up. “Do you two know each other?” He pointed alternately at the pair. “Ed?” he prompted.

“A lifetime ago,” replied the other man. Turning to Annie, he remarked, “You’re looking good.” Annie said nothing. Getting the message, Ed said, “I’ll check you later,” and he drifted off.

“How do you know Ed, Annie?” asked Ralph curiously.

“It was a…business relationship.,” she said shortly.

Warning signs began going off like fireworks in Ralph’s brain. How would he ever live down being taken in by a hooker? He must be losing his touch, he thought, and shook his head.

Annie became aware of Ralph’s sudden coldness and said, “Excuse me; I have to visit the little girls’ room.” She hopped off the barstool and vanished in the direction of the restrooms.

Ralph, meanwhile, with his cop’s intuition for the dark side of human nature, walked across the bar to find his fellow detective, Ed. He found him talking to a stunning brunette. He excused himself to the woman and drew Ed away from her.

“Hey, man,” he said once he had the other man to himself, “what’s the deal with Annie?”

Ed, annoyed at breaking the rhythm of his seduction of the other woman, said, “what do you want to know?”

“Where do you know her from?”

“It was a business transaction,” replied Ed.

“Damn,” exclaimed Ralph. “You mean she’s a pro?” He was mortified. It was as bad as he’d thought.

Ed’s face showed his amusement. “Relax, Ralph,” he said. “Annie is a professional–businesswoman. She taught a seminar last fall. You remember when I was considering retiring from the force and starting my own business? Well, afterwards we dated and I’m afraid it didn’t end well. In all events, there were hurt feelings all round. Excuse me, a lady is waiting for me, and I’d hate to disappoint her.”

When Annie returned, Ralph felt bad about suspecting her of being a prostitute. It was clear she had put two and two together and read his thoughts. She was decidedly colder now. He felt like he had to come clean.

“I’m apologize, Annie” he said. “I jumped to the wrong conclusions and I am sorry.” He saw her features soften. “Can we start over?” he implored.

A small smile blossomed on Annie’s pretty face and she said, “Alright. Everyone deserves a second chance.”

Ralph sighed with relief. “Do you think you might have a drink with me next Saturday?” he asked.

“If I say yes, can you leave the vice cop at the door?” she asked. “I’d hate to be on the scene of a bust,” she said wryly.

“Promise,” said Ralph. “How about Doug’s place, in the central west end?”

“Ok, I’ll meet you there.” Annie felt relief at the now relaxed vibe.

Out of the blue, Ralph asked, “Are you worried that I drive a car that matches the way I dress?”

“Ok, let’s just drop all that, but you could dress for a possible second date. By the way, I don’t mind dating a cop.”

Touche! He thought with a grin.

At dusk

I undress my curtains

The sun smiles at my bed

As I kisses the rays of hope

The morning calls out my name

Awakening with golf dimples

Positive thoughts – river in my heart

Flowing like a peaceful flood

That is a mirror that reflects/shines future

I spread myself

spray my wings and fly

As a smile hugs me

Every single day I rise after the short death

A World with One Shortcoming

Winter… Everything was covered in white snow. The leaves of the trees had long since fallen in autumn. Now, their branches were adorned with snow. Birds that loved warmth had flown to other lands. Ra’no sister, as always, was busy with housework. Her husband was not at home. It had been 20 years since they started living together. However, they had no children. Every night, Ra’no sister would raise her hands in prayer, pleading Allah for a child. Her husband, unable to bear their childlessness, drank alcohol every day, drowning his sorrow in it. Finally, today was a joyous day. Ra’no sister’s prayers had been answered. Allah blessed them with a baby girl. Ra’no sister’s happiness was boundless. She was so delighted that she named her daughter Sevinch (Joy). She cherished her daughter dearly. Unfortunately, Asror bro was not pleased. He was disappointed because a daughter had been born instead of a son. But Ra’no sister paid no attention to his reaction.

Several years passed. The girl turned six. Now, she had become more aware of the world around her. Her mother pampered her a lot. Whenever the little girl played, her mother would drop everything and play with her like a child. If Sevinch laughed, her mother laughed with her; if she cried, Ra’no sister would cry even harder. Maybe because she became a mother later in life, she was extremely protective of her daughter and did not trust anyone with her. If her daughter felt even the slightest pain, the world would feel suffocating for Ra’no sister.

One day, they went to the market. The little girl stopped in front of the toys and started begging her mother: “Mommy, I really like this toy. Please buy it for me, please, please!”

Unfortunately, Ra’no sister did not have enough money left to buy the doll. That night, the girl went to sleep feeling disappointed. But her mother did not sleep. She took a scarf, which she usually wore on special occasions, and made a doll for her daughter. She crafted it so beautifully that anyone who saw it would be delighted. Finally, Sevinch reached school age. Her mother told her father about it. But Asror bro responded: “She will not go to school. Instead, she should help you with household chores. Will studying bring me the world?”

However, Ra’no sister did not want her daughter to remain illiterate like herself. She wanted her only source of happiness in this world to be just as good as everyone else. So, despite her husband’s wishes, she sent her daughter to school. Just as she had hoped, Sevinch became the top student in her class. But as she grew older, she started to hurt her mother’s heart more and more. She became irritated by her mother’s kindness and often snapped at her. One day, when her teacher invited Ra’no sister to a parent-teacher meeting, her beloved daughter coldly said: “I am ashamed of you and the clothes you wear. Don’t come to the meeting!” Then she slammed the door and left. That day, Ra’no sister cried a lot. True, she had money, but she saved every bit of it for her daughter and never spent a single penny on herself. Yet, when Sevinch returned home, Ra’no sister hid her sadness and welcomed her with a warm smile, just like always.

Asror bro, however, still hadn’t quit drinking. That night, he came home drunk again and started beating Ra’no sister. Their neighbors barely managed to save her. Sevinch had grown tired of such fights. She wanted to leave that place far behind. So, after graduating from school, she applied to a university in a distant city.

The happiest news was that she was accepted with a full scholarship. Now, she would live in the city. Her parents came to see her off. For the first time in his life, her father embraced her and handed her a phone he had bought for her. Her mother, on the other hand, couldn’t stop crying. She didn’t want to part with a piece of her heart. But her daughter, her life, had to go.

Sevinch arrived in the city. As she was unpacking her belongings, she noticed a large sum of money. Her mother had given her all the money she had saved, sacrificing her own needs for her daughter.

Sevinch quickly adapted to city life. In fact, she even fell in love with a young man. He loved her deeply as well. One day, he proposed to her, and she said “yes.” Now, it was time for their families to meet.

Finally, the day arrived, but the young man’s mother opposed the marriage because Sevinch came from a poor family. Their family was wealthy and well-off. Hearing this, Sevinch stood up and left in tears. But her unfortunate mother couldn’t bear to see her daughter’s pain. She went to the young man’s mother, begged her, and even fell to her knees, pleading for their happiness. At last, the woman agreed to the marriage—but on one condition. Neither the girl’s father nor mother should ever bother them, and they must not even attend the wedding. Left with no choice, the mother accepted the condition—for the sake of her daughter’s happiness. Not long after, the young couple’s wedding took place. Keeping her promise, Ra’no sister never disturbed them. But is there any greater pain for a mother than being separated from her child?

Unfortunately, her suffering did not end there—it only deepened. Her husband passed away. True, he had not been a good man, but he was still her companion in life. Breaking her promise, Ra’no opa called her daughter and told her that her father had died. Sevinch rushed to the funeral, but she felt neither love nor sorrow for him. The reason was simple: Asror bro had never been a father to her. He had never given her love. Less than a year later, Ra’no sister’s joy—her only child, Sevinch—was diagnosed with a terminal illness and was admitted to the hospital. She had only one month left to live. Ra’no sister set off for the city to see her daughter, crying endlessly, nearly losing her mind. On the way, she thought about life… and why this world is always missing something.

Call for submissions (in any language)

La Federación Global de Liderazgo y Alta Inteligencia Federación Global Liderazgo Y Alta Inteligencia te invita a participar en la Antología poética para el día de las madres : Madre, mujer y templo.

Cada uno participará en su lengua madre. Adjuntar carta de autorización de uso. Este es un proyecto académico. Se solicita poesía a dos cuartillas en formato libre. Semblanza de 50 palabras y fotografía. Adjuntar video leyendo su poema para subir a televisión digital , YouTube y plataforma de Facebook en Cabina 11 Cadena Global Escríbeme en privado para más detalles.

Deadline 20 de abril del 2025.

Cuota de participación 20 dólares americanos . Paypal : mexicanosenred@gmail.com

Se entregara certificado de participación . Y su vídeo se integrara al material audiovisual de la presentación del libro.

La obra estará disponible en la plataforma de Amazon.

DrA Jeanette Eureka Tiburcio

Ceo

Global federation of leadership and high intelligence

Mexico

Send your poems

Will be broadcast in

Satellite TV channel

Certificate will be issued

Send with your poems

Letter of consent that you accept your poems to get published in Amazon

Fees 20$

DrA Jeanette Eureka Tiburcio

Ceo

Global federation of leadership and high intelligence

Editor Mundial

Stockholm project 2033

Spectator Sport

Been watching from a distance

For a while now. Life does that

To us, makes us spectators

Assigns us back-row seats and

Just leaves us there. There I go

Again restating the obvious, just

Holding it up to look at again, as

If I hadn’t been paying attention.

I like to say “us.” I like to say “we.”

But I don’t really know if I’m here

Alone or with others, the us and we.

The show has been going on for

Quite some time. The players all

Know their parts. The curtains open

And close. The theme music for all

This keeps playing. The audience

If there is one beyond me is getting

Restless. How many more times?

How long does this go on? When

Will the house lights come on, and

I get to finally walk away?

Stopping

A stop sign, another piece of our day

A pause on our way getting there or

Getting back from wherever we were.

I like to stop as if I am on a timer, just

A second or two when I’m the only one

In line. I like to come to a complete stop

Like someone fresh from drivers’ ed, stop

Then go, a prescribed measure. I stop to

See if someone is crossing in the cross

Walk just then or a car’s going through or

Turning. If they are I feel that the purpose

For the sign has been served. There are

Reasons for things. Things are put in our

Way because sometimes we need to be

Reminded that other folks are coming or

Going too. We need to be reminded to stop

And admit to our place in things. We are

Just another car filling space, rolling or

Racing on, turning, timing getting where

We are going in a group of others doing

Exactly the same damn thing.

Of Course

The inevitable is sitting mid-desk

Lined up properly, as you would

Expect. An envelope with a letter

To the effect that the inevitable has

Come this way. At least it’s not

An email or one of those meetings

That was obviously put together at

The last minute, with all your co-

Workers elbow to elbow knowing

That the Inevitable has finally come

To you/to them. You wonder at this

Difference, a letter left conspicuously

Mid-desk top, waiting to tell you what

You know it will. They even spelled

Your name wrong, the way they do so

Often. The misspelling was a joke for

So long, but now it just adds insult to

Injury. You think about waiting to open

The inevitable later, after you’re home

Or sitting in Patty’s, three sheets to

The wind. But no, you’ll open it now.

This is private and immediate. You’ll have

To face alone like this, alone like this.