302- Fernando Passoa Modern Dance Studio. Do you pony. Like hony maroni. Night of a thousand dancers. Rumba. Tango. vodka and orange premix cocktails. Worst drunk ever. The Beauty of the Husband: A Fictional Essay in 29 Tangos. Dance script with electric ballerinas. Not PK Dick. Fulton. Not the NY gov. Alice. Not the one who descends into rabbit holes. Of disinformation. 303- The Madwoman in the Attic. Jane Eyre or Wide Sargasso Sea. Jean Rhys or Charlotte Bronte. The one who actually got laid. Dominica or Haworth. Don’t drink the water. Hochmeister. Corpse water. The Blue Hour. After Leaving Mr. McKenzie. Good Morning Midnight. Voyage in the Dark. Smile Please. Difficult women. The end of the novel of love. Tigers were better looking. 304- Talking to frogs in boiling water. Lobsters on a leash. Sunday in the Park with. George. William or Mary. Who’s your Dada. 305- Now out of the blue, out of the black, a number caller-id’d from Hades.” Stephen Bett. Not the exchange. Rate. That’s bothersome. The caller id. What’s your area. Code. Zip. Code. Bar. Code. Navajo code talker anonymous. The answer (s), my friend, are blowing in the wind. 306- “Modern historical reality has greatly enlarged the imagination of disaster.” Said Susan Sontag. All too accurately. The beginning of the end. Them! The Hulk. Spiderman. Radioactive spiders from Mars. The Atomic Cafe. The sheep look up. Not Biblical. Though it could be. Was. Is. Not science fiction. Fallout. Illness as metaphor.

Poetry from Laszlo Aranyi

Art (Tarot, Major Arcana XIV.) The declining age first tastes like honey, yet its instant fermenting sweat, the constant human struggle, the cramped and inflexible exercise of power squeezes stinking secretion through the pore billions of Earth’s skins. The degenerate species are dying out. The Savior is climbing on the lustfully gaping chimney of the caves towards our Earth mother’s womb. The universe: an umbrella. Successive events: sewing machine. The creative intention: dissection table. What it’ll find is Cybele’s frog-headed, rotten fetuses, their tales are arrowhead claws (We lifted the processes of the dead world to the vegetative level, and indeed, fat homunculus jumped out of the alchemist's cauldron, but at a lower quality, as its creator.) The offspring are our caricatures! The offspring are our caricatures! The eternal mystery is research, experiment, when Aethyr collapses into a magical orgasm, and explodes. The remains are a cooled off, lifeless cosmic spider web, what for a moment, the charlatan enchanted to live. (Translated by Gabor Gyukics) Laszlo Aranyi (Frater Azmon)

A Művészet (Tarot, Nagy Arkánum XIV.) Hanyatló kor először mézízű, ám azonnal erjedő verítéke… Az állandósult emberi erőlködés, a görcsös és rugalmatlan hatalomgyakorlás bűzös váladékot présel ki a Föld-bőr pórus-milliárdjain. Kiveszőfélben a korcs faj. A Megmentő barlangok kéjre táguló kürtőjén mászik Földanyánk méhe felé. Az univerzum: esernyő. Az események egymásutánja: varrógép. A teremtő szándék: boncasztal. Amit talál: Kübelé békafejű, rothadó magzatai, farkuk nyílhegy-karom. (A holt világ folyamatait emeltük vegetatív síkra, s tényleg, kövér homunculus ugrott ki az alkimista-üstből, de alacsonyabb rendű minőség, mint teremtője.) Az utódok: karikatúráink! Az utódok: karikatúráink! Csakis a kutatás, a kísérlet az örök misztérium, amikor az Aethyr mágikus orgazmusba ájul, és szétrobban. A maradvány kihűlt, élet nélküli kozmikus pókháló, amit a szemfényvesztő egy pillanatra élővé bűvölt. Aranyi László

Laszlo Aranyi (Frater Azmon) The One Who Arrives Late Leaves the Earliest Ghost figure. Stretching and dilating erratically. It’s a cotton candy textured. wobbling flame of a candle. Its puke tasting flesh is sticky. Its silvery spark disappears in the depressing whiteness. “Whaddaya want, dickhead?” The Philosophers' Stone! The universal knowledge that transcends the worlds! Gopher chewed, holed, spray-stained hat on the scarecrow… Worthless… Our depraved World soon will be nothing else but a shrunken head pendant on the keyring of the Guardian of the Keys. Why do you always have to stir up the sediment? Miserable, despicable restrictors and restricted ones! A distrustful, fat cat is sitting on the threshold. (It is a Threshold…) The woman is again endlessly screaming without taking a breath. She’s drunk. She peed herself so ‘cause she wasn’t able to take her panties off in the toilet… She turned out from the forge, eerie amount of waste stir and move insidiously. A bunch of passersby are slim sandglasses demanding usurers. (Translated by Gabor Gyukics)

A késve érkező korábban távozik Szellemalak. Szeszélyesen nyúlik-tágul. Imbolygó gyertyaláng. Vattacukor állagú. Émelyítő ízű húsa ragadós. Ezüstös csillogása a elvész a nyomasztó fehérségben. „Mit akarsz, fatökű?” A Bölcsek Kövét! Az univezális, világokon átívelő tudást! „Pocok-rágásoktól lyuggatott, permetlé-foltos kalap a madárijesztőn… Nem jó az semmire… Az elfajult Föld előbb-utóbb úgyis zsugorított fejű figyegő marad a Kulcsok Őrzőjének kulcstartóján. Miért kavarjátok fel mindig az ülepedőt? Nyomorult, hitvány korlátozók és korlátozottak!” A küszöbön gyanakvó, kövér macska ül. (Ő a Küszöb…) Az asszony már megint egyfolytában, levegővétel nélkül rikácsol. Részeg. Még a bugyijától sem szabadult meg a WC-n, így összpisálta magát… Héphaisztosz műhelyéből került ki, alattomosan mocorog-mozdul a hátborzongató mennyiségű selejt. Uzsorást sürgető karcsú homokórák az összeverődött járókelők. Aranyi László

Essay from Jeff Rasley

An Experience of Wounded Knee

Goshen Redskins and Peace Times

The population of North American indigenous people was decimated by a 90 percent reduction and the land they controlled was reduced from 100 percent to 2 percent, as a result of the Anglo-European invasion and US conquest. The entire USA has and continues to benefit from the inhumane treatment of the people of the Native Nations.

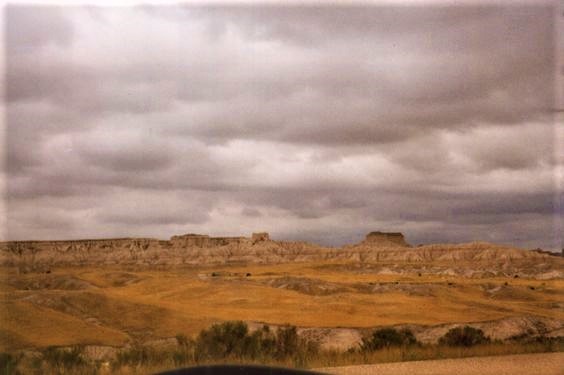

It is shocking and dispiriting to see first hand the land the US government “gave” the tribes of the Sioux Nation for their reservations in the Badlands, after Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse surrendered to end the Black Hills War. The Sioux didn’t even get all of the land, because the government cut out a major chunk of the Badlands to create Badlands National Memorial in 1929. Ten years later the memorial was upgraded to become a national park.

Driving across the bleak, prairie land of the Badlands, you pass forbidding white spires, angry grey cliffs, and squatty buttes. The Sioux people must have felt as desolate as the landscape, when they realized that, of all the lands they had roamed, the most uninhabitable area was where they were to be confined. The oppressive August heat in 2013 emphasized the grim harshness of the sun-baked landscape of the Badlands as I motored along State Road 40.

Evidence of neglect of reservation lands, and the needs of resident Indians, was even revealed in the road conditions to and through the Pine Ridge Reservation. South Dakota’s State Road 40, the road I drove heading southeast from the City of Keystone to the Pine Ridge Reservation, was a well-maintained, paved road. But when it became a Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) road within the reservation, the pavement ended. My vehicle had to endure forty miles of gravel whacking its undercarriage to reach Wounded Knee. Pavement reappeared when I left the reservation.

I stopped at Badlands National Park before driving through Pine Ridge to Wounded Knee. After reviewing the historical and geographical information at the Park Visitors Center, I asked the sole ranger on duty what I would find at the actual site of Wounded Knee. The ranger was tall, lanky, and had the weather-beaten good-looks of Gary Cooper. His laconic reply to my question was, “There’s not much there.” His answer was correct on the surface, but at a deeper, personal level, he was wrong.

On the east side of the dirt road at the site of the massacre were a couple of forlorn-looking booths with beaded belts, necklaces, and other handcrafts for sale. An elderly Indian in a stained white t-shirt with a Fruehauf Truck cap shading his eyes was asleep on a metal folding-chair behind one booth. A couple kids played in the dirt under the other table. On the west side of the road was a curved structure of wood and concrete with a sign indicating it was the American Indian Movement Center.

Inside, the walls were covered with posters and propaganda for AIM. The sparsely furnished interior had a long counter with an aged metal cash register. Piles of t-shirts, books, and handmade trinkets were for sale on top of rickety tables. The “library” consisted of several boxes of cut-out newspaper and magazine articles, a few dusty hardback books, and a scrapbook about the history of AIM.

Behind the building were two small hillocks with graveyards on top of each mound. An elderly Indian wearing a faded cowboy hat, dirty jeans, and stained t-shirt was leaning against the side of the building smoking a hand-rolled cigarette. I asked him if there was a monument to those who were killed at Wounded Knee by the US Cavalry. He looked me up and down without registering any expression. He slowly raised his arm and pointed toward a fenced area beyond a number of grave markers on the closest mound. I thanked him. He made no reply.

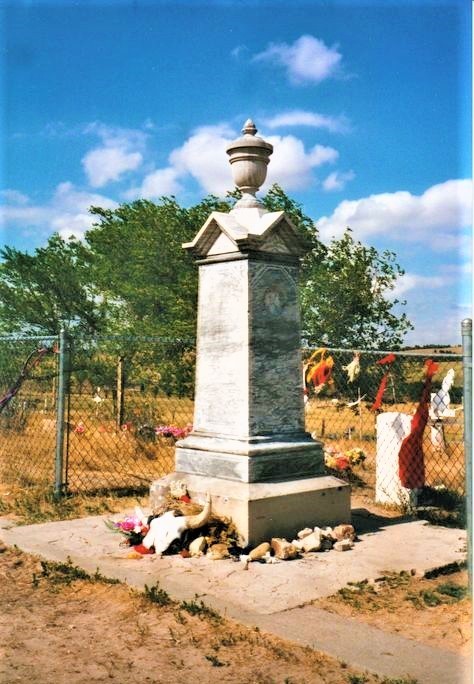

The fenced area for the memorial was about ten feet by six feet. A six-foot high granite monument stood inside the fenced area. Names of victims and a few words about the massacre were incised on the monument.

While we know that at least 200 – and it was probably closer to 300 of the 350 Minneconjou Sioux in Spotted Elk’s band – were killed at Wounded Knee, I counted fewer than 40 names on the monument. I don’t know whether the other names are lost in the mists of history. The skull of a horned steer was placed at the base of the monument. Shards of broken pottery, a few faded flowers, ribbons, and a couple fake gold coins were scattered around the base of the monument.

I placed two stones on top of the weather-beaten skull. I had purchased the rocks for one dollar each from two Oglala Sioux kids at the intersection of two gravel roads within the Pine Ridge Reservation. Their father told me he wanted to “encourage entrepreneurship” in his kids. Beaming with pride, Dad explained how his two boys search for nicely-shaped rocks, polish the best ones they find, and then sell the shiny stones on the roadside to people driving through the reservation.

How brave and pathetic! My heart ached for those kids and their dad.

It seemed like an appropriate symbolic gesture to pay for those two little pieces of the land and then give the polished stones back by leaving them at the memorial to Spotted Elk and the Minneconjou who were killed by the bullets fired by my ancestor, First Lieutenant James DeFrees Mann, and the soldiers of the 7th US Cavalry.

No one else entered the small cemetery during the half hour I spent on the hillock meditatively eyeing other grave markers. I shielded my eyes from the sun and gazed back across the road beyond the AIM Center. It was just over there, on the other side of the road, where Spotted Elk and his band of 350 Minneconjou Sioux had camped under the watchful eyes of Lt. Mann and the cavalrymen of K Troop. Beneath the soil of the earthen mound where I stood are the bones of the men, women, and children, whose bodies were tossed into the mass grave dug in the days following the massacre. The remains of more recently deceased residents of Pine Ridge Reservation share that little plot of raised earth with Spotted Elk and his Minneconjou.

Back inside the AIM Center, I tried to make conversation with a stoic-looking middle-aged woman, who was sitting behind the counter with a few kids. She didn’t give her name, and I didn’t ask. No other visitors entered the building while I was there.

I overcame my hesitation and told her about my ancestor’s participation in the Wounded Knee massacre. She evinced no hostility; just gazed evenly at me through tired brown eyes. She wore a blue work shirt buttoned up the front, jeans, and had long, straight black hair, which almost reached her waist.

She said she didn’t know anything about the cavalrymen involved in the massacre, and didn’t recognize Lt. Mann’s name. My look of surprise registered with her. She looked away, then pursed her lips and said that maybe she remembered reading an old newspaper that mentioned Lieutenant Mann.

A boy, who looked to be about ten years-old, studied me with watchful, curious eyes, when I was perusing the library materials. Later, while I was conversing with the Center’s attendant, the lad listened intently to our conversation. When the conversation wound down, the woman nodded at the boy and told me he was her son. That seemed to be the cue he’d been waiting for, because he launched into an obviously prepared speech requesting a contribution to a fund for his baseball team. He held out a rumpled leaflet for me to read. His limpid, brown eyes shone with excited anticipation. I gave him a ten-dollar bill, tapped the brim of his baseball cap, and wished him and his team good luck. His mother’s lips turned up very slightly at the corners. It was almost a smile; the first and only indication of friendliness I received from his mother. Her son thanked me and shook my hand formally.

Before I left the AIM Center, I bought a t-shirt for twenty dollars with the American Indian Movement logo on the front and back. The logo was the figure of an Indian warrior with two feathers in his hair shaped to look like the two-fingered gesture of victory.

I fantasized time-traveling back to high school and wearing the AIM shirt to a basketball game. Our varsity teams were the Goshen Redskins. The mascot was a little White kid, whose cheeks were streaked with red “war paint”. During my K through 12 years in the Goshen Community Schools, “Little Chief” wore an elaborate buckskin outfit with a feathered-headdress. He led the basketball team onto the court for warm-up drills before the start of each home game. During warm-ups, Little Chief stood at mid-court with his arms crossed like a dignified Indian chief. The little White boys chosen to be Little Chief were always about the same age as this boy, who looked at me with wide-eyed curiosity when I entered the AIM Center and shook my hand before I left.

My junior year in in high school, a young woman fresh out of college was hired as our journalism teacher. Ms. Thomas allowed students to change the name of the school paper from The Tomahawk to The Goshen Peace Times. Instead of bland, rah-rah school-spirit articles, The Peace Times published anti-Vietnam War articles and reviews of rock music. It printed an editorial suggesting that the team name should be changed out of respect for Native Americans. The editorial was met with almost universal hostility. It was condemned by townspeople, faculty members, school administrators, and many students. No Indians had complained about our mascot being offensive, nor had any tribes demanded that the school change the name. It was outrageous blasphemy against our customs and traditions even to suggest such a thing!

Ms. Thomas was rebuked for allowing her student-journalists too much freedom of expression. The high school administration shut down The Peace Times after that outrageous editorial. The young, idealistic journalism teacher left town at the end of the school year. But a couple decades later, in 2016, the Goshen Community Schools Board decreed that the team name would be changed from Redskins to Redhawks.

The Goshen News

I left the AIM Center and drove into the “town” of Wounded Knee, which was just around a bend on the unpaved BIA Road 28. A rusted metal chair stood in the middle of the dirt road running down the center of town. Resting on the rusty chair was a hand-painted sign on poster board. It read, Drive Slow Stop Killing Our Children.

Wounded Knee had the depressed ramshackle look of other settlements I’d driven through on reservations in South Dakota. But it was the worst. It was and is a squalid, poverty-stricken settlement with dilapidated houses and rusting mobile homes. When I was there, trash littered the street. An old woman walked across the dusty road in front of my car. She looked at me through the car’s window without registering any emotion. Her eyes were dull and her movements listless.

The Census Bureau’s information on the town of Wounded Knee for 2018 reports a population of 456 with a median household income of $7,292, which has fallen, instead of rising, since I was there in 2013. Between 2017 and 2018, the population of Wounded Knee declined from 521 to 456. According to the Census Bureau, the poverty rate is 95.2%, and only eleven residents are employed. The median household income for the State of South Dakota in 2019 was $58,275, about 8.5 times higher than the median family income in Wounded Knee.

The median age reported for Wounded Knee is 21.6. In South Dakota it is over 40. Several Trip Advisor descriptions of tourist experiences at Wounded Knee and the Pine Ridge Reservation include complaints of being accosted by young men demanding money or trying to scam tourists. Not that I approve of scamming tourists, but what exactly are young people supposed to do in a community with a poverty rate of 95.2 percent?

If America is going to continue to claim it is a moral leader, the “city on a hill” and beacon to the rest of the world, we have to finally and fully face up to our genocidal history and national sin.

Excerpted from America’s Existential Crisis: Our Inherited Obligation to Native Nations by Jeff Rasley, Midsummer Books 2021, exclusively available on Amazon.

Synchronized Chaos June 2021: Observer and Observed

Welcome to June 2021’s issue of Synchronized Chaos. We extend care to the regions of the world where Covid still rages and hope for the world to become safe and healthy.

This month, our writers and artists are seeing and being seen, observing and being observed.

One of Robert Thomas’ pieces presents a narrator in a cafe who eavesdrops on others’ conversations, only to find someone else commenting on him at the end. Thomas’ other piece is a character sketch of someone who presents himself in very different ways based on the setting.

Z.I. Mahmud contributes the first installment of his thesis on Charles Dickens. He explores the symbolism and images of life, death and disease in Dickens’ work and makes a comparison to today’s fear of disease.

Zara Miller, author of young adult historical novel I Am Cecilia, also analyzes literature, pointing out that one-dimensional, less complex characters worked in Shakespeare’s plays because everyone has some people who only seem to play one role in their lives. Although we are all full three-dimensional human beings, we don’t fully experience the inner life of everyone around us, and Shakespeare’s work reflects that.

Meg Freer presents a travelogue from the Republic of Georgia where she visits sites from the country’s Stalinist past.

Christopher Bernard writes a more fanciful kind of travel story, and this month brings us the moment when the little boy traveler realizes that he’s going somewhere unexpected.

Abigail George observes her own past, reflecting further on a past relationship. J.J. Campbell also writes of the many times and ways romantic attachment can miss its mark. Jerry Durick’s poetic speakers also self-reflect, thinking on how they’re aging, running out of space, and never quite living up to their dreams.

Chimezie Ihekuna spotlights a screenplay version of his reflective memoir Experiences, sharing his early life in Nigeria with a facial deformity. Another piece of his praises the editor of this magazine 🙂

Jack Galmitz contributes some vignettes concerning how we relate to our world, how major events filter their way down to our consciousness.

Charlie Robert’s poetic speakers are immersed within one singular moment, unconscious of being observed. John Culp writes of the ecstasy of losing himself in the moment, dissolving his past and present into love and creativity.

Christine Tabaka writes of our search for our place: within our families, within our social groups, to each other and to ourselves. We want others to fully ‘see’ us and include us.

J.D. Nelson’s pieces play with form and style while Mark Young speculates on the evolution of word meanings and poetic structures.

Mahbub ponders the fragility of life and the beauty of nature amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Hongri Yuan and translator Yuanbing Zhang voyage again to a mystical kingdom of order and beauty in the sky while Andrew Cyril MacDonald reflects on passing eras of our lives and of human history.

Mickey Corrigan shines a glaring light on Jeffrey Epstein and others who abuse their money and powerful positions. Sheila Henry calls for the world’s police forces to show empathy for the communities they patrol and the people they arrest.

Fay Pappas, attorney and former editor of Brushing, the literary magazine of Rollins College (Winter Park, FL), reviews Michael Robinson’s latest poetry collection From Chains to Freedom, which examines the Black male experience in the urban U.S.

Please enjoy this issue.

Poetry from Christine Tabaka

The Importance of a Daughter She always wanted a girl – two boys later … I appeared. The man could not be a father, so, she raised us, worked, provided on her own. Sadness was our family name! Years between siblings parted any bonds. My brothers left before I was aware. Time passed / I began to understand - the importance of a daughter, as we traded places. I never had a daughter – at an early age a son was ripped from my mold in the early morning hours - a lost wailing soul. Circumstance did not allow more children. I was not prepared for such a role. One would be my lot. One would be enough. Regret flies by on wings of time. Although, now in old age - sometimes, I miss what I did not have – the silken ties of mother to daughter. I Am Where I Need to be Right Now I am here, where I need to be right now, lost among the pages of myself. Torn from the spine, story still intact, never wanting to leave the scene. Numbered, spaced, each chapter ignites. Paragraph upon paragraph amass. It takes years to open the cover of my dream, painted with soft wings and somber clouds. Invoking words to give birth to a brand-new day, wrapped in the wonder of invention. Writing through the night, an outburst of intent settles into the dust of dawn. I remain right where I am, never swaying, never retreating, until the narrative ends. I must fill my life with purpose, with beauty, and with pain. Sending out pieces of myself hoping for acceptance, receiving none. I am where I need to be right now, writing the final installment of my life. I Faded in Your Dream I hear bluebirds singing in my garden. I see summer dancing on a wing. Clouds aloft in the heavens as everything turns green. Fragrant meadows open up to reach for new found warmth. Hours stretch across the horizon lengthening with each day. You stand there before me like a ghost from some past life. Sunset rules the evening as you turn and walk away. Never believing that you were real. You were brilliance, I faded in your dream. Life is a Cliché We cannot avoid the obvious – life is a cliché, shedding follicles, one by one, upon the shoulders of time. Fear-stained pages write the history, that we refuse to believe – instead, we close our eyes. Damn you, how can you write like that/ where do your words come from? I want to taste the blood – that spills upon the hard dirt floor. Come, fly with me – high above all that does not exist. We can never understand a truth that lies to the past. My severed tongue cannot pronounce the dislocated words/thoughts. Clichés bounce around in my poisoned mind. When I slow down – I hear those noises, that reach out to the end of nowhere. You are never there. Why would you murder my last chance - to catch a falling star? I keep asking myself – where do I go from here? Clichés spill from my empty mind into my empty hands. There is nowhere left to hide. I am forever the words/already spoken. His Name was Depression Depression walks on shards of broken glass, across burning sand, never tipping his hat to the invisible oasis that hides beneath the palms. He stands upon shoulders of the lonely, heaving his heavy sigh. Solitary thoughts waft through an air so frosty, it crackles with each breath. He wallows in its own despair, while looking heavenwards, praying for ransom from his daily strife. Tap-dancing on a splintered stage, that resonates with applause. Applause for everyone else, but never for him, Dysphoria. All the while veiled behind a false smile, tight and forced with doubt. Following dead dreams across a charcoal sky. Point and counter point. Depression laughs at himself as he sinks deeper in hot sand. All he ever desired was to be loved and understood.

Ann Christine Tabaka was nominated for the 2017 Pushcart Prize in Poetry. She is the winner of Spillwords Press 2020 Publication of the Year, her bio is featured in the “Who’s Who of Emerging Writers 2020 and 2021,” published by Sweetycat Press. Chris has been internationally published. Her work has been translated into Sequoyah-Cherokee Syllabics, into French, and into Spanish. She is the author of 13 poetry books. She has been published micro-fiction anthologies and short story publications. Christine lives in Delaware, USA. She loves gardening and cooking.

Chris lives with her husband and four cats. Her most recent credits are: The American Writers Review, The Scribe Magazine, The Phoenix, Burningword Literary Journal, Muddy River Poetry Review, The Silver Blade, Silver Birch Press, Pomona Valley Review, Page & Spine, West Texas Literary Review, The Hungry Chimera, Sheila-Na-Gig, Foliate Oak Review, The McKinley Review, Fourth & Sycamore.*(a complete list of publications is available upon request)

Christopher Bernard’s short story The Ghost Trolley, chapters 1 and 2

The Ghost Trolley

By Christopher Bernard

Chapter 1. A Town and a Boy

The town was called Halloway. More than a century ago it was a fishing village, and the fishermen went out each morning for cod and menhaden and lobsters and the streets were full of shrieking children and the sour smells of the harbor. There were mysteries about its past: rumors about an eccentric old woman being burned alive in the town during the Salem witch trials. Another rumor had it that, a generation later, after he was killed in an ambush by the Puritans, the head of a rebellious Indian chieftain was stuck on a pole outside the town’s palisade and left there as a warning for any other ambitious young natives.

A pleasanter rumor was that Halloway had been the last stop on the underground railroad for slaves trying to escape to Canada before the Civil War. But like the other rumors, there was no certain evidence to prove it one way or the other.

Then the fishing failed and the town fell on hard times. Many businesses closed, much of the younger generation moved out, and the town gradually shrank into itself, like an old man. Over several decades the small harbor silted up.

Then the war struck. Even this remote place was traumatized with the country at large for four long years, tragic telegrams coming even to this small community, until, like a gigantic Roman candle, the war burned out. Once it was over, young couples living in the big cities were eager to forget the war’s privations, and, like many another quaint seaside place, the town was discovered and for a time became a fashionable resort for the summer, with a trolley service and new streets planned and sewer lines and new telephone posts riding out far into the surrounding countryside like threads from an enterprising spider’s web.

But those times were ever a roller-coaster ride: the state was hit by another economic slump, the summer trade petered out, and the town was once again forgotten; two motels shut down, unfinished houses crumbled away with no one to occupy them, and to top it off, the local pastor murdered his wife and ran away with the church funds. The new roads ended in the middle of the surrounding woods, and the sewer lines stayed empty and waterless, hollow and echoey to the young local boys who stuck in their heads to explore their mysterious, fusty darkness.

It had finally been almost forgotten when elderly New Englanders discovered the little forgotten town near the sea, filled with untouched architecture going back half a dozen generations: a sweet little place, they thought, to retire to (the darker historical rumors were effectively suppressed by the local chamber of commerce). One of the retirees, a mailman from Burlington, Vermont, posted on the internet photographs of the town in its autumn splendor, though locals knew the deepest beauty in the region always came in the depths of winter, when the sun was disappearing like molten bronze through the stark, leafless woodlands.

A computer worker in far away California saw the photographs and promised himself to visit the lovely town next time he was back east. And when he did, he found himself not only in a pocket of natural loveliness, but also in an oasis in time, where people kept up old “analog” traditions on the verge of vanishing from the rest of the twenty-first century—scrimshaw, sampler weaving, knitting bees, building matchstick sailboats inside old whisky bottles, writing the entire U.S. Constitution on a kernel of dry yellow corn . . .

And, since he could work offsite wherever he wanted to, he decided to stay. And started posting his own pictures.

His friends in high tech soon learned how happy he seemed to be, and how perfect the peace and quiet, far away from the rat race of commuting, bad traffic and punishingly high housing costs where they were trying, with mixed success, to make a living. And, naturally, they grew envious . . . So, over the next few years, late into the night, the dark streets became increasingly lit by prim New England house windows behind which diligent techies worked, coding, testing, recoding, retesting, sending ghostly communications all over the world from this place which could be anywhere and so, in a sense, was nowhere.

Halloway had an Episcopal church with a white spire pointing heavenward and a small library with statues of John and Abigail Adams out front. Regularly you could hear, in the distance, the clang-clang of one of the trolleys from the service built long ago during the resort’s glory days.

Hickories, oaks, sycamores lined the streets, and deer were often found standing in the early morning on the front lawns, sniffing the dawn air as if listening to a far off call.

One day a young computer game programmer and his wife (who sold fashions on the internet and had a passion for Russian writers) moved to the curious old New England town.

As techies, neither was tethered to an office, so they had taken a deep breath and decided to move away from the “tent city of billionaires” (as the young woman called San Francisco, where they had been sharing an apartment with six other techies for an egregiously high rent—and where “never in the next millennium” would they ever be able to buy a home). But where to go? Then they had seen the idyllic little New England town and its many pictures on Instagram.

It offered an ideal combination of rustic seclusion and the stimulation and conveniences of the digital age—Netflix, Amazon, Skype chats! They would be able to live and work there comfortably while paying off their astronomical student loans. And it appealed to the earnest romantics in them.

A year after they moved to Halloway, they had a child. They named him Peter Myshkin Stephenson, after the hero of a famous Russian novel.

He was a curious little boy—in both senses of the term (as his great Aunt Marguerite noted on one of her visits from the city a hundred miles to the south): an “odd creecher,” full of wonder at this peculiar planet he had fallen to as if from outer space, full of doubt at people’s glib responses to his questions about why things were done the curious way they were in this world, full of objections to many things that seemed to strike many people as reasonable but struck him as ridiculous, and full of what he considered stupendously great ideas, a number of which, rather notoriously, backfired, such as his invention of a self-administering bathtub for their cat Max, or the self-propelling slingshot that turned rather too quickly into a boomerang and almost knocked the inventor’s eye out, or his revenge on Chace Fusillade, the son of their wealthy neighbor, for Chace’s burning of Petey’s homework assignment about Paul Revere, which paradoxically made Chace one of Petey’s best friends but made their parents enemies for life.

“Is Peter a complete idiot? The boy is impossible!” his mother lamented to his father, adding accusingly, “And where did he get that orange hair? We’re all blond in our family!”

The father—a quick, irritable man with a beard as thick as a hedgerow, and who looked older than his years and often acted younger—would roll his eyes and twist his mouth and say nothing, or smirk to himself, which made his witty, willowy wife hopping mad when she caught him. (His attitude was, what was the point in even trying to answer questions like that? There was no conceivable app!)

But the mother could never leave unanswerable questions alone. And soon they would be in the middle of one of their rows, which were becoming harsher over the years, as they blamed each other for their unhappiness in the old town far from the world they had tried to escape but had brought with them like an invisible monkey on their back: they had expected too much from Halloway, and Halloway, through perhaps no fault of its own, had let them down.

The Stephensons, it seems, still believed in happiness, and they blamed each other for not finding it.

Petey, alone in his room, exploring something in his home-made lab—the wing of a late summer moth, a crystal of purple mineral he had found in the garden, the mysterious result of mixing unknown chemicals in his little glass retort—would overhear these exchanges, which would build in intensity until the whole house seemed to shake with their fury – even when that fury was silent – and then, feeling frightened and ashamed, the young boy would sneak to a distant corner of the house where he didn’t have to know what was happening.

This place was often the bathroom, and he would look at himself, with alarm and scorn, in the mirror. What he saw was a moonlike, pudgy face, with two questioning eyebrows above blinky eyes and a pug nose covered with freckles and a small chin and two large, shapeless ears.

Was he stupid? Was he ugly?

The mirror stared back at him silently. “Well, what do you think?” it seemed to ask.

So: was it maybe true that it was entirely his fault that his parents were fighting like two mad dogs?

Maybe he really was an idiot. They valued above all things cleverness, good grades, cunning. His father made a big deal about outsmarting his rivals in the company, and both parents loved to play verbal one-upmanship games, sparring over dinner until his father, who was always a little behind his mother in the quick, blunt verbal rejoinders department, grew red in the face.

Petey’s grades in school were not bad. But then everybody’s grades were not bad. Even a true, genuine dope (everybody agreed on this one) like Charley Dunkin didn’t get really bad grades—just not bad enough.

On the other hand, if Petey truly were an idiot, how would he possibly even know it? This was a conundrum that gave him much food for thought, until his brain ached.

And then there was the other question: why was his face so round? Neither his mother nor his father had a round face. Even his grandparents had high cheekbones and long faces, like horses.

And where had his orange hair come from? He used to be quite proud of it, it was unique, no one else he knew had orange hair—but now he hated it.

And he hated himself. The mirror didn’t lie: he was fat, and he was ugly, and he was stupid . . .

He had been a mistake. He was sure of it. (The other day he had overheard Kelly in homeroom whispering to Melissa that Gretchen had been a mistake. No wonder nobody liked Gretchen, Kelly had whispered! Even her parents had never wanted her!)

The more he thought about it, the more convinced he became. It explained everything. Why had he been born so soon after they arrived in Halloway? Had they perhaps moved here so they could hide him from their families, so they would never even know he existed? He had never even seen his grandparents, except on Skype, and he sometimes darkly suspected they were in fact CGI . . .

He grew quieter around the house, and started saving his pestering questions for his teachers at school, and his reveries for the privacy of his room at the end of the corridor off the dining room, where he had a bed and a desk and a bookcase and his stuffed toys (Andy, Lionel, Monkey, and Lucile) and his telescope and chemistry set and his laptop and his charger, and a window that overlooked the backyard with the swing set and a great casement of sky speckled and sandy with stars on a cloudless winter night for as far as the eye could see (like last night, after the snow stopped and the moon rose like a face brooding over a stark, white world), and a door he could shut, turning his room into a place where he could dream up entire universes, inventing any possibility, worlds on worlds upon worlds, far from all perplexities and shame . . .

Chapter 2. To Otherwise

The trolley turned the corner, clanking through the freezing predawn, and, with its single headlight blinding bright, glaring like the head in the raised hand of the headless horseman, directed straight out of the fog toward Petey where he had been waiting, alone and half-frozen, under the old flickering streetlight.

It was a brand new trolley he had never seen before, shiny as if it had just been washed, which was of course impossible in this cold, or it would have been covered with a film of ice, and with a new route number and destination Petey had never seen before displayed above the windshield.

The bell clanged twice. The trolley squealed and groaned on the rails gleaming with ice and snow melt. There was no other traffic on the street and the night was pitch dark just before dawn.

The new trolley was painted bright yellow, and the new route number and destination appeared above the windshield in glowing capitals: “2 OTHERWISE.”

Petey had never heard of any place with the weird name of “Otherwise” – huh! It must be out near the ocean, or far in the other direction, where the old unfinished roads died out and the woods began. Someday, he would go to the end of the line and find out. But there was no time to do anything like exploring right now.

He hugged himself, his breath steaming in a shapeless white cloud in front of his face, and frowned ruefully. He has been waiting here for almost half an hour. Why was it so late? He mustn’t be late for school – not today!

The front, like that of most of the trolleys, looked very much like a face that was trying to hide a joke and doing a poor job of it.

Petey jumped in and clambered up the steps as soon as the trolley stopped. He asked the driver, who he could barely see where he sat in the dark cabin, whether this trolley went past his school.

“Yes, young man,” said the driver’s voice. “It does.”

Not entirely convinced, Petey slipped a school token into the coin box, trudged to a seat near the back and sat himself down.

There was no one on the trolley he knew, so he sat by himself and stared glumly out the window.

He had been late too often recently, so much that he’d been threatened with suspension if it ever happened again.

It was unfair; it wasn’t as though he was lazy. He’d had good reasons for being late. Once it had been because his mother had overslept after a particularly nasty late night quarrel with his father. Another time it had been because he’d had to make his own breakfast and prepare his own lunch. And the last time it had been because the cat had run away after the failed bathing invention and he’d gone looking for it. They never did find Max. He never came home again.

Now school was threatening him with suspension. He’d been suspended once, for breaking the principal’s window with a paintball gun while playing with Chace Fusillade. It had been an accident, he hadn’t meant it. But his father had beaten his bottom with a broken surge protector when he got home that night, shouting at him to “apologize! Apologize! Otherwise I’ll . . . !” And maybe for that very reason, he had clammed up.

When he was grown up, he sometimes thought, he would run away. Then they’d see. . . .

He listened to the trolley as it moved over the rails, seeming to say, in endless repetition, “Apo-lo-gize, apo-lo-gize, apo-lo-gize, oth-er-wise . . . ” and stared sleepily up at the winter sky.

It was a blue so dark it was almost black above the snowy ground, with the stars going out one after another like distant candles in a huge cathedral (he had been inside a cathedral once, in New York City), and there was a pasty pallor just above the horizon where the sun would soon be rising, and he felt his eyelids grow heavier and heavier as the trolley clanked in a lulling rhythm on the tracks. The sky just before dawn always seemed to be beckoning . . . “Must-not-be-late-for-school, must-not-be-late-for-school,” the tracks seemed now to be saying, over and over, “must-not-be-. . .” He felt his eyes becoming heavier and heavier. Whatever he did . . . he must not . . . miss . . . his school . . . stop. . . .

Soon he was fast asleep.

“Otherwise!” the trolley driver suddenly called out. “Last stop!”

Petey started awake—Oh no!—and rushed to the open door.

He halted.

If he got out now, how long would it take him to get the next trolley back?

On the other hand, if he just stayed on this trolley, it would have to go back eventually – wouldn’t it?

He looked around him. There was nobody in the trolley car but himself and the driver.

Suddenly the door closed.

Overcome with despair, the boy returned and plopped back down in his seat and stared into the blackness outside, imagining the principal’s face twisted in wrath as she suspended him and the reaction of his angry and “disappointed” (that awful word saved for only the most unforgivable humiliations) parents.

After a small torturous eternity that was in fact only ten minutes as the driver took his break, the trolley jolted awake and started moving again.

But something strange happened: instead of turning around, it continued going straight ahead.

The boy felt a little spike of panic, craning his neck toward the driver, though all he could see was the tall back of the seat inside the little cabin, and a jacket swinging from side to side on a hook near the front door. Then he turned back to the window and the darkness outside. He would never make it to school on time.

Then something happened to him. Oddly, now that there was nothing whatever he could do about being late for school (the sound of the trolley’s wheels on the track seemed to say, over and over again, “nothing you can do about it, nothing you can do about it”), the despair collapsed over him like a great wave and almost immediately washed away, leaving behind it the strangest tingling feeling – a curious combination of helplessness and a feeling of resignation, a sense of irresponsibility, and a peculiar feeling that he recognized, after a moment, was—yes!—relief.

He even felt a little thrill.

What would happen next?

Where were they going?

What would he find there, in this place with the strange name “Otherwise”?

And the yellow trolley carried him ahead into the darkness.

Fay Pappas reviews Michael Robinson’s poetry collection From Chains to Freedom

“From Chains to Freedom: A Journey of Freedom for the Black Male” is a quintessential example of Michael’s singular ability to distill his most private emotions onto paper in a way that instantly draws the reader into his shoes. In a recent interview with NPR, film director Barry Jenkins noted the potential for movies to become “empathy machines”; mechanisms by which total strangers are effortlessly pulled into the lives of others with very difference experiences than their own. To Michael J. Robinson, poetry is his “empathy machine”.

Take for instance, “Being Black”. There, he dives the reader straight into a world of sorrow, paranoia and pain (all based in reality and the poet’s own personal experiences) before yanking the reader back out of a bleak depth like a fish reeled from the ocean when “he remembers his mother’s kiss.” The line “He sees himself as others don’t” stands out as a note of defiance in this weary world.

“From Chains to Freedom” is not a comfortable read. “Comfort” is not the point. Removing the readers from their comfort zone is. Yet for all Michael J. Robinson’s description of a struggle shared by far too many and perpetuated far too long, the poet concludes on a remarkably hopeful note. Indeed, my favorite line out of the entire work comes from the second to last piece, titled “Some Place Special”: “There is a place where the sun speaks to the moon”. It’s this beauty amongst the pain, sorrow and death that would be dizzying or worse, exploitative, in less adept hands. But Michael J. Robinson doesn’t just know how to use his words, but he understands why he uses them.

I believe that makes all the difference because Michael’s ultimate message to his readers is that despite the pains of today, hope exists all around us should we heed it. Afterall, he reminds us, “there is a place where the sun speaks to the moon, while the mountains listen to the winds’ singing. Life is found in the trees as the sun whispers[…].

Fay Pappas is a practicing attorney and the former editor of Brushing, the literary magazine of Rollins College (Winter Park, FL). From Chains to Freedom can be ordered directly from author Michael Robinson by emailing him at mjrobinson@rollins.edu