Regular contributor Bill Tope has launched a new literary magazine, Topiary, which is now accepting submissions! Please send short stories to billtopiary1950@gmail.com.

In March we will have a presence at the Association of Writing Programs conference in Baltimore which will include a free public offsite reading at Urban Reads on Friday, March 6th at 6 pm. All are welcome to attend!

So far the lineup for our reading, the Audible Browsing Experience, includes Elwin Cotman, Katrina Byrd, Terry Tierney, Terena Bell, Shakespeare Okuni, and our editor, Cristina Deptula. If there’s time, an open mic will follow.

Our next issue, Mid-March 2026, will come out Sunday March 22nd.

Yucheng Tao announces the winners of his poetry competition, Steve Schwei and Mark DuCharme. We’ve invited both winners to submit their poetry to Synchronized Chaos for everyone to read!

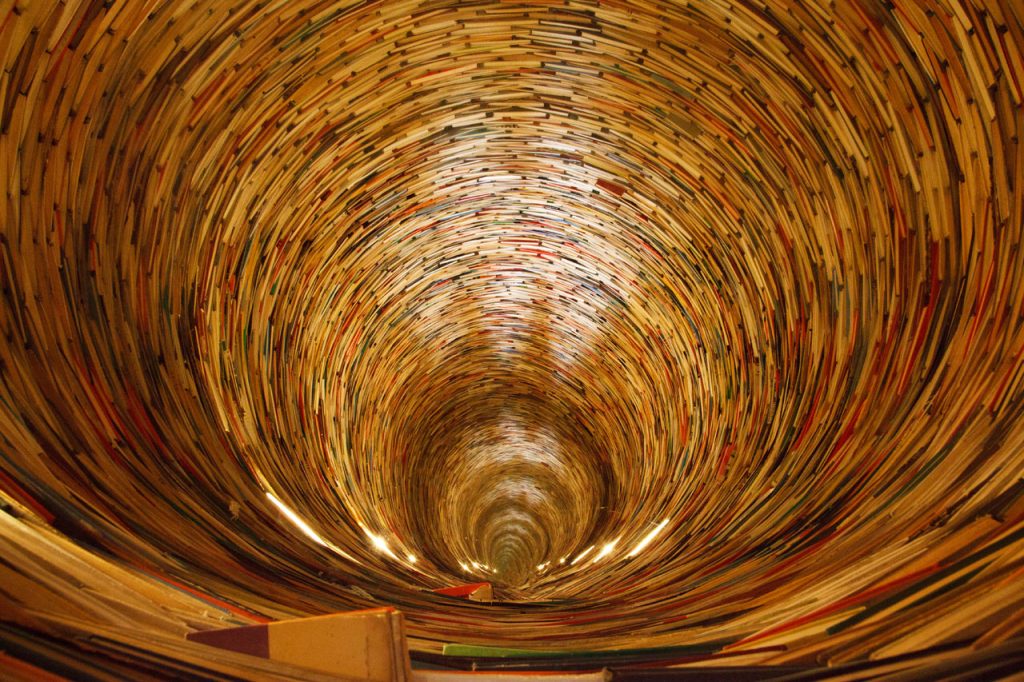

Now, for March’s first issue! This issue, Fingering the Spines, pays homage to our annual in-person reading, the Audible Browsing Experience. It’s a visual metaphor for looking through various titles in a global bookstore or library.

Genevieve Guevara rings in the dynamic energy of the Fire Horse for Chinese New Year.

Odiljonova Mohlaroyim Iqboljon qizi celebrates the many styles of Uzbek spoken word art. Umarova Gulsevar Ubaydullo qizi highlights the rich semantic and lexical expressiveness of the Uzbek language. Shuhratova Mohinur Abbosjon qizi explores the layered meaning of “k’o’ngil” (heart) in the Uzbek language.

Jesus Rafael Marcano celebrates the beauty of France, likening the nation to butterflies. Timothee Bordenave honors the beauty and majesty of Christian faith, as shown through Notre Dame. Su Yun’s abstract work reflects a meditative, spiritual sensibility. Soumen Roy describes a physical and mental journey towards spiritual inspiration.

Abdumajidova Zuhroxon Ibrohimjon qizi explores themes of hardship and endurance, destiny, faith, patriotism, and loyalty in Shuhrat’s classic Uzbek novel Oltin Zanglamas. Iroda Ibragimova explores themes of resilience and human dignity through oppression in Shukrullo’s novel Buried Without a Shroud. Bakhtiyorova Zakro Farkhod qizi speaks to the role of the short story in Uzbek literature. Ro’zimatova Madinaxon Sherzod qizi analyzes themes of strength, weakness and humanity in Abdulla Qahhor’s story “Ming bir jon.” Anvarova Mohira Sanjarbek qizi contributes a heartfelt poem from the perspective of Gulchehra, a character in O’lmas Umarbekov’s “Being Human is Hard.”

Azimov Mirsaid draws on Ray Bradbury and traditional Uzbek crafts and hospitality to illustrate the value of human warmth and imperfection. Dr. Jernail Singh Anand urges humanity to look into the words of our past and present writers and philosophers for wisdom in this age of great technological advancement. Dr. Jernail Singh Anand also expresses hope for the continuance of human creativity in the age of artificial intelligence. Daniela Chourio-Soto renders all-too-human morning sleepiness with lively humor. Eva Petropoulou Lianou explores the feelings and inspirations of emerging Greek painter Vivian Daouti.

Author Victoria Chukwuemeka discusses her creative journey towards exploring psychology and the subconscious, becoming deeper and more straightforward in her words. Kassandra Aguilera’s work mourns her speaker’s incompleteness, probing whether we need observers to fully realize ourselves. Ananya S. Guha reflects on distance, separation, and reunion, how roads can both bring us apart and together.

Emeniano Somoza poetically compares creative writing and glassblowing: arts where creators shape, rather than force, their materials. Poet Su Yun collects a set of poems from children at the East-West Public School in Bangalore on the theme of “the power of the pen vs the sword.” Taylor Dibbert’s short piece is almost anti-poetry, suggesting without communicating a metaphor.

Stephen Jarrell Williams’ poetry speaks to the risks and joys of openness to emotion and experience. Komilova Parizod reminds us to make the most of our lives and appreciate the joy around us. Priyanka Neogi urges us to act with wisdom and restraint. Boymirzayeva Dilrabo highlights the importance of motivation and discipline in reaching one’s goals.

Sobirova Oydinoy Nozimjon qizi discusses symptoms and types of neurosis. Mashhura Ochilova speaks with poignance and grace of a young woman’s inner battle with depression. Graciela Noemi Villaverde speaks to gaining wisdom through life’s losses. J.J. Campbell’s voice is older, raw, bruised, with hard-won exhaustion and experience.

Axmedova Gulchiroyxon expresses her tender love and concern for her mother. Nurmurodova Masrura Xurshedovna honors the patient, dedicated, behind-the-scenes love of her father. Gulsanam Sherzod qizi Suyarova explicates the value of friendship and how to be a good friend. Aminova Feruza Oktamjon kizi celebrates the beauty and innocence of young love. Qozoqboyeva Husnida yearns with devotion for her soulmate’s arrival. Mesfakus Salahin falls into a reverie about a fanciful love that exists between his imagination and his memory. Prasanna Kumar Dalai smiles through a delicate and tender love. Joeb expresses his hopes for personal and global love and peace. Lan Xin celebrates transcendent union with all others and the universe, with the world as her homeland, in her fanciful dinner piece. Husanxon Odilov laments a love which he acknowledges will never return. Nicholas Gunther reflects on a high school lost love or friendship through a casual ghazal. Bill Tope and Doug Hawley present an unusual relationship arrangement that seems to make several older people happy. Masharipova Yorqinoy Ravshanbek qizi celebrates the tenderness of a mother’s love. Brian Barbeito’s gentle childlike piece creates a surreal atmosphere rich in memory and care. Orzigul Sharobiddinova Ibragimova versifies her love and longing for her Uzbek homeland.

Zarifaxon Nozimjon Odilova qizi highlights the historical contributions of Uzbek statesman and humanist leader Zahriddin Muhammad Babur. Toshkentboyeva Xumora outlines the contributions of Amir Temur to modern Central Asian statecraft. Poet Lan Xin highlights the wisdom and compassion of Chinese Dongba cultural leader Wan Yilong. Abdusaidova Jasmina explicates themes of spirituality, heritage, and love in Alisher Navoiy’s writing. Abduxalilova Shoxsanamxon Azizbek qizi celebrates the benefits of reading culture for society.

Murodova Zarin Sherali qizi explicates the importance of language learning in world communication and international and intercultural relations. Khusanjonova Mukhtasarhkon Khamdamjon qizi discusses how podcasts can help those learning English as a foreign language. Turdimuradova Zulfera Sattor qizi analyzes the use of blended learning in teaching English as a foreign language. Suyunova Zuhra Oybekovna speaks to the importance of writing skills to language learning.

Olimova Marjona Ubaydullayevna celebrates the literary heritage of Zulfiya and her themes of patriotism, women’s dignity, and compassion. Munisa Yo’ldosheva highlights how Zulfiya’s life influenced her works and her contributions to supporting emerging authors. Nozigul Baxshilloyeva discusses emotional and spiritual themes within Zulfiya’s work and how they affect Uzbek readers. Sultonova Shahlo Baxtiyor qizi highlights the literary and cultural influence of Zulfiya’s poetry. Jurayeva Barchinoy does the same, while also highlighting her commitments to education and women’s rights. Nematullayeva Mukhlisa Sherali kizi relates the value of Zulfiya’s work through a narrative story. Gayratova Dilnavo highlights the enduring legacy of Zulfiya’s work, especially what it means for many Uzbek women.

Loki Nounou’s piece dramatizes a woman stripped of her individuality in a toxic marriage, becoming only a vessel to hold others’ dreams. Abigail George probes the maternal and domestic as both sacred and violent, an origin and a wound, along with critiques of colonialism and the power of self-kindness. Manik Chakraborty calls for a natural, spiritual feminine awakening. Asadullo Habibullayev warns of the dangers and social injustices young women can face in Uzbekistan, even when educated, and calls for the younger generation to respect the wisdom of their elders. Eva Petropoulou Lianou urges respect for women and for the roles women play in society, including motherhood. Maxmarajabova Durdona Ismat qizi celebrates the love and care of human mothers and the value of Mother Earth.

Zamira Moldiyeva Bahodirovna analyzes what the nature motifs in Alexander Feinberg’s work reveal about his thoughts on memory and identity. Noah Berlatsky draws on trees to illustrate our shared human heritage, how we connect to each other and hold each other up. Dilafruz Muhammadjonova presents a natural and cultural tour of Uzbekistan’s Andijan province. Suyunova Fotima Oybekovna reminds us of how crucial it is to preserve the environment. O’gabek Mardiyev outlines ways to improve the efficiency of solar power generation. Shavkatova Mohinabonu Oybek qizi urges improvements in Uzbek public transit to encourage tourism as well as benefit ecosystems. Sultonaliyeva Go’zaloy Ilhomjon qizi analyzes the social, cultural, ecological and economic aspects of tourism in Central Asia. Turgunov Jonpolat discusses the ways in which media framing of climate issues affects how people address the problem. Surayyo Nosirova highlights the need for more consistent communication from journalists to the public about climate change in Uzbekistan.

The works of primary school children in China, collected by Su Yun, reflect moments of happiness and ordinary summer fun in nature. Alan Patrick Traynor’s Irish-inspired piece becomes incantatory, mystical, inhabiting littoral and transitional zones at the ocean’s edge. Tea Russo’s spiderweb poem seeks both expansive transcendence and the peace of oblivion, melding into various aspects of nature. Turkan Ergor dreams of the permanence of the ocean’s waves. Eleanor Hill reflects on the calm strength and dignity of a whale, unbothered while creating waves and blowing bubbles. Ri Winters turns to the ocean and its kelp forests as metaphor for the deep, isolating, yet restful morass of depression.

Brian Barbeito sends up a preview of his book Of Love and Mourning, highlighting the original content and the memorials to beloved pets who have passed. Filmmaker Federico Wardal celebrates a film award for a very humane documentary about veterinary care that saved the life of a racehorse. Jerrice J. Baptiste’s piece, accompanied by gentle, colorful artwork, expresses a graceful and natural surrender to death. Sayani Mukherjee’s piece sits between devotion and restlessness, calling the sky a neighbor yet screaming at stars. Mykyta Ryzhykh crafts a fevered love elegy at the edge of war, eros, and annihilation.

Patrick Sweeney sends up a set of index cards from a memory archive. Mark Young’s altered geographies trace the outlines of innocence, memory, and rupture. John Grey’s urban character and landscape pieces show dry, unsentimental grace.

Duane Vorhees’ poetry meditates on time’s circularity, embracing contradictions and the past, present, and future. Ibrahim Honjo reflects that one day his home and everything he knows will fade into memory. Christopher Bernard continues exploring hope, ruin, and creative resilience in the second installment of his prose poem “Senor Despair.”

Maja Milojkovic speaks to the implacable ticking of conscience. Mahbub Alam laments the selfishness and wickedness of humanity. James Tian dramatizes the pain of being underestimated, dismissed, and misunderstood. Mark Lipman calls for greater taxes on the wealthy and for economic egalitarianism. Jacques Fleury hoists his commentary on the fragility of modern democracy on the scaffolding of an extended construction metaphor.

Rahmatullayeva Elmira Rahimjon qizi discusses how we form the value systems that guide our lives. Abduraufova Nilufar Khurshidjon qizi outlines the national values and traditions of the Uzbek people. Islomova Maxsudaxon Axrojon qizi explores ways to inculcate values into Uzbekistan’s young people in school through exposing them to the great thinkers of their heritage. Botirova Mubina looks into ways Uzbekistan’s civil society can uplift teens and prevent delinquency through communicating their national values. Abdullayeva Ezozaxon Qobuljon qizi highlights the importance of social and financial investment in education. Ismoilova Jasmina Shavkatjon qizi highlights the importance of quality education for social progress.

Axtamova Orastaxon Salimjon qizi outlines strategies to assist autistic children’s psychological development. Rajabova Nozima highlights methods of improving young students’ reading comprehension. Dildoraxon Turg’unboyeva outlines the effectiveness of play-based learning methods in education. Sevara Tolanboy Mahmudova qizi discusses educational games for preschoolers. Turgunboyeva Dilafruzxon highlights the importance of preschool education to a child’s development. Muxlisa Olimjon qizi Tursunaliyeva and Adhamova Irodaxon Akmal qizi discuss ways to help educate children with learning disabilities. Dilnora Habibullo qizi discusses interactive methods for teaching children with and without special needs. Burhonova Lobar outlines suggestions for working with children on the autism spectrum. Hikmatova Nigorakhon Hasanboy qizi discusses how to upgrade physical education and make the activities more interactive. Turg’unova O’g’iloy Ravshanbek qizi discusses ways to incorporate physical activity into children’s academic education. Shahobiddinova Sevinch explores the use of educational games in primary education. Arziqulova Adiba details various interactive strategies for engaging young children in educational activities at school. Mashhura Kamolova analyzes the limitations of examinations in terms of measuring student capabilities.

Orinboyeva Zarina discusses how to help children psychologically and emotionally navigate their parents’ divorce. Botiriva Odinaxon elevates the teaching profession and calls for professional development and competence in those who educate young children. Nishonboyeva Shahnoza speaks to her wisdom and dedication towards her goal of becoming a preschool teacher.

Kadirova Feruzakhan Abdiyaminova discusses interactive games that could be useful in science education. Oroqova Nargiza outlines the rise of allergies in children and speculates on the causes. Umidjon Hasamov highlights the potential for artificial intelligence in medical diagnostics. Yunusova Sarvigul Siroj qizi highlights the importance of early screening for gastrointestinal cancer. Rajapova Muqaddas Umidbek qizi highlights the structure and function of the circulatory system.

Shohnazarov Shohjaxon highlights the impact of inflation on a nation’s economy and strategies for managing it. Mamadaliyev Kamronbek highlights the need for cybersecurity technology and cautions about cyberattacks as a weapon of war.

Dr. Jernail S. Anand calls out poets and academics whose lofty ideas don’t connect to present-day reality. While we are all capable of flights of fancy, we hope that this issue is grounded in our world and our humanity.